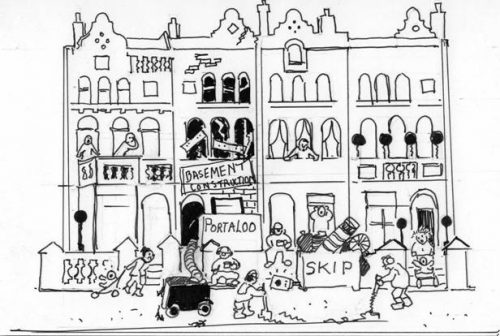

Keeping the Ladbroke area special

Report on a survey on the impact of subterranean development on neighbours in Kensington

Ladbroke Association

December 2009

INDEX

MAIN REPORT

Section 3: Noise and vibration

Section 5: Dirt, dust and rubbish

Section 8: Starting off on the right foot

Section 9: Party Wall Agreements

ANNEXES

C: Objectives of the Ladbroke Association

“Excessive noise, dust, vibration – we’re two years in and probably another 18 months to go.”

“Dust, dirt, vermin and noise 6 days a week for more than a year.”

“Noise was truly excessive. Our whole house was vibrating all day. It almost drove me mad.”

This is a report on a survey carried out in Spring 2009 of the impact on neighbours of subterranean developments in North Kensington. Out of the 200 or so questionnaires delivered to 95 properties 64 were returned completed – many in great detail. The Ladbroke Association decided to carry out this survey because, although there were many reports of residents enduring unacceptable intrusion into their lives and damage to their homes, there were very few facts.

There has been considerable research and endless discussion about the potential impact of subterranean developments on the structure of neighbouring houses and of the effect on ground and subsurface water. These aspects were looked at in depth in the Ove Arup Report commissioned by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, and RBKC subsequently issued a Supplementary Planning Document on Subterranean Development. The survey goes beyond these to provide evidence on what actually happened to neighbours and their property during the planning process, the actual construction and thereafter.

You will find in the report that some of these projects were planned and managed in an exemplary manner, but many were not and some had appalling results for neighbouring houses for many months or even years. If you want to see the worst sort of case, just visit Upper Phillimore Gardens now.

While we were writing the report it became apparent that, although we had dealt only with sites involving significant underground developments, a similar degree of disruption would also be encountered in many major refurbishments not involving subterranean work. In practice, therefore, most of our recommendations apply to all types of major residential refurbishment.

It might be argued that the survey highlights problems which occur only in areas of relatively high value houses. But building work can happen anywhere, and it seems to us likely that the changes that we are recommending will benefit residents living in any area of terraced or semi-detached housing unfortunate enough to find themselves living next to major building work.

Many of the recommendations that we make lie within the grasp of RBKC to implement. One of our principle recommendations is that the Council should devise a “Good Development Guide” similar to the code of practice issued by the City of London. Other recommendations would require legislative change to alter the balance of planning considerations so that, for example, a council could take into account the balance between the nuisance caused by the construction and the desirability of the development and that appropriate compensation for major nuisance be paid by developers of residential sites on a compulsory basis.

During the production of this report we have received valuable advice and support from many people, including officers in RBKC and other organizations such as the Kensington Society and various Conservation/Residents Associations in the Borough.

Copies of this report are being sent to all Councillors of RBKC and to local conservation/residents bodies in the Borough. In addition of course it will go to the various Departments in RBKC; and we will be sending copies to other London boroughs likely to face similar problems; to the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government; to the shadow Ministers of the other two parties; and to the local MP and MEPs. The whole report is available on www.ladbrokeassociation.org.uk, as is a summary of the responses received to the survey. Correspondence about the report should be addressed in the first instance to me at the address below.

On behalf of all those who have to live next to these developments for sometimes years on end, we urge both local and central government to take this report very seriously indeed.

David Corsellis

Chairman

Ladbroke Association

December 2009

1. The main problems caused by major underground developments in residential areas are the prolonged noise (way above normally acceptable levels), vibration, dirt and dust to which neighbours are subjected over prolonged periods (the survey showed that these developments normally take at least 18 months and sometimes as long as three or four years).

2. Although cases of extreme damage are rare, cracking to party walls and other minor damage to neighbouring property is almost inevitable from such developments.

3. In the longer term, there is a need to rethink the controls on the planning and execution of major building works in residential areas. In particular, given that construction projects in residential areas, such as underground developments, are so much longer and noisier than used to be the norm, changes to legislation should be considered in order to redress the balance between the desirability of allowing lengthy and noisy developments and the right of neighbours in residential areas to have a peaceful family life and reasonable enjoyment of their property.

4. In the meantime, although RBKC’s powers (and resources) are currently limited, there is a lot that can be achieved through guidance and the exertion of pressure. The City of London has produced an excellent “Code of Practice for Deconstruction and Construction Sites”. RBKC should do likewise and produce a detailed and wide-ranging “Good Development Guide” to supplement the Considerate Contractors Scheme. This should cover the whole process, from consulting neighbours in advance of seeking planning permission to ensuring that problems caused by the works are ratified quickly. The existence of such a Guide or Code should make it easier for the Council to take action against noisy and or dirty works under environmental legislation.

5. RBKC could improve its handling of both planning applications and subsequent building work for residential developments by the implementation of various actions contained in the Recommendations of this Report; for instance by requiring the Construction Methods Statements, which developers must produce when seeking planning permission, to address how noise, vibration, damage and dust will be minimised; and by better arrangements (such as an improved hotline) for dealing with problems as they arise.

6. It is impossible to avoid at least some noisy work, and given that this can make life intolerable and work impossible for those in neighbouring houses, there is a case for those undertaking such works (who usually move out while they are going on) to pay some compensation to neighbours for loss of amenity.

7. Many people probably do not make as good use of the Party Wall Award system as they might. The Ladbroke Association proposes to produce a Guidance Note based on the findings of this survey as to what clauses might be usefully included in Party Wall Agreements for potentially noisy and damaging residential developments.

8. It is not impossible that a case against noisy building works brought by an aggrieved neighbour might succeed under the general law of nuisance or under the Environmental Pollution Act 1990.

9. Whilst the survey covered only sites where subterranean developments were planned and took place, many of the problems that arise from these will apply just as much to major residential developments that do not include a subterranean element.

The recommendations below are grouped by subject and are not necessarily in any order of priority. The relevant paragraph numbers in the full report are shown in brackets.

1. Good Development Guide

RBKC, perhaps in conjunction with other London Boroughs similarly affected, should devise a voluntary Good Development Guide to supplement the Considerate Contractors Scheme (paragraph 3.16 and Annex B). This should include the following advice:

- Applicants should consult neighbours before putting in an application (paragraph 8.3).

- Planning applications should be comprehensible to the lay person without having to resort to obtaining specialist advice (paragraph 8.3).

- Developers should inform neighbours when works are beginning and how long they will last, and of any changes of plan (Annex B).

- Party Wall Agreements must be in place before the work starts (paragraph 9.2 and Annex B)

- Developers should consider arranging particularly noisy work at periods when it least incommodes neighbours, and leave periods of peace and quiet (paragraph 3.30).

- Builders should not play radios or other sound systems unless the neighbours agree (paragraph 3.2 and Annex B).

- Developers should clean up regularly and avoid dust, for instance by cutting stone and other materials off-site (paragraph 5.2 and Annex B).

- Rubbish should be regularly cleared to avoid vermin (paragraph 5.2 and Annex B).

- Lorries and skips should only be moved within standard working hours, and should always be parked within agreed areas (paragraph 6.5 and Annex B).

- Entrances and other access points belonging to neighbouring properties should not be blocked (paragraph 6.1 and Annex B).

- Contact details of a responsible site manager should be made available to neighbours in order to deal with any problems that cannot be sorted out by the builders working on the site (Annex B).

- Developers should make compensation payments for nuisance and for loss of use of gardens. The Council should work out a recommended model scale of payments that could be used in Party Wall Agreements (paragraphs 3.34, 5.3 and Annex B).

2. Other actions by the Council

RBKC could improve its handling of both planning applications and subsequent building work in residential developments by a number of other actions:

- The Council should require the Construction Methods Statement (CMS) at the application stage specifically to address at least in outline how noise, vibration and dust effects are to be dealt with (paragraph 3.21).

- The CMS should also include calculations to demonstrate that damage to adjacent buildings will not exceed the “very slight” category (paragraph 4.7).

- Deviation from the standards in the Construction Methods Statement could be the basis for enforcement action under S.60 of the Control of Pollution Act 1974 (paragraph 3.25).

- The Council could do more at the application stage to ensure that objectors understand both the planning system and the current limitations on the Council’s freedom of action with respect to underground developments (paragraph 8.5)

- The Council should include in planning permissions an Informative about the need for a Party Wall Agreement to be in place before work starts (paragraph 9.2)

- The Council should develop, perhaps with the help of outside experts, guidelines on acceptable noise levels (paragraph 3.25).

- Arrangements for hotlines to handle calls or emails relating to ongoing building works should be improved and a follow-up system established to track whether appropriate action has been taken in response to calls or emails (paragraphs 7.3 and 6.5).

- Greater restrictions should be put on the use of skips in narrow streets or where parking is difficult; instead the requirement should be for debris to be bagged up and removed by lorry (paragraph 6.5)

- The length of parking suspensions for building works should be minimised and renewals should cost more (paragraph 6.5)

3. Party Wall Agreements

The Ladbroke Association should produce a guidance note based on the findings of the Survey containing clauses might be usefully contained in a Party Wall Agreement (PWA) (paragraph 9.4). This would complement the proposed Good Development Guide to the extent that several of the items in the latter could be enforced through inclusion in the PWA. Elements that could be included as standard in the Party Wall Agreement include:

- A sum of money to be lodged in an account kept by the Party Wall Surveyors to cover the cost of putting right any damage caused, so as to avoid problems caused by developers going out of business (paragraph 4.4).

- Neighbours should be a named party on the builder’s insurance policy (paragraph 9.3).

- Appropriate arrangements to ensure the security of the neighbour’s house during the construction, eg alarming scaffolding.

- Defects such as doors and windows out of alignment because of movement in neighbouring structures should be rectified immediately at the developers’ expense (paragraph 4.3).

- If burglar alarms are set off by vibration from the works, the developer should bear the call-out and other associated costs.

- Arrangements for compensation for loss of use of gardens and for other nuisance (paragraphs 3.34 and 5.3).

4. Legislative changes

In the longer term, there should be changes to legislation to:

- provide for appropriate compensation being paid by developers on a compulsory basis in mitigation for nuisance (paragraphs 3.32 and 3.33).

- allow Councils be allowed to refuse planning permission where approved noise standards cannot be met (paragraph 3.5).

- allow Councils to take into account the balance between the nuisance caused by construction in residential areas and the desirability of the development (paragraph 3.6).

- allow Councils to withhold or delay planning permission to ensure a decent interval between noisy developments in the same area (paragraph 3.7).

- implement existing unimplemented legislation on fees to allow Councils to set their own planning fees to take account of costs such the employment of independent experts (paragraph 3.22).

5. Bringing a case under environmental legislation

The Report notes that it is not impossible that an aggrieved owner could successfully pursue a case against noisy building works under the general law of nuisance or under the Environmental Pollution Act 1990. This would, however, require the neighbour to undertake detailed monitoring of noise levels etc and careful collection of evidence (paragraphs 3.13 and 3.14).

6. Major damage

The Report notes that, while major structural damage from underground developments has hitherto been rare, the survey brought to light four worrying cases. RBKC should ask an independent Chartered Structural Engineer to investigate these cases to see if there are any lessons to be learnt (paragraph 4.2).

MAIN REPORT

1.1. In the past few years the Committee of the Ladbroke Association, which is the conservation society for the Ladbroke Estate, has become increasingly conscious of the noise, dirt and structural damage (actual or potential) caused by subterranean developments under houses, gardens and forecourts in the Victorian terraces of the area. Although the Committee of the Association opposed many such developments at the planning stage, it has had to accept that, provided the application is properly produced, planning approval is likely to be given by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC). But the Association felt quite strongly that ways should be found of mitigating the problems caused by major underground developments. One of the difficulties was that the evidence of problems tended to be anecdotal. The Committee therefore decided to instigate a survey of the impact of such developments on neighbours.

1.2. The survey was to cover experiences during the planning process, the actual building works and the aftermath. In order to provide a large enough sample, it was decided to cover such developments in a wider area than the Ladbroke Estate. RBKC provided a list of all approved applications for some form of subterranean development in the Borough since 2002 – about 600 sites. From this list we selected 95 sites in the five northern wards, Campden, Colville, Holland, Norland and Pembridge, at which the proposed development appeared to us to be likely to have a significant impact on neighbours. We had no information as to whether the proposed development had actually started or taken place.

1.3. In late February 2009 a questionnaire and covering letter (at Appendix B) was delivered by hand to the houses on either side of the proposed development sites and in some cases also to the houses opposite. Copies were also sent to the Councillors of the wards concerned. 64 replies concerning 49 of the properties selected were received. Of these 49 properties, at nine the work had either not taken place or had not yet started and at 15 work was still ongoing – in several cases more than 2 years after it started.

1.4. The completed questionnaires were in many cases very detailed and processing them has taken the Committee quite some time. A preliminary factual report on the survey was included in the Association’s newsletter, published in May 2009.

SECTION 2: RESULTS OF THE SURVEY

2.1. The main concern that emerged from the survey was the appalling noise and vibration that was inflicted on neighbouring houses over long periods during the construction. This was closely followed by concern over dirt and dust and traffic problems. There were only a few cases of major structural damage to neighbouring houses, but a worrying incidence of minor damage and problems enforcing Party Wall Awards. There was also a strong feeling that not enough was done to consult neighbours in advance of these developments proceeding – for many the first that they heard of their neighbours’ plans was when the planning notice came through their letter-box. Quite a few felt dissatisfied with the way that they were dealt by the Council, and some also reported unsatisfactory responses when they sought help from the Council for problems arising during the construction.

2.2. Although the survey was aimed at underground developments, most of what emerged probably applies equally to any major developments in residential areas, including the increasingly common total refurbishments involving the initial reduction of the building to a shell.

2.3. In terms of legislation, this is a complicated area, as achieving control over such development involves the planning regime; environmental health and noise legislation; building regulations; and the party wall regime, which is a private civil matter between the developer and the neighbours. There is an understandable tendency on the part of local authorities to leave as much as possible to be agreed between the neighbours themselves in party wall agreements. But from the neighbours’ point of view, it is usually more satisfactory for matters to be controlled by the public authority, as proceeding against a developer under the Party Wall Act is time-consuming and expensive.

2.4. We see all these regimes as having an essential role to play, and we believe that all of them need to be looked at to see if they can be used more effectively together to reduce the adverse impact of major residential developments. In some cases this may mean the local authority taking at least some responsibility for matters that it currently sees as for the PWA. Given the straitened times in which all public authorities are living, we have looked for solutions which do not involve, or involve only minimal, extra public expenditure. We think in particular that there could be an important role for voluntary guidance.

2.6. One issue that did not arise out of the survey was problems with flooding. However, the Association remains concerned that this is a serious potential risk that needs to be seriously addressed.

SECTION 3: NOISE AND VIBRATION

3.1 At least two-thirds of those respondents living in adjacent houses reported excessive noise and vibration. It seems that, however good the contractor, large-scale excavations under terraced houses almost inevitably cause a major nuisance for the immediate neighbours in terms of noise and vibration (those opposite were much less affected). But far too many respondents reported really intolerable situations, reflected in the following sample of extracts from the responses:

“Noise was truly excessive. Our whole house was vibrating all day. It almost drove me mad, as I work from home.”

“The noise was appalling. I could only work at night when they had gone. Kanga drills going all the time; cement saws going all the time. The most incredible noise you can imagine. I started to feel ill as a result of the construction din and my sleep was affected as I used to wake up [in] dread of the noise starting again for another day….I could not live through this ever again.”

“The builders have been great, but the noise has been extreme for the past six months, and as I work from home, the inconvenience has been dire.”

“Excessive noise. Unable to hear telephone or use it. The level of noise was unbelievable. The whole house shuddered.”

“There has been continuous noise and disruption from 8 am to to 5 or 6 pm sometimes….I have been trying to complete my M.Sc with great difficulty and had to leave my house on a regular basis to go to the Library or a friend’s place to study.”

“With digging, so far I have not been able to stay in my house during work due to noise and vibration.”

“Noise levels of drilling, digging (so deep), vibrations were deafening. In addition a giant concrete mixer was operating outside from 7.45 am to 6.30 pm, every day including Saturday mornings….I was very ill at the time of the building and couldn’t have moved, but it was very traumatic.”

“Excessive noise is an understatement.”

“Excessive noise, dust, vibration – we’re two years in and probably another 18 months to go. One of us runs a consulting business, another is an OAP who is at home all day. The contractors are friendly, but this work has ruined our home and our day-to-day lives here.”

“Excessive noise, dust, vibration in spades. Ten months of drilling etc, with noise measured at 120 decibels outside and 195 decibels inside the house. Another three months of similar noise while sewers were dug up. A compressor was outside the house continuously operating all day with no lunch break, 76 decibels measured inside the house, 96 outside. I have lost some hearing. My elderly mother suffered palpitations and I believe the works were largely responsible for her dying when she did.”

3.2. There were also several complaints about workmen playing radios. Although this cannot compare with the noise of construction, it seems to have particularly irritated a number of people to have even the quiet periods spoilt by loud music not necessarily to their taste.

Solutions: achieving a better balance between development and environmental considerations: amendments to planning rules.

3.3. Given the inevitability in so many cases of really horrific noise, vibration, etc, however good and considerate the contractors are and however zealous the Council in enforcing noise conditions, and given that people suffer very real effects, we are of the opinion that the time has come for a thorough rethink of the controls on the planning and execution of major works in residential areas.

3.4. The current situation means that it is extremely difficult to take any action against excessive noise from building works. At the time that the present environmental legislation was enacted, building works in residential areas tended to be fairly small-scale and rarely lasted more than a few months. Nor did they often involve heavy drilling. Now, with increasing wealth and the increase in land values, the situation has changed dramatically. It is becoming commonplace not only to undertake major developments under buildings, but also to undertake the sort of major refurbishment that involves removing and then rebuilding most of the inside of a building – a procedure that can also involve equally intolerable noise and dirt. Much noisier methods are used and eighteen months is standard for a major underground development or complete refurbishment. Indeed, our survey showed that many developments last up to three or four years.

3.5. All the indications were that the balance between the desirability of allowing these developments and the right to neighbours in residential areas to a peaceful family life and peaceful enjoyment of their property is now thoroughly skewed. We believe the time has come to look at a change in planning controls so as to allow Councils to refuse planning permission where approved noise standards during construction cannot be met. Although it is possible, after planning permission has been granted, to take action under environmental legislation, it is extremely cumbersome to use, and it would be simpler for all if this matter could be dealt with by planning conditions imposed at the outset.

3.6. We also see a case for directly balancing the nuisance to neighbours in residential areas against the desirability of developments. If a development is going to increase the housing stock, provide extra living accommodation or help e.g. the economy of the area, then allowing it may be considered appropriate even if major nuisance to neighbours is expected. But for less essential developments, a Council should be enabled to take the view that the nuisance will be too great.

3.7. One complaint is that too many of these developments take place in the same area, subjecting residents of that street to years of continuous noise. One planning lawyer suggests that the Council could take the position that, although one basement causes insufficient nuisance to be noticeable under the planning regime, a whole street of them could be considered noticeable, and therefore the Council could refuse permission on precedent grounds. The case law in support of the principle that planning permission may be refused because of the precedent effect is Poundstretcher v Secretary of State for the Environment [1988] 3 PLR 69. The Council may wish to test this out.

3.8. Even if successful, that would only deal with part of the problem. We see a case, therefore, for the planning rules to be amended to provide specifically for planning approval to be withheld where appropriate to ensure that there is a decent interval between noisy developments in the same street.

3.9. We propose to lobby for such changes and hope that the Council will do so too.

Solutions: a code of practice on minimising adverse impact.

3.10. Even though the present legislation is in our view inadequate, we believe that there are various steps that the Council could take within it to mitigate current problems. These include both operating the present controls in a more efficient way, including a more collaborative relationship between the planning and environmental health regimes; and exerting moral pressure through guidance, etc. We were particularly impressed with the “Code of Practice for Deconstruction and Construction Sites” issued by the Corporation of the City of London for work within their area, and some of the ideas below draw on that document. Although the City has a preponderance of very major developments, there seems no reason why most of the principles set out in that code should not be applied to major domestic developments in RBKC. The big estates, such as the Grosvenor Estate, also have their own guidelines and requirements that it would be well worth looking at.

3.11. We welcome the decision of the Council to consider attaching a condition to planning decisions (NEW5) requiring builders to be members of the Considerate Contractors Scheme and hope that this condition will become standard for all significant underground developments. The Considerate Constructors’ Scheme Code, however, is basically a set of principles and a list of items that builders need to think about and on which their performance is judged. It does not set out any specific standards. It also applies only to the constructor. We believe that there is a strong case for an additional guidance document from the Council which covers the whole of the development process, including what is expected of contractors on such matters as noise. The advantage of such a document is that it could exert moral pressure (which should not be under-estimated) and give the Council a better basis for taking action against noisy developers under legislation on environmental pollution.

3.12. The Council has a powerful tool under the Control of Pollution Act 1974, namely the power to serve a “Section 60” order imposing requirements on how the works are to be carried out. The Council rarely uses this power, partly we understand because of the difficulty of setting appropriate standards (as contractors can appeal against anything unreasonable). It also requires considerable work for the Environmental Health Directorate (as each order would have to be based on an assessment of the individual circumstances) for which it does not have adequate resources or expertise. But if an applicant has signed up to a code of practice, and then deviates from it, that would place the Council in a much better position for serving an order

3.13. So far as we are aware, nobody has ever tried to bring a case against noisy building works under the general law of nuisance or under the Environmental Pollution Act 1990. Given the success that has on occasion been achieved over cases involving for example church bells or cocks crowing, which most would feel are infinitely less problematic, it is far from obvious that such a case would fail, if sufficient evidence was brought forward of unreasonable disruption to neighbours’ lives (there would need to be noise measurements, diaries, witnesses etc).

3.14. This is something that a future sufferer may wish to consider. In any case, the possibility of such action (as well as the possibility of Section 60 action by the Council) is something that all constructors should bear in mind. The fact that following the code of practice from the council could serve as a defence should be a powerful incentive to good practice.

3.15. Annex A shows the sort of thing we have in mind. This is something that all (or a group of) London Councils might consider issuing on a joint basis.

3.16. We therefore urge the Council to back up the Considerate Constructors Scheme with its own more detailed and wider-ranging “Good Development Guide”, applying both to the owners of the houses being developed and the contractors. This could figure as an “informative” (i.e. a statement drawing attention to requirements that may apply, other than those covered by planning conditions) in the planning permission. This would be publicised both to the developers/contractors and to the neighbours so that everybody was clear about what the Council expected of them. See Annex B for what such a Guide might cover.

Solutions: using quieter equipment, material and methods: action at the planning stage.

3.17. The main noise probably comes from pile-driving; compressors; and drills used to break up concrete and other materials. Constructors are already supposed to use the quietest reasonable equipment and methods. But it is far from clear that this actually happens or that significant attention is paid to looking at using the least noisy method. There are for instance a number of types of piles and ways of ways of installing the necessary piles for basement development, some quieter or less vibrating than others (sheet piles, system zero piling, continuous flight auger, use of self-compacting concrete, conventional underpinning, etc). In many cases, certain methods will be impractical because of the nature of the site. But often there will be a choice, and quietness should be the main consideration. Similarly, equipment such as compressors are made to different standards, and it is important that the quietest available and suitable is chosen (there are standards for such equipment). The major noise caused by breaking up concrete can be at least partly avoided by inserting weak break-points into concrete when it is cast.

3.18. It is far from clear that at present enough attention is paid to ensuring that quiet methods, material and equipment are used. We welcome the Council’s decision to require a construction methods statement (CMS) for underground developments at the planning permission application stage, and we also welcome the fact that the Environmental Health directorate of the council (who are responsible for noise policy will be looking at these. But we note that the items for inclusion in the CMS listed in Chapter 6 of the recent Supplementary Planning Document (of May 2009) on subterranean development does not include a requirement to address how noise and vibration is to be minimised in terms of methods and equipment to be used; it refers only to a sequence of the works being adopted that mitigates the effect on neighbours.

3.19. Another problem with construction method statements at the planning application stage is that they are inevitably pretty general, and we recognise that, at that stage, it may not be possible for the developer to be very precise on methods and equipment.

3.20. A further problem is that building techniques and equipment for these complicated projects constitute a very specialist field that is evolving all the time. Inevitably, Councils themselves are unlikely to have the necessary expertise on their staff. The Council has decided no longer as a matter of routine to employ an independent structural engineers to check construction methods statements for basement developments, a decision which we can appreciate, not least because we understand that the independent engineers rarely, if ever, disagreed with the structural engineer employed by the applicant There could, however, be more of a case for appointing relevant experts to advise on this narrow and specialised area.

3.21. We accordingly urge that:

- The Council should require the construction methods statement at the application stage specifically to address – if only in outline – how noise and vibration (and dust) are to be minimised by use of appropriate materials, methods and equipment. This would force the applicant to consider this issue from the outset and demonstrate that the Council takes it seriously.

- Applicants should then be required (through a planning condition) to produce a fully detailed CMS before the works begin on the materials, methods and equipment to be used to minimise noise, vibration and dust. This should be signed off by an expert in the relevant techniques. This requirement should not be unduly onerous, as any well-run major project should involve a more detailed methods statement to be prepared before the work starts. (An alternative to this two stage arrangement could be a separate Environmental Management Plan, the solution adopted by the City of London; the Development Impact Plan required by the Grosvenor Estate could also provide a model.)

- The detailed CMS should inter alia state what maximum levels and types of noise are expected over what periods (see paragraphs 3.26-3.30 below) and should set out arrangements for monitoring noise and vibration levels (including appropriate measuring equipment).

- The Environmental Health Directorate should be fully involved, and should be prepared where appropriate to discuss more appropriate methods or equipment with the applicant. While the Council may not have the resources to check fully every detailed CMS statement, it should do so at any rate where there is deviation from the original statement, or where there are particular concerns; and if necessary seek appropriate advice from an independent expert on e.g. the methods and equipment proposed to be used.

3.22. If the Council uses independent experts, under the current regime it must pay them out of revenue from the tax-payer, because planning fees are fixed by the Government and cannot be increased to cover such extra expenditure. It seems to us entirely fair, however, that the applicant should pay for whatever independent expertise is needed to ensure sustainable development and the proper operation of the planning regime. We understand there is unimplemented legislation which would allow Councils to set their own planning fees, which could take account of such costs. We would urge that this is brought in as soon as possible.

Solutions: using quieter equipment, material and methods: action at the construction stage

3.23. Although a planning condition can be imposed requiring a CMS, there also needs to be an assurance that it will be followed. The Council takes the view that its powers under planning legislation are limited in this respect. But if an applicant has provided a CMS (or signed up to an Environmental Management Plan) with the standards that they propose to follow (e.g. as regards maximum levels of noise or the noise standard of the equipment used) and the noise levels expected, it should be easier to issue a Section 60 notice requiring these standards to be followed, as the CMS would be half-way to consent. In other words, some imaginative collaboration between the planning and environmental health parts of the council could achieve mutually desired ends.

3.24. There are problems over setting noise standards, as it is not just the intensity but also the duration and type of noise – continuous noise can be more upsetting than periodic short bursts of louder noise, and some relatively quiet noise may be more unpleasant than loud noise because it is at a particular frequency or is accompanied by strong vibration. Nevertheless, we believe that it would be worth the Council noise experts seeing if some rules of thumb on acceptable and unacceptable noise levels and types of equipment etc. could be developed as general policy guidelines, to indicate that if contractors keep within them, the council is unlikely to issue a Section 60 order or take other enforcement action. The developers would also need to put in place a permanent survey to measure the noise.

3.25. We would therefore urge the Council:

- To make the planning and environmental health regimes work together by using noise standards agreed by the developer in his CMS as the basis for enforcement action under S.60 of the Control of Pollution Act 1974;

- To develop some general guidance on acceptable noise standards for construction work, if necessary with the help of outside experts.

Solutions: keeping noise nuisance within certain hours

3.26. The Council helpfully adds to planning permissions an Informative drawing attention to the “standard” hours for building work, namely 8.00-18.30 Monday to Friday and 8.00-12.30 on Saturday. They would normally take enforcement action if it can be shown that contractors have caused a nuisance by working beyond those hours.

3.27. However, it is clear from the survey that some neighbours would prefer other arrangements, for instance a quiet period in the middle of the day. It may also be appropriate to limit particularly noisy work to specified hours, eg heavy drilling to mornings only – as when people know what to expect when, they are less likely to be upset and can take evasive action.

3.28. This is not an entirely easy area, as what one neighbour prefers may not suit another. There is also a trade-off between the daily hours worked and the total length of the problem. In many cases, it may be best for such specific arrangements to be left to the PWA. But we believe that this would be easier if the Council were prepared to make it a stated policy that, where there is agreement between the neighbours on what hours are preferred, and what is proposed is not unreasonable from the developer’s point of view, these should be the hours to be observed. Here again, in such circumstances, it might be open to the Council to make a “Section 60” order under the Control of Pollution Act 1974 to enforce the hours proposed.

3.29. This seems to be the approach adopted by the City of London, which expects developers to sign up to refraining from noisy work between 10.00-12.00 and 14.00-16.00, thus giving the

neighbours at least four hours of peace and quiet during the working day; if there are complaints, the Council holds out the possibility of a Section 60 notice imposing these hours. The City of London Code of Practice also bans work on party walls outside 09.00 and 17.00 when noise and/or vibration could be transmitted to neighbouring properties. This is presumably aimed chiefly at businesses, but in the case of underground development it may well be appropriate to agree some similar limits on hours of party wall work which meet the needs of residential properties.

3.30. We recommend that the Council encourage developers, through the proposed Good Development Code, either to meet any particular needs of neighbours or to allow for specified quiet periods during the standard working hours.

Solutions: compensation for nuisance

3.31. Even if the quietest methods and equipment are used, the noise can still be pretty intolerable. The tight control of hours of work can mitigate the situation for those working away from home during the day. But it is particularly serious for those who are at home during the day, for whatever reason – and they include many who work from home or are confined by age or illness to home during the day. Whereas the owner of the property being developed almost invariably moves out, the neighbours usually cannot do so and are left to suffer the full horror. Where a neighbour lets his or her house or wishes to sell it, he or she can incur a direct financial loss. One respondent to the survey who lets his house is having to lower the rent, for instance, and houses are difficult to sell when potentially damaging building works of long duration are taking place next door.

3.32. We believe, therefore, that there is a strong case for some financial compensation to be payable in such cases by the developer. Where appropriate – for instance where the occupants of neighbouring houses work from home or are vulnerable for some reason – the undertaker of the works should ideally be required to provide for them also to move elsewhere during the most noisy phases of the construction or to provide appropriate financial compensation in lieu (we have heard of one developer who is doing just this). And in other cases, the developer should be prepared to pay financial compensation for noise (perhaps based on days when it exceeds a certain decibel level).

3.33. There would need to be primary legislation to achieve this on a compulsory basis, and we will be pursuing this. In the meantime, however, there is nothing to stop the Council promoting such payments as a matter of good practice. If both parties were willing, appropriate provisions could be included in the Party Wall Agreement. The Council could draw up an indicative scale of payments, perhaps based on the number of days that noise exceeds a certain number of decibels. Not all undertakers would be prepared to do this. But with moral pressure from the Council, at least some might.

3.34. We therefore recommend that the Council should encourage, through the proposed Good Development Code, those undertaking extremely noisy works to include in the party wall award provision for monetary compensation (it could suggest a scale, taking into account that the courts have powers to impose fines of £5,000 on individuals and £20,000 on businesses if noise is not abated) for noise nuisance (perhaps based on the number of days the noise exceeds a certain number of decibels), and possibly in extreme cases the payment of rental for alternative accommodation.

SECTION 4: MINIMISING THE RISK OF STRUCTURAL DAMAGE

4.1. Little evidence emerged from the survey of major structural damage to neighbouring properties developing after completion of the works (although most developments had been completed fairly recently and several respondents were fearful about the future). But possibly as many as four of the properties covered by the survey appear to have suffered major damage during the works. We accept that this normally happens in only a tiny minority of cases. But it is worrying that there have been so many in such a small sample.

4.2. The Council should ask an independent chartered structural engineer to look at these few cases to see if any common factors emerge or lessons can be learnt. There would be a cost, but it would not be great and this seems a reasonable use of tax-payers’ money.

4.3. Unfortunately, minor damage (and sometimes not that minor) seemed to be more common than not. A large number of respondents reported cracking to their walls and other similar damage, including the need to rehang doors, often several times during the construction, as walls shifted. In some cases cracks continued to enlarge after completion of the works. Typical responses were:

“Cracks in several places in my 1st floor flat as our building is still moving. No action yet taken as cracks are still getting wider.”

“There are numerous cracks at the top of the house, all of which are recent. There is a massive crack in one garden wall.”

“Cracks in back of house. Damage to plants, garden wall and trees.”

“We have suffered extensive cracking and movement to both the interior and exterior of the house.”

“Main damage was to chimney flues through insertion of steels through party walls”.

“Extensive cracks to walls. Two windows now out of alignment.”

4.4. It may be impossible to avoid all minor cracking to party walls, as any excavation causes some movement, however carefully done, and even minor movement can cause quite alarming-looking cracks. These should be put right by the developer under the Party Wall agreement. But neighbours may have to live with the damage for many months or years, first because the cracks cannot be repaired until after the work is completed and secondly because there can be lengthy disputes over what is or is not the responsibility of the developer. Moreover, if the developer were to go bankrupt, the neighbour might have little recourse. One respondent, a barrister, insisted on a provision in his Party Wall agreement for a sum to be held by the Party Wall Surveyors to cover such an eventuality.

4.5. It should also be possible to reduce the probability of other than very minor cracking appearing. We note that the Grosvenor Estate requires developers to make an assessment of ground conditions, to include advice from a recognised geo-technical expert, with calculations to demonstrate that the effect on adjacent buildings would be no worse than the “very slight” category of the classification of visible damage to walls, with particular reference to the “Boscardin” table – i.e. effectively cracks that are easily treated during normal decoration (approx. 1 mm). This seems to us a desirable standard to aim for, even though it may require some over-engineering.

4.6. The Council should, through its Good Development Guide, suggest that the Party Wall Agreement should provide for an appropriate sum (perhaps £10,000) to be put in an account held by the Party Wall Surveyors to cover the cost of putting right any damage, so as to guard against the risk of developers defaulting. In addition, neighbours should be recommended to insist that they are a named party on the builders’ insurance policy, as this makes it easier to claim.

4.7. The Construction Methods Statement should include a calculation along the lines of that required by the Grosvenor Estate, namely to show that the effect of the excavation on adjacent buildings should be in the “very slight” category.

4.8. The Good Development Guide and/or the Party Wall Agreement should provide for the developer’s contractor to rehang doors and windows as soon as a problem arises.

4.9. The current legislation effectively gives developers a right to damage neighbouring properties so long as they put right the damage afterwards. This is tough on the neighbours who so often have to live with damage for many months before it is repaired. Again, therefore, this could be an area appropriate for some sort of monetary compensation.

SECTION 5: DIRT, DUST AND RUBBISH

5.1 These were also a major issue for many correspondents. There were complaints that neighbouring houses and gardens were left covered in dust with little attempt at regular cleaning; and that piles of rubbish were left for long periods, attracting vermin. There seems to be a particular problem with gardens rendered unusable for long periods by dust. In one case there was concern that the cutting of stone and MDF (medium density fibreboard which contains formaldehyde) on the premises could cause real harm to the respondent’s new-born baby. The following extracts from the responses give a flavour of the problem.

‘The mess is diabolical. Pavement is inadequately hosed down and despite repeated requests, our front steps are hosed only infrequently. My front hall is therefore filthy. There is scaffolding which hangs over the pavement and drips. During snow melt, it created a sheet of black ice outside. We carried out similar works 3 years ago and the mess was never as bad.”

“Continuous mess of mud, dirt, dust, rubble, rats and mice (from drilling).”

“Dust was a major problem… A serious fall of rubble down two chimneys had to be cleared, but only after I drew attention to this. My roof was left with two large bags of rubble and several slates broken by falling debris and bits of scaffolding. Again I was never alerted that this had happened. It was discovered by my roofer.”

“The dust was terrible. There was a lot of stuff dropped on our front path, including some sharp lumps of metal.”

“Dust, dirt, vermin and noise 6 days a week for more than one year…. A significant decline of quality of life for more than one year”.

“At one point a column of mud covered the front of the house to the third floor.”

“Demolition rubbish on road resulted in three ruined tyres during the course of the project.”

“The entire garden was blanketed by dust and it was impossible to maintain… The garden figures in the “Gardens on show in London” and has suffered severe set-back and will take a year to recover fully subject to no further disturbance. Three years’ income to charity has been lost.”

“Our garden was ruined by dust and debris. We had an infestation of rodents.”

“Our garden was covered in dust and many plants died. No permanent damage, but the garden was unusable for one year because of dirt and dust.”

5.2. At least some of these problems could be avoided by more careful workmen and working methods. There should be specific provisions in the proposed “Good Development Guide”, e.g. as regards frequency of cleaning; clearing rubbish to avoid vermin; cutting stone off-site etc.

5.3. There should also be compensation for loss of use of gardens, which often became quite unusable during the construction because of dust, obstructions etc. The PWA provides for replacing destroyed plants but not the loss of amenity. Some people do pay compensation through the Party Wall Agreement, and there seems no reason why this should not be general practice. Again, this could be encouraged through the proposed “Good Development Guide”.

6.1. This was another area of complaint. Respondents complained about lorries blocking the road and access to their property; skips being noisily removed early in the morning to avoid the congestion charge; and long suspensions of parking bays. One person, for instance, was unable to have access to the passage to their side door for several months, but was told they had no redress under the Party Wall agreement. Respondents were generally not impressed with the response when they approached the Council:

“Contact with environmental health and parking supervision. Often slow and ineffective response.”

“Very poor response from RBKC highways division. It took weeks to get them to visit, to a situation that they themselves acknowledge had serious health and safety risks. Only after this acknowledgement did we reach a reasonable agreement with the constructors to use small lorries and stop blocking all our access.”

“Approached Parking Dept [on illegal double parking]. Treated rudely and nothing done, so haven’t bothered again.”

6.2. The Council’s powers are limited. They require all applicants of major developments to prepare a Construction Traffic Management Plan, which is vetted and often changed at the Council’s request. This covers such things as access arrangements to the site; the routing of construction vehicles; estimates for the parking suspensions required; and details of any hoarding on the pavement or road. Constructors also need to obtain specific authorisation for any hoarding on the highway – which the council will normally give if it is the best way of avoiding dust, dirt and noise. They also need to seek specific parking suspensions, and the Council may refuse these if there is too little parking space nearby, eg because of other works. Finally, the Council say that if there is any dirt or debris on the road, they have specific powers to deal with this.

6.3. It seems from the survey, however, that the main, problem is probably caused by lorries not using the suspended parking bays, but double-parking or parking in entrances and blocking them. The Council says that this is almost impossible to enforce against, as when enforcement officials approach, the lorries just move off. However, there have been occasions (including one revealed in the survey) where, following a complaint, the Council has been able to negotiate better practices with the contractor.

6.4. Particularly in narrow streets, there may be a case for a more restrictive policy on skips. We note, for instance, that the Grosvenor Estate, in the case of developments in private mews on the estate, severely restricts the use of skips to the removal of soil excavated from the basement; other debris must be bagged and collected by one small lorry at a time.

6.5. While we accept that the Council’s powers are limited, we think that there may be a number of minor measures that the Council could take to improve matters:

- One problem seems to be the difficulty people have in finding the right person to deal with matters, or in ensuring that follow-up action is actually taken. There is a hotline already: “Streetline”. There needs to be greater clarity about who people should approach for what problem, and arrangements to track action arising from calls.

- When called upon to help, the Council should do what they can to negotiate acceptable solutions between the contractors and the neighbours, as contractors are more likely to listen to them.

- To encourage contractors to keep vehicle movements and skip removal within working hours, the Council should ask for the Construction Traffic Management Plan specifically to cover expected hours of vehicle movements; and it should also cover this issue in its “Good Development Guide”.

- In narrow streets, or where there are particular parking problems, the use of skips should be restricted and the normal procedure should be for waste to be bagged up and removed by lorry.

- To minimise the length of parking suspensions, they should not be granted for periods longer than one month, after which renewal should be sought; and contractors should pay more for renewals.

- The Construction Traffic Management Plans should be put on the RBKC website along with the planning documents, so that neighbours are able to see what they contain.

7.1. There was quite a strong feeling among respondents that the Council could do more to police works. Quite a few of those telephoning the Council were pleased with the response. But a significant number found it difficult to find the right person to deal with their problem, and it was not clear that people understood the boundaries between the responsibilities of the different Council services – planning, environmental health, building control etc. Several seem to have put up with unacceptable practices (e.g. working outside permitted hours) that the Council, if approached, could have dealt with. There were also complaints about letters misunderstood and telephone calls not answered.

“[We contacted the Council] several times. ‘This is a neighbour-to-neighbour matter’ was the mantra.”

“Two complaints to RBKC [about rubbish] but to little effect.”

“I pointed out to the Council that the planning restrictions were not being adhered to, but they couldn’t care less.”

“Owner and contractor decided to go another 15 metres down without planning permission. When I informed planning they ignored me and told me it was a party Wall matter. Building Control refused to come and said everything was under control. By the time they came the hole was well excavated and dangerous to my house.”

“I contacted the Council a couple of times when noise carried on into the evenings but didn’t get anywhere.”

“Contacted the Council and all the people they told us to contact. It seems no one is responsible for anything that comes up.”

“Very unsatisfactory response. Frequently told to leave number and call would be returned in a couple of days, even when the problem was urgent. When I finally got to talk to somebody, they often did not understand the problem.”

7.2. Ideally there should be more frequent inspections of works. But this would be costly in terms of resources. Under present legislation, the costs would have to come from the Council’s general revenue. Successive Governments have set their face against charging for enforcement inspections through fees, on the grounds that this could encourage excessive and wasteful enforcement which it would be unfair to put as a cost on the fee-payer. This is an understandable view, but we do wonder if at least some minimal enforcement costs could not be allowed for in the fees

7.3. What is more important, however, is that the Council should respond promptly and effectively to calls from neighbours about problems. We therefore urge the Council:

- to improve its system of hotlines, or at least publicise to neighbours of underground developments the numbers to call (or addresses to email) in the event of problems, indicating whom to call for each sort of problem.

- to arrange for all follow-up action from calls to the hotline to be tracked so as to ensure that appropriate action has been taken.

SECTION 8: STARTING OFF ON THE RIGHT FOOT

Prior consultation of neighbours

8.1. One worrying fact to emerge from the survey was that in over a third of relevant cases (and probably more) there had been little or no consultation of neighbours of adjoining properties by the applicant for planning permission before the application was put in. In most of these cases, the first that neighbours heard of the proposals was when the Council planning notice came through their letterbox. As one respondent put it, “the owner didn’t seem to think we existed”. There was also concern in one case that the neighbours had misrepresented what they were doing. This absence of consultation must risk setting the whole process of development off on the wrong foot.

8.2. We accept that there is no obligation on applicants to consult their neighbours, and no power by the Council to compel such consultation. We nevertheless feel that it is good practice for there to be consultation of residents of adjoining houses in respect of any major works. In at least some cases, such consultation could lead to modifications acceptable to the applicant while mitigating problems for neighbours. And we believe that, when there has been consultation, there is less likely to be friction over any problems that arise subsequently, in the long run saving everybody time and money.

8.3. We therefore recommend that the Council should positively encourage such consultation. In particular:

- The Council’s “Good Development Guide” should encourage applicants to consult their neighbours before putting in an application;

- In particularly difficult cases, the Planning Department could offer to chair a meeting between the two sides and their advisers;

- The Council should do more to insist that plans are clear and comprehensible to the layperson. The aim should be to make it possible for residents of the borough to understand planning documents without having to employ specialist advisers.

Taking account of objectors’ views

8.4. Quite a few respondents felt that, during the planning application process, nobody in the council had listened to their views and that they were banging their heads against a brick wall. We accept that, in many cases the council, even if it sympathises with an objector, is bound to give planning permission because it has no grounds not to do so. This is not always clear, however, to the objector, and maybe the Council could do more to explain the situation to objectors. There is a brief reference in the Planning Applications Charter

(www.rbkc.gov.uk/Planning/General/planning_application_charter.pdf) to the fact that the council cannot refuse an application just because lots of people object. But this does not spell out why the Council’s hands are tied. The recently-issued LDF on Subterranean Development gives a good round-up of many of the constraints on Councils, but is very detailed.

8.5. We therefore recommend that the council should do more to ensure that objectors understand both the system and the limitations on the Council’s freedom of action with respect to underground developments. In particular, at the planning Committee meeting (which is usually attended by any serious objectors), when a decision is made to grant planning permission, the Chairman should take particular care to explain clearly that, even if it had wanted to, the Council cannot usually refuse applications for underground developments, even in a conservation area, as Government inspectors have determined that developments out-of-sight cannot be deemed to affect the character of the area; and that the Planning Committee can also take no account of nuisance to neighbours from the construction, as this is deemed to be a matter for building control or other regimes.

SECTION 9: PARTY WALL AGREEMENTS

9.1. All owners of adjacent properties who responded to the survey had concluded a Party Wall Award agreement. However, in three cases the work started before the PWA was in place. Although the Act prescribes that there should be an agreement or award before the works begin, at present the only way that the neighbouring owner can enforce this is to go to the courts to get an injunction, which is likely to be costly.

9.2. To help encourage timely conclusion of a PWA, we recommend that the Council should make a new Informative that the work should not start before a Party Wall Agreement is in place, unless the neighbours have consented to the works. This should also be an item for the Good Development Guide.

9.3. Many respondents were unhappy with the way that the PWA had worked. It was not clear that everybody had managed to find a really effective surveyor, or had ensured that all the relevant elements were in the agreement. It is also important, for instance, for neighbours to appoint their own surveyor and not use the one chosen by the developer (the latter is what is suggested by one firm of surveyors currently leafleting RBKC residents living next to proposed developments). One of the respondents had achieved a clause in his PWA making him a party to the contractor’s insurance policy, enabling him to claim directly from the insurers if necessary. This is just the sort of thing for people to consider. Although various pieces of guidance have been issued by various bodies (including central government and the Council), these are mainly about the mechanics of PWAs and do not say much about what could be included in PWAs.

9.4. The Ladbroke Association (perhaps in conjunction with sister bodies), therefore proposes to issue a guidance note on what could usefully be included in a PWA to make it easier to protect neighbours’ rights in the case of underground developments. It would be helpful if the Council would give its blessing to this.

Relationship between PWA and Good Development Guide

9.5. As pointed out above, if matters are to be improved, all the various regimes need to complement each other and work together. We see the proposed Good Development Code and the PWA as complementary. The Good Development Code represents the Council putting its weight behind various measures that can be taken voluntarily by the developer to minimise problems for neighbours. Some of these are matters that can appropriately be contained in and enforced through the PWA. The proposed Ladbroke Association Guidance will suggest to people what they might try to include in their PWA; the Good Development Code should cover much of the same ground and will back this up by applying heavyweight moral pressure from elected representatives.

THE LADBROKE ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 260627

December 2009

ANNEX A: SUBTERRANEAN DEVELOPMENT QUESTIONNNAIRE (sent out in February 2009)

The Ladbroke Association, the conservation body for the Ladbroke area, has had a number of anecdotal reports of problems caused to neighbouring houses by the construction of new basements to accommodate swimming pools, gyms etc. The Association has urged the Council to take stricter action on such developments. One of the difficulties in persuading the Council to take appropriate action is that we have very little firm data on the problems caused. This questionnaire aims to collect such data and is being sent to houses in Kensington next to (or opposite) a building where such a development has recently taken place. We would be most grateful for your cooperation in completing it. There is also an electronic version of this form on our website www.ladbrokeassociation.org .

| Question | Answer (please continue answers on a separate piece of paper if necessary) |

1. Address of your property | |

| 2. Approximately how long did the work on the subterranean development take? Did it take longer than originally predicted, and if so, how much longer? | |

3. What involvement did you have in the run-up to the work? For instance, did your neighbours or their builders consult you in advance? Were you able influence the plans? Were you given adequate warning before the work began? Did you have a Party Wall Agreement with your neighbour, and if so did you make any claims under it? | |

4. During the construction, was any damage caused to your building or garden, eg cracks in the walls, flooding, damage to trees etc? If so, please could you describe the problem. | |

5. Was remedial action taken by your neighbour or their contractors to deal with the problem? Was any remedial action taken satisfactory? If not, why not? | |

6. Do you consider that you were exposed to excessive noise, dust, vibration, parking problems, difficulty with access to your property, mess left on it or other nuisance during the construction? If so, please describe the nuisance and the adverse effects that it had on you. Could your neighbours and their builders have avoided problems by being more cooperative? | |

7. Did you contact the Council about any of the problems during or after the construction work, and if so, whom did you approach? Did they respond satisfactorily? | |

8. Since the development was completed, have any new problems emerged which you think were caused by the work, e.g. fresh cracking in party walls; flooding or problems with rainwater run-off; trees dying? If so, please could you describe the problems and say how they have been dealt with. | |

9. Do you reckon that you were left out of pocket financially as a result of the development work? If so, by roughly how much and why? | |

10. Have you any suggestions as to how the construction of such developments could be improved in future to reduce the problems for neighbours? For instance better consultation at the beginning of the process; restricting noisy periods; hot-line for complaints? | |

| 11. Have you any other comments or suggestions as a result of your experience? | |

| 12. We would be grateful for your name and an email address or telephone number, if you are prepared to give them, so that we can follow up any questions that arise from your answers. We will not pass your name or contact details to anybody outside the Ladbroke Association. |

ANNEX B: GOOD DEVELOPMENT GUIDE FOR RESIDENTIAL AREAS

This is an indication of the sort of things that could be in a “Good Development Guide” issued by the Council. There might be advantage in all affected London Councils preparing a joint document.

- Before planning permission is sought for any major underground development or major refurbishment, neighbours should be consulted and consideration should be given to whether changes can be made to reduce or remove any concerns they may have.

- The plans submitted for planning approval should be clear enough for a lay person to understand without having to employ specialist advisers.

- A fully worked up construction methods statement should be completed and agreed with the Council; it should also be passed to the neighbours before work begins. It should include a statement on how the developer intends to minimise adverse effects on neighbours, and a calculation on how other than minimal cracks in party walls are to be avoided.

- The developer should allow sufficient time to negotiate a Party Wall Agreement and no work should be started before a Party Wall Agreement is in place.

- Where a major underground development is undertaken in an old terraced house, some damage to neighbouring houses (such as minor cracking) is often inevitable and there is a minor risk of more major damage. The cost of remedial action will be covered under the Party Wall Award. But that relies on those undertaking the development being solvent. In negotiation of the Party Wall Award, consideration should be given to putting a sum in escrow to cover the possible costs of remedial action.

- The developer should identify residential properties close to the site likely to be seriously affected by the works. These neighbours should be warned in advance that work is about to begin and of the duration and major stages, and they should subsequently be informed about any changes to the work plans. In particular, warning should be given of the start of any activity likely to cause major noise or vibration (as people are less likely to object if warned).

- The builders on site or the site manager should liaise with the neighbours and to do their best to deal with any problems that arise during the works.

- Contact details of site manager or other person with appropriate powers should be provided for the neighbours for use where problems cannot be sorted out with the builders on site. A telephone number could be displayed on a display board at the site.

- The contractor should keep a log-book of complaints made and what action was taken. The Council may inspect this log-book at any time.

- The contractor must provide Environmental Health with a current 24-hour call-out number for use in case of a complaint or emergency.

- Hours of work should take account of the needs of neighbours. Generally, unless otherwise agreed, noisy work should be restricted to defined hours, so as to leave quiet periods of at least four hours during the normal working day.

- Noise and vibration should be kept to a minimum. Where new technology has been developed to allow the work to be done more quietly, it should normally be used. [The City of London Code of Practice specifies certain methods, equipment and materials to minimise noise, such as using fully silenced modern piling rigs and ‘super silent’ generators.]

- Noise monitoring should be set in place (with a measure of ambient noise levels before construction begins to provide a baseline). Vibration monitoring should also be considered to reassure neighbours that no structural damage is being caused.

- Dusty work like stone-cutting should be done away from the premises, as should the cutting of all materials such as fibreboard that may contain formaldehyde or other noxious chemicals. If this is not possible, dust extraction or suppressant techniques should be used (sheeting, damping down etc).

- Rubbish should be cleared away daily to avoid vermin; and dust and dirt should similarly be cleaned away on a daily basis. Spoil should not be left long enough for vermin to settle, and waste foodstuffs (including empty food cartons and containers) should not be left lying about.

- Lorries and skips should normally be brought in and out only during permitted working hours. No vehicles should be left idling and excessive revving of engines should be avoided. No lorries should park at the site except in agreed areas.

- Radios and other sound systems should not be played by the workmen if neighbours object.

- Entrances, gateways, passages etc. should not be blocked.

- Scaffolding etc should be erected in a way that does not compromise the security of neighbouring properties. If burglar alarms on neighbouring properties are set off by vibration, the developer should pay any call-out or other associated expenses.

- The fact that planning permission has been granted does not in itself grant immunity from nuisance actions. Some works could be so noisy and cause so much vibration as to fall within the Environmental Protection Act. Life in neighbouring houses can become unbearable. Anybody wishing to sell their house is likely to find it impossible to do so. Where excessive noise and vibration cannot be avoided, therefore, agreed monetary compensation may be appropriate for the neighbours affected. [The Council could develop a scale of compensation payments that it considers appropriate.]

- Where neighbours in adjacent houses work from home during the day when noisy work is in progress, and hours of work cannot be adjusted to meet their concerns, the cost of renting an office elsewhere or an equivalent monetary sum should be paid. The same principle should apply in the case of vulnerable invalids who are housebound and who are likely to be seriously affected by noise and vibration.

- Where appropriate, neighbours should also be compensated for the loss of use of their garden because of dust etc, in addition to the replacement of damaged plants.

- Underground development can cause cracks in the walls of adjacent houses that cannot be repaired until the development is completed. This significantly affects the quality of life of the inhabitants of those houses for possibly a long period, and again it may be appropriate to pay a sum in compensation if neighbouring buildings suffer significant cracks.

ANNEX C: OBJECTIVES OF THE LADBROKE ASSOCIATION

The Ladbroke Association is the conservation society for the Ladbroke neighbourhood. It was founded in 1969, the same year as the designation of the Ladbroke Estate as a conservation area, and is registered as a charity. Its objectives are:

● to encourage high standards of architecture and town planning within the Ladbroke Estate area;

● to stimulate interest in and care for the beauty, history and character of the neighbourhood;

● to encourage the preservation, development and improvement of features of general public amenity or historic interest in the area.

Further information (and application forms for those wishing to join the Ladbroke Association) can be found on the Association’s website www.ladbrokeassociation.org. or www.ladbrokeassociation.info (old website).