Keeping the Ladbroke area special

Street furniture

This page contains articles that have appeared in our newsletter, Ladbroke News, on street furniture – drinking fountains and troughs and coal-plates. We plan to add more articles.

Drinking fountains and cattle troughs

In 1854, the physician John Snow famously proved that cholera was waterborne when he removed the handle from an infected street pump in Soho, thus preventing its use and greatly reducing the incidence of cases. This inspired a philanthropic M.P. called Samuel Gurney to found a charity four years later called the Metropolitan Free Drinking Fountain Association to provide the poor of London with fresh, clean water. Most of the infected water came from the Thames, into which untreated sewage was regularly poured. One of the Association’s rules was “that no fountain be erected or promoted by the Association which shall not be so constructed as to ensure by filters, or other suitable means, the perfect purity and coldness of the water.”

It was the age of great private philanthropy. Philanthropists and people wishing to remember loved ones quickly contributed funds. By 1879 some 800 drinking fountains had been erected in London. The charity was also, after some initial doubts, supported by temperance organisations which disliked the fact that beer was more readily available than water and many were sited opposite pubs. The evangelical movement also liked to see them outside churches, as a demonstration that the churches had the interests of the poor at heart.

One of the fountains built in the Victorian era still survives in the Ladbroke area, on Ladbroke Grove, outside St John’s church. It is made of polished granite and was funded by a local doctor who lived at 40 Ladbroke Grove and is inscribed: ‘The gift of John Waggett M.D. 1882.’ It replaced one that had been installed in the railings of the church in 1877 at a cost of £50. There are others just outside our area, including one in the railings of Royal Crescent Gardens on Holland Park Avenue (installed expensively in 1875 at a cost of £180) and one on ‘Turquoise Island’ in Westbourne Grove (installed in 1900 by a lady called Mrs Kirby who also sponsored nine other drinking fountains in London).

It was not long before the Association began to concern itself with the welfare of animals as well as humans. It changed its name to the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association and, in conjunction with the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, began to build troughs for cattle and horses. Cattle were in those days still driven by road from the country outside London and from the main railway stations to Smithfield Market and the Metropolitan Cattle Market off Caledonian Road and badly needed to be watered on the way. Horses and horse-drawn conveyances were of course an essential mode of transport and until then had had to rely largely on troughs provided by public houses for their patrons (one was apparently inscribed ‘All that water their horses here must pay a penny or have some beer’). Soon hansom cab drivers carried a map of the free fountains, since described as ‘Victorian filling stations’. Some thousand troughs were installed and in 1885, it was estimated that 50,000 horses drank daily from the Association’s troughs. Dogs were also catered for and many fountains had bowls at pavement level for their canine patrons.

By the 1950s, the troughs were so little used that the Association (which still exists as the Drinking Fountain Association) tried to give them to anybody prepared to pay to carry them away. There were a lot of applications, but applicants were soon put off on discovering that the average granite trough weighed some four tonnes. Many disappeared, however, during the building boom of the 1960s and 1970s. Most remaining ones are now used for planting flowers and shrubs.

Only three cattle and horse troughs survive in the Borough: one in Cromwell Road outside the Victoria and Albert Museum; one in Warwick Road; and one outside Julie’s Bar at Clarendon Cross. The latter was originally erected in Fulham Road and it is not clear when or why it was moved to Clarendon Cross. It is inscribed, almost illegibly on its sides, with an appropriate verse from Proverbs: ‘A thank offering to the God of Mercies. A righteous man regardeth the life of his beasts.’

This article first appeared in the Winter 2012/13 edition of Ladbroke News.

Coalhole covers

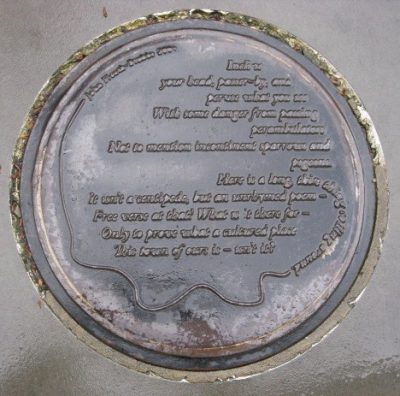

Residents of the area are probably aware of the local project supported by the Notting Hill Improvements Group and the Royal Literary Society that has resulted in seven new coalhole covers being installed around Notting Hill with specially commissioned texts from local writers (the person behind the project, the local artist, Maria Vlotides, has published a book about it called Pavement Poetry). Two of the covers are in the Ladbroke area and are illustrated here. There are others outside the Coronet and outside Daunts. Unfortunately the writing on these new covers is rather hard to read when one is actually walking over them.

There is also some interest in the old coalhole covers or “coal-plates” still to be found outside many houses in the area. In houses without deep front gardens, it was fairly standard practice for the coal-cellar to be built out under the pavement, and for the coal to be delivered straight into the cellar through the coalhole, so as to avoid coal-dust dirtying the house. Most coal-cellars were still in general use until the Clean Air Act of 1956, which banned the use of smoke-producing coal and speeded up the introduction of central heating.

The oldest coalhole cover is to be found in Norland Gardens and dates back to the 1820s. Most of those on the Ladbroke Estate date from the second half of the 19th century. The earlier ones had ventilation holes in them, as it was believed that damp coal gave off dangerous gases. But the holes let in the rain, making the coal even damper, and solid ones soon became the norm. There was a plethora of small ironworks dotted round London producing coal-plates, and each developed its own, often elegant, designs for its covers, as can be seen from the photographs below. All coal-plates were given raised patterns to stop passers-by slipping in wet weather. Many ironworks developed patent self-locking devices, with bolts that slid into place when the cover was replaced.

The main local ironworks was Jas Bartle and Co Western Ironworks in Lancaster Road, and many of their covers still survive. Retail ironmongers would order batches of coal-plates with their name on them for advertising purposes, and many covers have the name of R H & J Pearson and Sons in Notting Hill Gate, one of the largest wholesale and retail ironmongers in the area.

This article first appeared in the Winter 2012/13 edition of Ladbroke News.

Last updated 3.3.2014