Keeping the Ladbroke area special

Cinemas and theatres

Our area has been surprisingly well-supplied with theatres over the years. The first to open, in the 1860s, was the 20th Century Theatre in Westbourne Grove. There was then the Coronet on Notting Hill Gate (just outside the Ladbroke area) that opened in 1898 as a theatre seating over 1000 – although it survived as a theatre only for 18 years before being transformed into a cinema. It has now returned to its roots and is run as a thetre by the Print Room. The old Mercury Theatre in Ladbroke Road was the home of the Ballet Rambert and also put on plays.There were Theatre Clubs in the 1940s and 1950s in Chepstow Villas. And until it closed in 2022 the Gate Theatre was one of the best pub theatres in London. The area is also the home of the Electric Cinema in Portobello Road, one of the oldest working cinemas in the country.

Below are accounts of the history of the 20th Century, Gate and Mercury Theatres and of the Electric Cinema.

20th Century Theatre

Entrance to the 20th Century Theatre as it is today.

Origins of the building

Until the mid-1900s, the block of Westbourne Grove on which the theatre now stands was farmland, part of a large rural estate that had been purchased by the Ladbroke family (rich bankers) in the mid 18th century. In the 1840s, however, when property developers began eying the area as suitable for housing for the rapidly expanding population of London. After the death of James Weller Ladbroke in 1847, it was sold by his nephew to a speculator called Thomas Pocock. Pocock sold it on immediately to another speculator, the Rev. Brooke Edward Bridges (this was an era when property development was a popular activity for rich clergymen). Pocock continued to be involved, however, as an agent for Bridges and eventually bought back the site sometime between 1852 and 1855.

The row of houses at 283-303 Westbourne Grove was built in 1851 either by Pocock or under his supervision. It is not clear when the theatre building was erected. The Ordnance Survey map of 1863 shows the building, adjoining but not yet linked to any of the houses. There is some suggestion that it started life as a parish hall for St Peter’s Church in Kensington Park Road (which was built in 1855-7). But it may have been custom-built as a theatre sometime in the early 1860s for its first manager. In any event, it was definitely operating as a theatre or music hall before 1866. (There have been claims that the theatre dates from the 18th century and was one of five “patent” theatres licensed to perform dramatic works. But this must be a case of mistaken identity, perhaps with an earlier theatre of the same name. Apart from the absence of any building on the site in the 18th century, the legislation on patent theatres was repealed in 1843.)

The building adjoined the back of No. 291 Westbourne Road (or 21 Archer Street as it was then), which became the entrance to the theatre. It also adjoined the back of No. 113 Portobello Road, around the corner, and backed onto the then Stanley Gardens Mews (which has now been replaced by the car-park and garden behind the Notting Hill Brasserie and Waterford House). So the complex constituted a T-shaped building with entrances from Archer Street, Portobello Road and Stanley Gardens Mews. It included a theatre on the first floor of the main building (a rectangular chamber with the stage at one end and a gallery at the other); a large hall below; and a number of other rooms.

Pre-war map showing the T-shaped theatre with access from Westbourne Grove, Portobello Road and Stanley Gardens Mews.

1893 refurbishment

In 1893 the theatre was completely refurbished. On 30 December, the Kensington News gave a detailed description of the refurbished building:

The grand hall is upwards of 60ft long by nearly 30ft wide. It is lofty, well lighted, and ventilated. The decorations are very handsome, being beautifully relieved with blue and gold. The floor is superb for dancing, and the stage a most magnificent, being nearly 30ft square, fitted with foot-lights and batten lights, and every convenience. There is a fine stock of well-painted scenery, and one of the handsomest drop scenes ever painted on fireproof material. At the back of the stage are two large and well-lighted dressing-rooms for ladies. The gentlemen’s dressing-rooms are below the ladies, with every convenience and fire-proof throughout. The grand hall is capable of seating between 400 and 500 persons; the combined accommodation for dancing purposes affords room for between 40 and 50 sets. The foyer, or minor hall, has every accommodation, and is lofty, well-decorated, ventilated and lighted, being suitable for “at homes” and small gatherings etc. The ladies’ boudoir, or Masonic room, is very select and reserved, being well-lighted and fitted with every convenience. There is a draw curtain in the centre so that if only half the room is required the curtain can be drawn across and two separate rooms made. The supper room, or lower hall, is most elaborately fitted up, as well as being prettily decorated. It is very large and capable of seating close on 300 persons for supper. Well-lighted and ventilated, there is ample accommodation for large parties, with every convenience. The refreshment room adjoining the large hall, is luxuriously appointed and most commodious. All the gas lights are enclosed, and are on the “Fulton Light” principle. As a precaution against fire there are no less than nine exits, but little danger is to be apprehended from this source, as the hall has been made fire-proof throughout*, and all the requirements of the London County Council have been so liberally carried out that the Council have granted to Mr George a certificate expressing their entire satisfaction with the building. Should any of our readers contemplate giving a concert, entertainment, ball, dramatic performance, tableaux vivants, an “at home” or a wedding party &tc., &tc., we can confidently recommend them to hire the Victoria Hall, where they will find every convenience imaginable and receive the greatest courtesy from the proprietor and officials.

*According to one magazine article, it was the only theatre in Britain that was licensed for stage performances with the proviso that all the furnishings in it had to be made of wool as a fire precaution.

Victoria Hall and Bijou Theatre

The building was originally named the Victoria Hall, and when it opened it was under the management of John Robert Burgoyne. He seems to have been succeeded first by Samuel Thomas Wadham, whose name is on a playbill of 1871, and then by W. Trist Bailey, recorded as proprietor and manager on later playbills of the 1870s. In 1888 the manager was Peter Joseph George Howard. In 1893, Mr George was the manager, and in 1897 Ann Susanna George (perhaps his wife or widow) took over the management. The price of the seats in the 1860s ranged from 1s 3d for the cheapest seats, up to 3s for reserved seats in the stalls.

In 1866 the part used as a theatre was renamed the Bijou Theatre, making a virtue of its small size. It continued to be called the Bijou, or the Bijou at the Victoria Hall, until 1924.

In its early years the theatre was used by a variety of small companies, mostly putting on farces and other popular entertainment of the music hall type. There was almost always a group of musicians – those were the days when people expected music as well as acting. In 1866, for instance, a farce was put on by “members of the two universities of Oxford and Cambridge”, with an “amateur orchestra”. Often the plays were by amateur companies in aid of good causes – an example is the performance was given in 1874 in aid of the Building Fund of All Saints parochial schools.

THE PROGRAMME FOR 6 APRIL 1870 All that Glitters is not Gold Madison Morton’s popular Drama, with Henry Irving, Philip Day, Hudson Liston, Walter Joyce, H.R. Teesdale, A. Charles, J. Vincent, Kathleen Irwin, Marie Brewer and Fanny Garthwaite. Mr George Honeywill sing one of his celebrated “Buffo” songs The Spitalfields WeaverThomas Haynes Bayly’s Comic Drama, with Henry Irving, J. L. Toole, H. R. Teesdale, J. Vincent and Miss Mordant. Mr John Caulfield of the Gaiety Theatre will preside at the Grand Pianoforte. The entertainments will commence at eight o’clock. Reserved seats 3s; second seats 2s; third seats 2s. Carriages may be ordered at Eleven. |

There were also some more serious and interesting plays, some of which were reviewed in the national press. For instance, Oscar Wilde’s Salome, which had until then only been performed (in French) in Paris, had its first English performance at the Bijou in 1905 – although it was apparently a somewhat amateurish production and was panned by the critic Max Beerbohm.

The Century Theatre and the Lena Ashwell Players

The theatre must have run into problems in the early 20th century, as from about 1908 to 1918 it was used as a cinema. Children were admitted for a penny and were given a bag of sweets or an apple on their way out.

In the early 1920s there were again some theatrical performances. Then in 1924 it was acquired by Lena Ashwell, an enterprising actress who had organised entertainment for the British troops during the First World War – a sort of one-woman ENSA. From one “concert party” under the auspices of the YMCA at the beginning of the war, she built up a series of companies of some 600 players who gave performances to the troops in places as far away as Jerusalem, Malta and Egypt. After the War, partly in order to keep some of the players in work, she founded the “Once-a-Week Company” to provide good cheap theatre in the outer suburbs of London. They put on a new play each week, performing each night in a different venue – usually in fairly grotty surroundings, such as unelectrified school halls, or on boards shunted over a swimming pool. Seat prices ranged from 8d. to 2s.4d.

It has been suggested that Lena Ashwell made her first appearance as an amateur at the theatre, playing with Sir Herbert Tree in Young Mrs Winthrop by Bronson Howard. However, there seems to be no evidence for this in her autobiography, which suggests that her first part was as a maid in a play called The Pharisee by Malcolm Watson, at the Grand Theatre, Islington in 1891. She acquired the theatre in Archer Street when she was already well established to give her players a central London base. She renamed it the Century Theatre. The players themselves were also renamed the “Lena Ashwell Players” and divided into three companies, two going round the suburbs and one playing at the Century. Although some of the acting was understandably a little rough, the theatre quickly acquired a reputation for interesting performances. In 1925, for instance, a newspaper article urged its readers to visit the Century, pointing out pointed out how easy it was to take the tube to Notting Hill and then a 15A or 52 “and the conductor will put you out, politely of course, at the very door of the theatre”. Plays began at 8 p.m. and were extremely varied, with works from authors ranging from Shakespeare, Dostoievsky and Ibsen to Somerset Maugham and Noel Coward.

One 17-year-old novice actor who joined Lena Ashwell’s company in 1925 was Laurence Olivier. He had in fact already appeared there, according to his biographer Donald Spoto, in the previous year while still at the Central School of Speech and Drama, when a lecturer at the Central School put on two performances at the Century theatre, under the auspices of the Lyceum Club Stage Society. The play was a new one called Byron by historian Alice law, and Olivier played the very small role of a Byzantine officer.

In 1925, Miss Ashwell gave Olivier small parts in Julius Caesar (he played a conspirator, a tribune and a “friend to Brutus and Cassius”); and as Prospero’s usurping brother in The Tempest. But he lasted in the company for only a month, mainly because of the pranks he played, like tearing or pulling down the back-cloth to expose the bottoms of the actresses changing behind it. The last straw was when the underpants of one of the actors fell down beneath his toga and Olivier laughed so hysterically that he had to leave the stage. Miss Ashwell sacked him forthwith.

The cast list for Julius Caesar on 16 November 1925 Julius Caesar……………………………..……A. Corney Grain TriumvirsOctavius Caesar………………………….………….Alan Webb Marcus Antonius………………………………Godfrey Kenton SenatorsCicero…………………………….…………..Layton Horniman Publius………………………………………..David Donaldson Popilius Lena……………………………………Philip Brandon Conspirators against Julius CaesarMarcus Brutus……………………………………Harold Payton Cassius……………………………………………….Neil Curtis Casca………………………………………………Weston Fields Trebonius………………………………………Layton Horniman Ligarius……………………………………………..Alan Webb Decius Brutus…………………………………….Patrick Gover Metellus Cimber…………………………………Frank Randell Cinna…………………………………………Lawrence Olivier TribunesFlavius…………………………………………Lawrence Olivier Marullus…………………………………………Philip Brandon Artemidorus of Cnidos……………………………Ernest Meads Friends to Brutus and CassiusTitinias……………………………………………Patrick Gover Messala……………………………………… Lawrence Olivier SoldiersStrato…………………………………………….Philip Brandon Lucius…………………………………………….Joan Handfield Pindarus………………………………….…..Margaret Badcock Calpurnia………………………………………….Honor Bright Portia………………………………………………Esme Church |

Lena Ashwell’s work to provide theatre for the suburbs received recognition from various quarters. In 1925 the Lord Mayor of London paid an official visit to the Century Theatre, to see a performance of The Great Adventure. Also in the audience were all the Mayors, Mayoresses and Town Clerks of the boroughs in which her companies played. In 1927 the Duke and Duchess of York (the future King George VI and Queen Elizabeth) visited the theatre to see a performance of A Message from Mars by Richard Ganthony, “in recognition of Lena Ashwell’s great social and artistic work in last eight years in presenting to the people of Greater London the best dramatic performances at prices they can afford.”

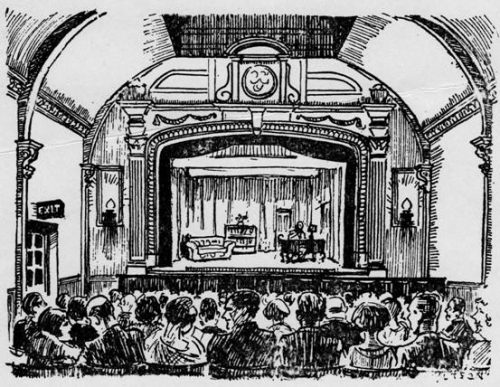

The Century Theatre in the early 1930s (courtesy of the lessees of the 20th century Theatre).

The 20th Century Theatre

The Lena Ashwell Players were disbanded in 1929 and there followed a period when the theatre was rented out chiefly for amateur dramatics. It was used by, among others, the dramatic societies of Harrods, D. H. Evans and the BBC. In 1936, the building was put on the market and in 1938 it was acquired by the Rudolph Steiner organisation, with Vera Compton-Burnett (a long-time adherent of Steiner’s Anthroposophical movement) as the manager and licensee. It was renamed the Twentieth Century Theatre and used for visiting lecturers and artists from Steiner’s headquarters in Switzerland and to popularise “Eurhythmy” or eurythmics – an expressive movement and music art invented by Steiner. The Steiner organisation continued, however, to make the theatre available for hire for theatrical purposes, with “due discrimination as to the class of entertainment”. A variety of small professional and amateur groups put on plays, both light and serious – the latter included in 1953 a production of Hyppolytus in Greek by Classical Society of King’s College London.

The Ballets Nègres, a mainly West African dance troupe, also put on several successful seasons there.

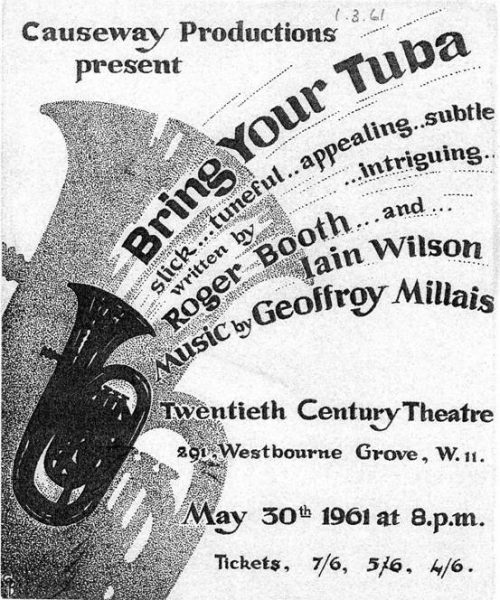

A 1961 playbill, for what was probably one of the last productions put on at the theatre (courtesy of the lessees of the 20th Century Theatre).

The Steiner organisation subsequently established permanent headquarters in Baker Street, and their departure brought to an end the building’s theatrical era. Running such a small theatre was a difficult economic proposition (in 1946, the reviewer Harold Hobson, described the theatre, “which is charmingly decorated in blue” as “about the size of the crush-hall at Drury Lane”). In 1963 theatre closed. The cherubs and proscenium were chipped away and the fittings were all stripped out, except in the entrance hall, which still gives a ghostly idea of the theatre’s former glory. The building was acquired by W. R. Jones, a Portobello Road antique dealer, and in 1972 it became a warehouse for antiques. The new owner did, however, save the building by persuading the authorities to give it a Grade II listing, as a rare survival of a rectangular hall-type theatre with a gallery along one end.

In 1999, the theatre was taken over by new lessees and entered a new incarnation as a venue for art and photography exhibitions, product and book launches, fashion shows and fairs, and also for private parties. Only the downstairs hall remains an antique warehouse. During the filming of the film Notting Hill with Julia Roberts and Hugh Grant, the theatre was used for rehearsals, and the roof garden shown in the film was constructed on the roof of the theatre.

Inside the theatre around 2000(courtesy of the lessees of the 20th Century Theatre).

Sadly, the lease of the theatre expired in 2016 and was not renewed and it is now closed. It has, however, recently been purchased by a musical foundation which is planning to open it as a chamber music concert venue.

Ladbroke Association 2009.

The Ladbroke Association has the copyright of this article. The material in it may be freely used provided that the Association is credited.

Sources:

Playbills and other papers in the Theatre Museum Archives

Papers held by the current lessee of the 20th Century Theatre

Survey of London, Volume XXXII: Northern Kensington (Greater London Council 1973)

Myself a Player, by Lena Ashwell, pub. Michael Joseph 1936

Laurence Olivier, a biography by Donald Spoto, pub. Harper Collins 1991

Census returns

Miscellaneous press articles

Mercury Theatre

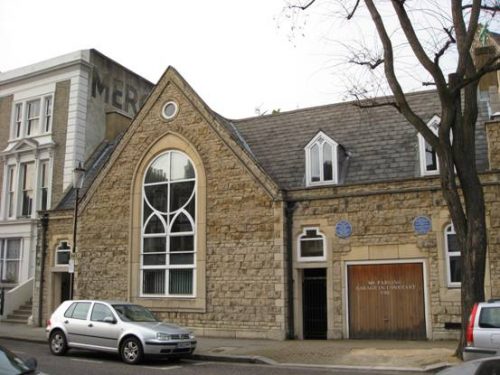

The Mercury today, with the Kensington Temple behind.

The Mercury Theatre was at 2a Ladbroke Road, next to the Kensington Temple. It is now a private house. The building, in what the Survey of London describes as a “free Gothic style”, was erected in 1851 by the Congregationalists of the adjoining Horbury Chapel (now the Kensington Temple), and began life as a school. The architect was John Tarring, who also designed the chapel. It was subsequently used as a church hall (“Horbury Hall”), and then briefly in the early 1920s the “Horbury Rooms” were occupied by the Kensington Local Pensions Committee. In the second half of the 1920s, the building was the studio of the Russian-Canadian sculptor Abrasha Lozoff (1887-1936), whose woodcarving Venus and Adonis, now in the Tate Collection, was almost certainly created there.

In 1927, Horbury Hall was purchased by Ashley Dukes, a successful West End playwright and theatrical impresario and the husband of Marie Rambert (later Dame Marie). The Russo-Polish ballerina had run a ballet school in Notting Hill Gate since 1919, and the hall was first used as studios for the school.

In 1930 Rambert founded the “Ballet Club” to give performances to the public, forming a dance troupe from her own pupils. It was the first classical ballet company in Britain and (as the Rambert Dance Company) is still going strong. The company first performed at the Lyric, Hammersmith, but in 1931 started putting on performances at Horbury Hall, which remained its home for the next 23 years. Ashley Dukes remodelled the building to meet the needs of both the Ballet Club and the ballet school. He put a partition through the middle of the old church hall, with the theatre on one side and a room for dance classes on the other. The steel beams that he inserted meant that the theatre was strongly enough constructed to qualify as an air raid shelter during the Second World War.

The first season opened on 16 February 1931. Contemporaneous press reports referred to the theatre as “small, but comfortable and attractive” and “a charming little band-box of a theatre”. It seated 150 people, including 15 standing at the back. The Ballet Club’s own literature described it as a private theatre, “equipped with a large stage and modern lighting. There is a spacious foyer for intercourse and refreshments”. Marie Rambert and Ashley Dukes tried to make a virtue of the theatre’s small size. The programme for the opening night stated the Club’s aims:

We are aware of the drawbacks of scene and perspective that accompany the presentation of Ballet in an intimate theatre. But we believe equally great advantages will be found in the enjoyment of dancing pure and simple.

For our part we mean this stage to serve the twin purposes of tradition and experiment. We shall preserve old ballets, the movement of which is now handed down from artist to artist by word of mouth alone; and we shall create new works that will bear transference to a larger scene as occasion offers….

A tradition of joky programmes was established. An early one told punters:

The exit doors are for emergency and lead you into Ladbroke Road double quick; we do not recommend them. It is more comfortable to go out the way you came in, especially as you can then visit OUR COFFEE STALL.

WE SHOULD HESITATE to recommend one of these establishments, especially in Kensington, where people go to bed much too early.

BUT WE MUST SAY A WORD for our own public stall, which not only supplies a remarkable cup of coffee (black if you prefer it or coloured with real milk), but also the following unusual delicacies:

Chipolatas or Midget Sausages as the larger stores prosaically call them, eaten impaled on orange sticks, and served both hot and cold.

Sardine sandwiches, buckling sandwiches, egg sandwiches and others too numerous to mention.

As there was no room for an orchestra, a pianist provided the music from a corner in front of the stage, sometimes accompanied by a harp, oboe or bassoon. People could dance on the stage following the performance. As today, there were parking problems. One programme in the 1930s apologizes “for the joint activities of the Metropolitan Water Board and the Borough Council which have momentarily made Ladbroke Road a devastated area. You will shortly be able to put your car outside as before”. In fact, the council seem soon afterwards to have insisted that patrons should park down the middle of Kensington Park Road. By 1938, Ashley Dukes had acquired numbers 1-7 Ladbroke Road opposite, together with the land behind (now Bulmer Mews) and patrons were instructed to park there. When war broke out the following year and an air raid shelter was erected in Bulmer Mews, patrons were directed to a garage opposite the end of Horbury Crescent.

Despite its modest premises and facilities, the Ballet Club attracted some major guest artists to supplement the Club’s own company. Alicia Markova, the star British ballerina of her age, gave her support and danced there regularly in the early days. The company also included the young dancer Frederick Ashton, subsequently Britain’s foremost choreographer. He choreographed one of the short pieces, “La Peri”, with which the first season opened (with Markova in the title role), and soon became the Ballet Club’s resident choreographer. Others who appeared there included Robert Helpmann (in 1934 and 1939) and Margot Fonteyn (in 1936).

The inside of the Mercury in the days of the Rambert Ballet (Courtesy of the Rambert Dance Company Archive).

At the beginning, only members and their guests could attend performances. The Ballet Club depended largely on subscriptions from its members (as well as subsidies from Ashley Dukes, who had made a lot of money from his West End successes). By the end of its first year, it had 1150 members, each paying a subscription of 12s.6d. Club status was a legal necessity both because until 1933 the theatre had no public performing licence, and to by-pass the restrictions in Britain on Sunday performances.

At first, the theatre had no name and was known simply as the Ballet Club. In 1933, Ashley Dukes, who was never afraid of experimentation, decided that it should become “The Nameless Theatre”. This name did not take off, however, and by the end of 1933 it was renamed the Mercury. Ashley Dukes wrote in the programme:

Mercury being the God of commerce, it is strange that so few play-houses are called after him. We have nothing against his mercenary attributes, but we prefer to think of his dexterity and charm, his musical inclination and his dalliance with the nymphs (whence Daphnis and Pan). Born in the morning he had invented the lyre before noon, and by nightfall had enticed a herd of fifty away from his duller brother, Apollo. May this be an omen of our own powers of lure, for we can find room for three times as many. All this knowing well that the god escorts men through adventures, and protects them in enterprises, and dances whispering prudent counsel in their ear.’ [From Marie Rambert, Quicksilver – an autobiography, by Marie Rambert (W & J Mackay, 1972)]

In 1936, Ashley Dukes bought the two houses next door to the theatre, numbers 2 and 4 Ladbroke Road. This enabled the facilities at the theatre to be considerably improved. A new entrance was created through No. 2 Ladbroke Road and proper bar facilities installed. The bar was decorated with an excellent collection of ballet and theatrical prints and drawings.

By 1934, the Ballet Club was giving two performances a week, and subsequently settled down to regular Sunday night performances. When the ballet was not performing, Ashley Dukes often put on plays and other entertainments. These included musical dramas by the “Intimate Opera” company, and also several seasons of “Plays by Poets”. Thelatter included the first London performance of Murder in the Cathedral by T.S. Eliot (in 1935 or 1936) and the premiere of The Ascent of F6 by W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood (in 1937). In 1939, the first English performance of Macchiavelli’s Mandragola was put on at the Mercury.

On the outbreak of war in September 1939, London theatres closed. But the Mercury quickly reopened (one of the first London theatres to do so) with a season of ballet in November 1939. The following year, however, the Ballet Cub merged with the Arts Theatre Club and moved to the Arts Theatre. Marie Rambert nevertheless remained very much a presence at the Mercury. Brigadier Stephen Gilbert, who lived in Ladbroke Road as a child at the beginning of the war, recalled how during the blitz she would ask the neighbours to shelter under the stage. “Apparently she found the bombing most inspiring and she would sweep baby me up into her arms and dance energetic fandangos.” [Stephen Gilbert, WW2People’s War. WW2 People’s War is an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC. The archive can be found at www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar]

Although the Ballet Club had moved out of the Mercury, Ashley Dukes continued to put on plays almost throughout the war, including more Plays by Poets. In 1943, for instance, the Evening Standard reported that, “if you travel to the terra incognita of Ladbroke-grove and locate the Mercury Theatre, you can now see a play by the Poet Laureate, John Masefield, The Tragedy of Nam”.

After the war, the Ballet Rambert (as it had become) had outgrown the Mercury and needed a larger stage. It became largely a touring company, making Sadlers Wells its London base and giving only occasional performances at the Mercury (it moved finally to its current headquarters in Chiswick in 1971).

In 1951, Marie Rambert’s daughter and son-in-law, Angela and David Ellis, set up a “Ballet Workshop” at the Mercury for new and experimental ballet productions. The Ballet Workshop continued until 1955 and Ashley Dukes also continued to put on short seasons of plays at the theatre until his death in 1959, although less and less frequently. Other companies also took the theatre for short periods. In 1974, for instance, the American-born producer Hal Rosenblatt took the theatre for a full season after having done occasional productions at the Mercury. And it was hired out for events whenever possible. In 1968, it was one of the locations for a Beatles photo-shoot by the veteran photographer Don McCullin. The Beatles had decided that they wanted some new “photographs with a difference” for the media and asked Paul MacCartney’s then girlfriend to choose five “random” locations in London, one of which was the Mercury. The Theatre also appeared in the film Red Shoes, where it was used to portray the venue at which the young ballerina played by Moira Shearer was discovered.

Most of the time, however, the ballet school was the main occupant of the Mercury. It catered both for serious ballet pupils and the many ballet-mad children of local families. Barres had been installed along the side walls of the auditorium and the seats were removed when there were no performances, leaving a fine space for ballet classes. There were also a number of other class-rooms behind the theatre and off the maze of corridors in the adjoining No. 2 Ladbroke Grove.

The Mercury before the rebuilding (courtesy of the current owner).

The inside of the theatre when it was being used for ballet classes (courtesy of the current owner).

Finally, in 1987, the Ballet Rambert decided to sell the theatre. There were no takers for it as a theatre, and it was reluctantly agreed that it could be converted into a private house. The building was by then in a bad state. It was purchased by a developer, who completely rebuilt the façade on Ladbroke Grove and transformed the entire building into an impressive and idiosyncratic dwelling.

The Mercury after the rebuilding. Note the old sign still on the side wall of No. 2 Ladbroke Road, where the entrance to the theatre used to be.

Ladbroke Association 2009.

Sources include:

Programmes and articles in the Theatre Museum Archives

Sixteen Years of the Ballet Rambert, by Lionel Bradley, pub. by Hinrichson Editions Ltd 1946

Rambert: A Celebration, compiled by Jane Pritchard, pub. by Rambert Dance Company 1996

This article is the copyright of the Ladbroke Association. It may be freely used so long as the Association is credited.

The Electric Cinema

Photo 2006

The article below on the history and architecture of the cinema appeared in the Summer 2001 edition of Ladbroke News.

Almost 90 years to the day after it first opened its doors, Notting Hill’s much-loved Edwardian auditorium, the Electric Cinema, now restored to its former glory, has once again welcomed cinema goers. Many locals, together with movie buffs and those who care about Britain’s cinematic and architectural heritage, will breathe a sigh of relief that the Electric, a fine example of an early cinema building, still exists. They should also be delighted with the refurbishment of its Edwardian decor and the entertainment facilities it now offers.

That the Electric did not meet its demise long ago, like so many of its contemporaries, is due to the determined refusal of successive RBK&C Planning Committees to grant change of use of the building, and to English Heritage’s campaign launched in late 1990 to save London’s best cinema buildings from demolition or inappropriate alteration. These policies, coupled with the vision and financial backing (nearly £6 million) of its new owner, Peter Simon, entrepreneur and founder of the Monsoon and Accessorize retail chains, have saved the Electric and seen it restored to a better condition than when it was built. So what has been achieved and why is it important?

For years the Electric has been beset by problems both structural and financial, as well as by lack of volition to maintain its original function. In the last three decades the survival of the Electric as a cinema has been frequently in jeopardy, although in 1972 it was granted a preservation order and it is now a Grade II* listed building.

The oldest purpose-built cinema in the country, the Electric was begun in 1910. [This claim is disputed by the Electric Cinema in Birmingham.] Built on the site of a timber and builder’s yard and incorporating bits of earlier buildings, it was powered by electricity, which had only just been installed in Portobello Road. It was designed by George Seymour Valentin, a young architect who worked in ‘Flicker Alley’ off Shaftesbury Avenue, then home to the developing British film industry. In those days cinemas were lighting up all over Britain in a wide variety of buildings. The more stringent safety standards in a new Cinematograph Act, which entailed the reconstruction of many early cinemas, meant the Electric’s own construction was rushed through. Its first film, Henry VIII, was screened on 23 February 1911. Despite the rush, the Electric set the standard in decor, facilities and safety provisions for other cinemas.

English Heritage has called the Electric ‘the quintessential and most ravishingly pretty cinema of its period’. The building sported various innovations. The front was faced in brick with trompe l’oeil designs in terracotta, though they proved too expensive to finish. A slate roof with roof-top dome, plus a stunning barrel-vaulted ceiling with ornate fire-proof plaster-work moulding, were supported by a cantilevered iron frame. Decorative friezes and painted ribbands surrounded the roof and wall panels, while instead of the normal proscenium arch, the screen had an unusual picture frame around it surmounted by a globe and golden arch. The safety and comfort of the audience were important too. The auditorium, which could house 600, included large, comfortable seats, fire escapes and a separate projection room (early nitrate stock film reels were highly inflammable). A wooden red and gold box office and beautiful mosaic floor that picked out the original name, The Electric Cinema Theatre, completed the front of house. The Electric soon attracted a wide audience.

Yet, the Electric’s design had inherent flaws. There was little space for foyer, box office, offices, storage and toilets. Opened 18 years before the introduction of ‘taIkies’ in 1929, the Electric had no facilities for sound, and was more suited to live performances: ‘a music hall with a screen’, commented one cinema specialist.

Even its financial probIems began early. In 1919 it was renamed The Imperial by Mr Harry Hyamson, the first of a number of proprietors to encounter cash flow problems in running it. But crucially it was Hyamson who wrote into the Electric’s lease that it must always be a cinema. This far-sighted act prevented its subsequent redevelopment.

The Electric/Imperial’s golden age was the 1930s and 1940s when it attracted weekly audiences of up to 4000. In 1938 a leading cinema architect, George Coles, was commissioned to design a new stream-lined frontage with a projecting ‘fin’ on the façade, The London County Council granted planning permission in May 1941 but the scheme never went ahead.

The Electric’s decline began in the 1950s when its owners were unable to maintain the building. By the 1960s it was a dilapidated example of an early purpose-built ‘flea pit’ known locally as the Bug Hole. The roof leaked, seats collapsed unpredictably, the plumbing and drainage were elderly and liable to flooding, heating was minimal, the carpets were filthy and the audience was aging, if loyal. But the atmosphere was relaxed and friendly.

In 1968 the Electric Cinema Club was formed with the aim of showing alternative films and of combating the cinema distributors’ imposition of bland box-office hits at the cinema chains they controlled. In December 1970 the Club took over the premises and gave the Electric a new lease of life as a leading ‘alternative’ London cinema. The building was decrepit, but the tradition, character and atmosphere were maintained. £50,000 was spent on seating, heating, sound and projection equipment, and roof repairs, and the preservation order was granted. But yet again financing major structural repairs proved a problem.

From 1911 to 1983 the EIectric had never closed for more than at few days, except between June and September 1945 following a fire in the projection room. But in 1983 closure seemed imminent. The staff formed a cooperative to bid for the building, but an offer from Mainline Pictures (owners of the Screen chain of cinemas), was accepted, and on 31 October 1983 the Electric closed for renovations. The interior was restored, and the original plasterwork was picked out. An Indian poster artist, Narinder Singh Plahay, was commissioned to recreate in paint Valentin’s original tile design. Plush seating, air conditioning and Dolby stereo sound were all installed. But no structural repairs were undertaken.

Re-named the Electric Screen, the cinema reopened on 8 March 1984 and concentrated on first-run single features. But these did not attract the audiences required. Mainline decided to sell: in April 1987 the building was bought amid rumours that it was to be turned into an antiques market. At the same time the Campaign to Save the Electric Cinema was born with the aim of persuading the new owners to sell so it could be reopened as a working cinema. A petition opposing change of use obtained 10,000 signatures, including those of Audrey Hepburn and Anthony Hopkins. Despite the lobbying, on 6 May 1987 the doors closed again. Empty and shuttered the Electric again faced an uncertain future.

A succession of other new owners proved unable to resurrect the Electric. In 1989 restaurateur Martin Davis acquired it, restored the interior with the advice of English Heritage, revised the film programme and introduced live music performances. But in 1992 the building passed into the hands of receivers. An Afro-Caribbean company ran it for a time, but went bankrupt. By the mid-1990s the Electric was on the point of collapse. Receivers held the freehold which was sold in September 1996 and again in April requirements thwarted applications for change of use. In the 1990s local residents got used to the dismal sight of the Electric hoarded-up, neglected and covered in fly posters. The local council, nevertheless, made one last effort to preserve it as a cinema. Good fortune had it that by early 2000 Peter Simon had bought both the building and the supermarket next door. His aim was to ‘reconnect’ the Electric: to switch on the power again by forming a multi-purpose cinema, art, entertainment and leisure venue.

English Heritage had just launched its initiative to save the country’s historic cinemas. Together with the Twentieth Century Society and the local authority, a quite spectacular and ambitious restoration and development plan for the two buildings was put forward, thrashed out and eventually approved, in a private, public and voluntary partnership. 1998, as RBK&C’s strict planningrequirements thwarted applications for change of use. In the 1990s local residents got used to the dismal sight of the Electric hoarded-up, neglected and covered in fly posters. The local council, nevertheless, made one last effort to preserve it as a cinema.

Good fortune had it that by early 2000 Peter Simon had bought both the building and the supermarket next door. His aim was to ‘reconnect’ the Electric: to switch on the power again by forming a multi-purpose cinema, art, entertainment and leisure venue. English Heritage had just launched its initiative to save the country’s historic cinemas. Together with the Twentieth Century Society and the local authority, a quite spectacular and ambitious restoration and development plan for the two buildings was put forward, thrashed out and eventually approved, in a private, public and voluntary partnership.

Architects Gebler Tooth, whose commissions have included the Travel Bookshop in Blenheim Crescent, were chosen for the project. GT have reinstated and refurbished the Electric as an historic cinema which fits modern-day requirements, while also modifying it for conferences and live performances. GT had to decide whether to reinstate original Edwardian features or make the cinema acceptable to the 21st century, given that both the building and the interior decoration were listed. Structural changes have included installing another level at the front of the building, putting timber decking on top of the original concrete floor and reinstating two original windows formerly covered by hanging light boxes.

Outside, Gebler Tooth have restored the terracotta, replaced the rendering and cleaned the brickwork. Internally they have restored the mouldings and the globe in the auditorium, and the mosaic floor with the Electric’s original name in the foyer and vestibule, which are largely unchanged from 1911. With assistance from the Cinema Theatre Association and RBK&C’s archives, the architects researched the cinema’s appearance 90 years ago. Hence the colour-scheme of ivory with white mouldings and gilding reflects the French-inspired tastes of Edwardian England. Phoenix-like the Electric has been reborn, architecturally and functionally, as a muIti-purpose venue with bar and restaurant. According to Sasha Gebler, it is a marriage of the historic and the modern ‘without compromise to either’. Although the Electric will continue to face competition from its local rivals, the Coronet (opened as a theatre in November 1898) and the Gate, a vital part of Notting Hill’s heritage has finally been saved for posterity. Thankfully, as actor Michael Palin comments, there are still ‘people good enough to help landmark buildings like this to survive.’

Jan Brownfoot ©2001

With thanks for information and assistance to:

RBK&C Local Studies Library – for

numerous articles RBK&C Planning Department

Peter Simon’s PR Department

Gebler Tooth Architects

A detailed history of the cinema can also be downloaded from its own website www.electriccinema.co.uk

This page was last updated 30.6.2023

The Gate Theatre

Until recently, there was a pub theatre, the Gate Theatre, in an upstairs room of the Prince Alfred Public house at 11 Pembridge Road (probably the Ladbroke area’s oldest pub – it opened a year or so after Queen Victoria married Prince Albert in 1840 and was no doubt named in his honour).

The Gate Theatre was founded by the theatre director Lou Stein in 1979 – he turned down an assistantship at the National Theatre to create an artistic hub for upcoming artists. It was opened on a shoe-string – Lou Stein put an advertisement in Time Out saying “newly formed Fringe Pub Theatre at Notting Hill requires experienced, people, lights, sounds, also actors, no money but the prospects are good” – and it was probably the most cramped of the London pub theatres with a tiny room; comfort was definitely not its middle name. However, it soon developed a reputation for putting on interesting new or lesser-known works. It won numerous awards and many now well-known actors appeared there at the beginning of their careers.

Sadly for the neighbourhood, it closed in 2022 and moved to Camden Town.

This page was last updated 30.6.2023