Keeping the Ladbroke area special

History of the Ladbroke area

Until the 1820s, the 170-acre Ladbroke estate was farmland, with tenanted farms providing rental income for its owner. In 1819 it was inherited by James Weller Ladbroke, who began to develop it for housing, in response to growing demand from the rapidly increasing population of London.

Over the next 50-odd years, virtually the whole estate was built upon. Ladbroke had appointed a surveyor, Thomas Allason, to design a grand plan for the estate, with a north-south street (now Ladbroke Grove) bisecting the estate and a series of crescents and gardens on either side. With some alterations, this is the pattern that was followed.

The result was a series of streets with attractive stucco or half stucco houses, mainly in terraces but in some streets in the form of semi-detached villas; three large churches (one now demolished); carefully designed vistas and sixteen communal gardens, mainly accessible only to the residents of houses backing onto them. Although some buildings were destroyed during the Blitz, most of that 19th century development survives largely intact.

Timeline 1066-1841

The following are the dates of the main events before 1841 affecting what is now the Ladbroke conservation area.

1066: according to the Domesday Book, at the time of the Norman conquest the “Manor of Chenesitun” (Kensington) was held by Edwin, one of Edward the Confessor’s thanes. At that time it would have been mainly forest, part of the Forest of Middlesex.

1086: when the Domesday Book was compiled in 1086, the Saxon Edwin had been dispossessed by William the Conqueror and the manor had been granted to one of William’s Norman followers, Aubrey de Vere (or “Alberic de Ver” in the Latin of the Domesday Book). The de Vere family (who subsequently became Earls of Oxford) remained in possession of the Manor of Kensington for the next 500 years. Under the de Veres, the manor was divided into several different parts, one of which was the Manor of Notting Barns which included what is now the Ladbroke area.

1462: During the Wars of the Roses, John de Vere, 12th Earl of Oxford, and his son Aubrey were beheaded by order of Edward IV on account of their allegiance to the House of Lancaster. Their lands, including Notting Barns, were forfeit to the King. Notting Barns then seems to have passed to the King’s brother, subsequently Richard III.

1485: Henry VII, the first Tudor monarch, ascended to the throne. John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford, had taken his side at the battle of Bosworth Field, and was rewarded by the new king with the return of his lands, including Notting Barns.

1488: John de Vere needed to raise money on his estate and “the Manor of Notingbarons” passed into the hands of William, Marquis of Berkeley, Great Marshall of England. The Manor was then sold to the King’s mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby. The manor was valued at £10 per annum, and was described as “a messuage [dwelling], 400 acres of land fit for cultivation, 5 acres of meadow and 140 acres of wood in Kensington” (by this time the forest had been largely cleared and the manor was mainly farmland).

Lady Margaret conveyed the manor, along with other lands, to the Abbot, Prior and Convent of Westminster, with the specification that after her death the income from the lands should be spent on masses for her soul in Westminster Abbey and on the colleges and professorships that she had founded at Oxford and Cambridge.

1509: Lady Margaret Beaufort died. The Abbot of Westminster then leased the manor to a wealthy citizen of London, Alderman Robert Fenrother or Fenroper.

c.1518: Fenrother passed the lease of the manor to his eldest daughter, on her marriage to Henry White, gentleman. Land had probably been both added to and subtracted from the manor since 1488, as by now it was described as consisting of 20 acres of arable land, 140 acres of meadow, 200 acres of wood, 20 acres of moor and 20 acres of furze and heath. The Whites did not live on the Manor, but in neighbouring Westbourne. They died in the early 1530s and the lease of the manor was placed in trust for their children.

By 1540: Henry VIII had seized the lands of the Abbey of Westminster, including Notting Barns, but confirmed the land of Notting Barns to Robert White, the eldest son of Henry White.

1543: Henry VIII decided he wanted the “manor of Knotting Barns” and forced Robert White to exchange it for another manor in Southamptonshire. A deed dating from that year refers to “the Manor of Nuttingbarnes [the spelling continued to vary until the 18th century], with the appurtenances in the County of Middlesex and the farm of Nuttyngbarnes in the parish of Kensington”, so the manor at that time seems to have contained only one farm.

1549: Edward VI granted the Manor of Knotting Barns to Sir William Paulet, subsequently Lord High Treasurer and Marquis of Winchester.

1562: Sir William Paulet, being in debt to Queen Elizabeth, surrendered the Manor to the Queen.

1570: Queen Elizabeth I granted the manor to William Cecil, Lord Burleigh, her Secretary of State.

1599: Lord Burleigh having died in 1798, the manor was sold for £2,006 to Walter Cope, the builder of “Cope’s Castle” (Holland House).

1601: Walter Cope sold the manor of Notting Barns on to Sir Henry Anderson, Sheriff of London, for £3,400. It remained in the Anderson family until the death of Sir Richard Anderson, probably Sir Henry’s grandson, in 1765. The manorial system had more or less dissolved by then, however, and the ownership of the land that is now the Ladbroke estate may well have been sold off separately..

mid 1700s: Richard Ladbroke of Tadworth Court in Surrey, from a wealthy banking family, acquired the 170 acres of open country that is now the Ladbroke Estate. It was bounded on the south by what is now Holland Park Avenue; on the west by Portland Road and Pottery Lane; and on east by Portobello Road. It extended north almost as far as Lancaster Road. The land was open farmland at the time. We do not know from whom he purchased the land.

1773: Richard Ladbroke dies, bequeathing the land to his son, another Richard.

1793: Richard Ladbroke the son dies childless and bequeaths a life interest in the land to his mother and four sisters, with remainder to his nephews and then a remote cousin.

1819: The Ladbroke estate (still arable farmland) passes to Richard Ladbroke’s last surviving nephew, James Weller, who added Ladbroke to his name as required under Richard’s will as a condition of the inheritance.

1821: James Weller Ladbroke obtains an Act of Parliament allowing him to grant 99-year leases of the land (his uncle’s will had restricted him to 21-year leases), so as to allow him to begin building on the land. James Weller Ladbroke lived in Sussex, and left the active management of the development to the distinguished architect and surveyor, Thomas Allason.

1823: Thomas Allason draws up a plan for the development of the estate, with a broad straight road through the middle (now Ladbroke Grove); an east-west street called Weller Street (now Ladbroke Road); an enormous circus of some 560 yards in diameter just north of Weller Street (his plans for the circus were only partly realised); and a series of communal gardens or “paddocks”.

1823: James Weller Ladbroke signs what were probably the first two agreements to develop the land. The first is with Joshua Flesher Hanson, gentleman (the builder of Regency Square, Brighton) and covered the land between what are now Holland Park Avenue (then known as the Uxbridge Road) to the south; Ladbroke Terrace to the east; Ladbroke Grove to the west; and the southern part of Allason’s great circus to the north. The second agreement is with Ralph Adams of Gray’s Inn Road, brick- and tilemaker (who subsequently founded the pottery manufacture in the “Potteries”). This agreement covered the land between Ladbroke Road and Portland Road, except for a farm on the site of what is now the Mitre public house. Under the agreements, the developers had to build a certain number of houses and Ladbroke undertook to grant them 99-year leases of the houses when they were completed.

1824: Hanson arranges the erection of the houses at 8-22 (evens) Holland Park Avenue. He leased the remainder of his land to Robert Cantwell, an architect/surveyor/builder who later designed Royal Crescent. Cantwell was probably responsible for 2-6 and 24-28 (evens) Holland Park Avenue, built in the mid 1820s. At around the same time he built 1-4 Ladbroke Terrace (1-2 have since been demolished).

1825: year of national financial crisis which slows down the development.

1826-1831: Ralph Adams completes 14-32 (evens) Ladbroke Grove and 54-74 (evens) Holland Park Avenue (of which 62-66 have been rebuilt). He also completed most of the houses in Holland Park Avenue between Lansdowne Road and Portland Road that are now fronted by shops over their original front gardens.

1832: Ladbroke obtains another Act of Parliament to clarify obscurities in the badly drafted 1821 Act.

1833: John Drew of Pimlico, builder, completes 42-52 (evens) Holland Park Avenue, on the site of the farm; and 11-19 (odds) Ladbroke Grove.

1836: John Whyte takes a 21-year lease from Ladbroke of 140 acres of ground around the hill on which St John’s now stands, and lays out courses for steeplechasing and flat races (this race-course became known as the Hippodrome). See Hippodrome article below.

1837: first race meeting at the Hippodrome. But problems arise because the race-course is blocking a footpath between Kensington Village and Kensal Green.

1838: W.J. Drew, builder/architect, and William Liddard, gentleman, both of Notting Hill, complete 12-13 Ladbroke Terrace.

1839: Hippodrome race-course is altered to avoid the footpath. New opening meeting in May 1839, but the course is difficult because of the heavy clay and the Hippodrome runs into further problems.

Late 1830s: Cantwell completes 14-32 (evens) Ladbroke Grove.

1841: Hippodrome race-course closes.

1847: James Weller Ladbroke dies.

The remainder of the chronology is in preparation.

The Ladbroke family: from riches to poverty in one generation

This is an article that first appeared in the Summer 1997 edition of our newsletter Ladbroke News.

The modern thoroughfare of Notting Hill Gate and Holland Park Avenue follows the line of what was originally an ancient Roman road, leading from London to Uxbridge and the west country. Over the centuries a small settlement arose at the junction of the road with a narrow, twisting lane (now Kensington Church Street), leading south to another small village surrounding the church of St Mary Abbotts.

At the northern end of the lane, there was virtually nothing other than extensive gravel pits, the small hamlet of Notting Hill and a dusty farm track leading north to Porto Bello Farm; the surrounding fields and meadows remaining remote and inaccessible, well into the nineteenth century.

It is not known exactly when the Ladbroke family – wealthy bankers of Lombard Street in the City – first acquired their land in Notting Hill. However, by the time of Richard Ladbroke’s death in 1793, he owned estates in Middlesex, Surrey and Essex, as well as three separate parcels of land on the north of the Uxbridge Road. The largest of these amounted to 170 acres, roughly corresponding to the present Ladbroke Conservation area, bounded on the west by Portland Road and Pottery Lane, on the east by Portobello Road, with the northern boundary running along the present-day Lancaster Road.

Advised by his lawyers, however, James had always retained the freehold of his estate, so that, in the event of a builder or developer becoming bankrupt, the land would always revert back to him as ground landlord.

Richard Ladbroke’s fortune was eventually inherited in 1819 by his nephew, James, the surviving son of Richard Ladbroke’s sister, Mary who had married the Reverend Weller. Fulfilling the provisions of his uncle’s will, James Weller assumed the surname of Ladbroke and settled down on his uncle’s estate, at Tadworth in Surrey.

During his twenty-eight-year ownership of the Notting Hill estate, James Ladbroke appears to have lived the quiet life of a country gentleman; enjoying the income from his ground rents, and leaving the family lawyers to deal with the day-to-day business of running his estates. There is no evidence that he ever lived in Kensington, or was personally involved with the family banking business, which was taken over by Messrs Glyn & Co, in 1842.

No doubt encouraged by the building boom of the early 1820s, James Ladbroke’s solicitors – acting in conjunction with a distinguished architect, Thomas Allason – obtained a private Act of Parliament to develop the Ladbroke Estate. Despite their plans being affected by the financial crash of 1825, by the time of James’ death in 1847, leases had been granted to various builders and speculators, and what had originally been meadows and pasture-land, was fast disappearing beneath a sea of urban development.

Advised by his lawyers, however, James had always retained the freehold of his estate, so that, in the event of a builder or developer becoming bankrupt, the land would always revert back to him as ground landlord.

All that was to change with James’ death, when his estate was inherited by a distant cousin, Felix Ladbroke of Headley, Surrey, who had clearly made his plans well in advance of receiving his inheritance. Within two weeks of James’ death, he had transferred the administration of the estate to his own solicitors; sold the freehold of ten houses on the south side of Ladbroke Square, and also disposed of twenty-nine acres of land.

That was just the beginning of what was to be the complete break-up of the estate. There are very few records available about Felix Ladbroke. From the way he proceeded to handle his affairs, however, it would seem that he was not an astute businessman. By the time of his death, twenty years later, he had disposed of all his land in Notting Hill as well as his house in Surrey, and was living in ‘reduced circumstances’ near Victoria Station.

Unfortunately, the tantalising question as to exactly what Felix Ladbroke did with the funds raised by the sale of his large inheritance, remains unanswered. Whether it was lost through dubious City investments, or merely squandered on fast women and slow horses, the fact remains that he was, a relatively poor man when he died; the two small legacies mentioned in his will not being paid until after his wife’s death.

Mary-Jo Wormell

1997

The Hippodrome race course

This article is aken from the Kensington and Chelsea Public Libraries Occasional Notes no 2, January 1969, by Brian Curie, then the Local History Librarian. These notes were compiled from contemporary news-cuttings, prints and plans together with the following accounts, all of which may be seen in the Kensington Local History Collection at the Central Library, Hornton Street, W8.

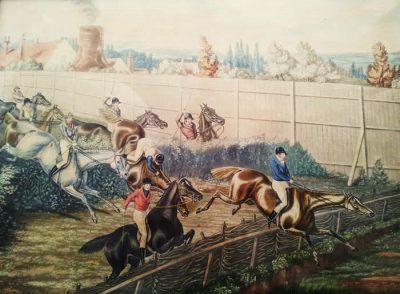

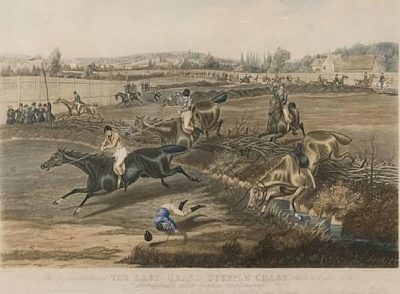

A race at the Notting Hill Hippodrome, by Henry Thomas Alken (the kiln of the Potteries is in the background).

The year of Queen Victoria’s accession, 1837, saw the inauguration of a new venture in West London – an attempt to establish a race-course which would rival Epsom and Ascot in its attractions. The prospectus, issued in 1836, stated that ‘an extensive range of land, in a secluded situation, has been taken and thrown into one great Park, and is being fenced in all round by a strong, close, high paling. This Park affords the facilities of a STEEPLE-CHASE COURSE, intersected by banks and every description of fence; and also of a RACE-COURSE distinct from the Steeple-Chase Course; and each Course is capable of being suited to a Four Mile Race for Horses of the first class.’

The founder of this enterprise was a Mr John Whyte of Brace Cottage, Notting Hill, who had leased about 200 acres of ground from Mr James Weller Ladbroke, the ground landlord. The course as originally laid out was bounded approximately by Portobello Road, Elgin Crescent, Clarendon Road and the south side of Ladbroke Square. The main entrance was through an arch at the junction of Kensington Park Road with Pembridge Road. It was also intended to provide facilities for all forms of equestrian exercise and for other out-door sports on non-racing days.

The first meeting was held on 3rd June, 1837, with three races for a total prize list of £250 and was followed by a second meeting on the 19th. Although it was agreed that the company was brilliant and that many ‘splendid equipages’ were present, the quality of the racing met with a mixed reception, one writer calling the horses entered ‘animated dogs’ meat’. Furthermore, Mr Whyte, in his enthusiasm to enclose the course, had blocked up a right-of-way that crossed its centre and which enabled local residents to avoid the Potteries, a notorious slum. Some local inhabitants took the law into their own hands and cut the paling down at the point where the footpath entered the grounds of the race-course. As a result, the crowds on the first and subsequent days’ racing were increased by the presence of unruly persons who, taking advantage of the footpath dispute, entered without paying for admission.

The next two years saw all attempts by Mr Whyte to close the footpath frustrated. There were summonses, counter summons, assaults, petitions to Parliament by the local inhabitants and the parochial authorities together with a wordy and scurrilous warfare in the columns of the press. There was even a plan at one time to make a subway under the race-course, but in 1839 Mr Whyte abandoned the unequal struggle and relinquished the eastern half of the ground.

The new course, renamed Victoria Park in honour of the young Queen, was extended northward to the vicinity of the present St Helen’s Church, St Quintin’s Avenue, and, as the prospectus pointed out, ‘the race-course [was] lengthened, and much improved; and without interfering with the rights of the public, the footpath, which intersected the old ground, will now run at the outside of the Park…’ A management committee composed of noblemen and gentlemen was formed and £50,000 capital was raised by the sale of £10 shares, the holder of two shares being entitled to a transferable ticket of admission.

Although the footpath question had been resolved, a more serious obstacle to the success of the venture soon became apparent. The soil was clay which made for heavy going and required extensive drainage. The nature of the ground made the course unusable at certain times of the year and this fault proved impossible to overcome. At the meeting held on June 2nd and 4th, 1841, the last race, a steeple-chase, was run. A set of four coloured lithographs, from paintings by Henry Aiken Junior, commemorate this event. In all, thirteen meetings had been held during the four years of the course’s history.

In 1840 a Mr Jacob Connop had been granted building leases for the eastern part of the race- course relinquished by Whyte and by March 1841 he seems to have become the proprietor of the race-course as well. By the following year Connop, in conjunction with another builder, John Duncan, was developing the estate for the ground landlord, James Ladbroke. Houses were built in what is now Kensington Park Road and Ladbroke Square but in 1845 Connop was declared bankrupt and the work had to be taken over by others. Thus it would seem that no one closely involved in the Hippodrome venture gained much from it and today the names Hippodrome Mews and Hippodrome Place remain to remind people that Notting Hill might under other circumstances have become another Epsom or Ascot.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea.

For further reading:

CATO, T Butler: `The Hippodrome, Notting Hill: a forgotten London race-course’ in Home Counties Magazine (14) 1912, pages 12-17 illus, plan.

CLIFFORD, Philip: ‘The Hippodrome at Notting Hill’ in The British Racehorse. December 1966, pages 562-565 illus, plan.

GLADSTONE, F M: Notting Hill in Bygone Days’. 1924, pages 81-89 illus. plans.

A speculating clergyman on the Ladbroke estate

These passages come from an article by the architectural historian Mark Girouard that first appeared in Country Life on 2 October 1975 under the Title “A speculating clergyman: Dr Walker in Cornwall and London”.

An intimate connection between a Victorian vicarage in Cornwall and rows of stucco houses in North Kensington seems, on the face of it, unlikely. One does not expect country clergymen to go in for property development on a huge scale, still less to go bankrupt (or all but bankrupt) owing £90,000, and have to leave the country. Such, however, was the curious story of Dr Samuel Edmund Walker (1810-69), London property speculator and Rector of St Columb Major, Cornwall.

The story came about because he had a rich father. Edmund Walker, senior, was a successful solicitor who indulged in a little speculation as a sideline. From 1809 until his death in 1851 he also worked in the Exchequer Office of Pleas, of which he became Master in 1832. The organisation of the London legal world in the early 19th century seems, nowadays, to be wrapped in Dickensian fog; but whatever it involved, Mastership of the Exchequer Office clearly brought in plenty of money, for Edmund Walker died worth about £250,000.

From this prosperous background Samuel Walker graduated at Trinity College, Cambridge, took orders, served briefly as a curate, and was then fitted out by his father with a prosperous living. As early as 1826 Edmund Walker had purchased the advowson of St Columb Major, Cornwall, for £12,000. It was a moderate sum for a valuable benefice, but the price must have been conditioned by the existence of a live rector, who had security of tenure until his death. This took place in 1841, upon which Edmund Walker presented the living to his son.

[Samuel Walker’s] father … died in 1851, leaving him, it was said, a fortune of a quarter of a million pounds. The innocent and hopeful son appears to have thought that by speculating in buildings he could increase their legacy to provide a really handsome endowment for [a proposed Cornish bishopric to be based at St Columb]. The full story has been worked out by the Survey of London in their invaluable Northern Kensington volume. As the Survey puts it (quoting from a contemporary obituary): “being ‘of a most amicable disposition, regardless of all selfish interests, sincere in the views he took, and truly religious in heart and life’ he proved ill-equipped for the hurly-burly of suburban speculations”.

After a preliminary, and unidentifiable, flutter in Gravesend Dr Walker turned his attentions to the Ladbroke estate in North Kensington, where the former Hippodrome racecourse was being sold off by the Ladbroke family for building. His father had had an interest in this in the early 1840s, but had sold out; it was probably this connection which drew his son’s attention to the area, with disastrous results. Between 1852 and 1855 he bought wildly, at top prices, and in the wrong places. In all he acquired 56 acres of freehold land in North Kensington, and contracted to buy another 34 acres. He expended, or made himself liable for, about £90,000. About half of this land was bought from the Ladbroke estate; and, in addition, to the east of this he bought, or contracted to buy, the southern 51½ acres of the Portobello farm. Portobello Farm belonged to two heiress sisters, the Misses Talbot, who on the strength of this and future sales retired to Bournemouth and devoted themselves to philanthropy and the building of a model village. In 1852 they had put the whole of the farm, amounting to 166 acres, up for sale, but the gullible Dr Walker was the only buyer; other developers considered, rightly enough, that the area was not yet ripe for development. Dr Walker was associated in his purchases with two old hands in the Kensington estate market, Richard Roy and Charles Henry Blake. Somehow, when the buying was over, Blake and Roy ended up with compact and desirable properties on the crest of the hill where Ladbroke Grove now runs, while Dr Walker was landed with a sprawling and much more dubious property down the hill to the north and north east.

Building began straight away. On the Walker land it fell into two groups. On what was to become Elgin Crescent, Lansdowne Road and the northern end of Clarendon Road, rows of stucco terraces began to go up. They were erected on building leases by builders whom Walker obligingly lent all the money they needed. He lent out some £60,000 in this way at no security except that of the houses they were building. The main borrower was a builder called David Allan Ramsay, but a number of others were also involved. The results were typical of speculative building at the time, and though agreeable were not especially distinctive; the houses had none of the amazing bravura of those designed by Thomas Allom for C. H. Blake in and around Kensington Park Gardens. Walker’s houses must either have been designed by the builders themselves or by minor architect-surveyors. The most entertaining are a row in Lansdowne Road, where the customary parapets are intersected by shaped Flemish gables, with agreeably eccentric results.

It seems unlikely that Dr Walker had much interest in these houses, except as a future source of income. His particular concern was on the Portobello end of his estate. Here in 1852, he started to build a church. This project was, as his projects tended to be, a grandiloquent one. The church was unusually large, its steeple was intended to be unusually high, and it was all faced with the best Bath stone. Moreover, next to the church he planned to build a rectory and a group of collegial buildings, connected with the church by a cloister. In the early 1850s these remained in the future; the surrounding houses, which were to provide the congregation, had scarcely gone beyond the sewers; but the church itself was rapidly approached completion.

It was dedicated to All Saints and the road on which it stood (now Talbot Road) was named St Columb’s Road. The architect, once again, was William White. He designed a church which, had it been completed, would have been one of the most memorable Victorian churches in London; and which still, without its spire and with an incomplete and largely redecorated interior, is a remarkably handsome building. The tower is extraordinarily elegant; the slim buttresses soar up for five stages with only the slightest of set backs and then become free standing, linked at the top by arches to an octagonal lantern surrounded by an arcade of marble columns. Above this is the truncated base of the spire, like the platform for a rocket which has taken off into space.

But before work on the spire could be started Dr Walker had sunk beneath “the floods of financial disaster. His speculations had got under way at the wrong end of a building boom. Supply far outran demand, and in 1854 there was a slump. The new houses found no buyers; Dr Walker, on the wrong side of the hill, was in the worst position of all. In February 1854 his main creditor and the main builder on his estate, D. A. Ramsay, went bankrupt. Dr Walker struggled on for a year; m February 1855 he was still hopefully buying and, but was quite unable to pay for it. In March he handed over the management of his estate to three trustees and retired to the Continent.

He left behind him a scene of chaos and desolation. His estate was covered with rows of empty or half-finished houses, or acres of mud interspersed by the beginnings of drains and roads. Out of the desert rose the unfinished hulk of All Saints, soon to be known locally as All Sinners-in-the-mud. Six years later the Building News described “the naked carcases, crumbling decorations, fractured walls and slimy cement-work, upon which the summer’s heat and winter’s rain have left their damaging mark . . . the whole estate was as a graveyard of buried hopes”. On Ladbroke Grove, a solitary pub, the Elgin Arms, stood alone “in a dreary waste of mud and stunted trees . . . with the wind howling and vagrants prowling in the speculative warnings around them”.

By then, however, the area was beginning to recover, as London inexorably expanded. All Saints, after five years of standing abandoned, was finished off in 1861, on the cheap and by a different architect. The unfinished houses were gradually completed, the derelict spaces filled with new building. Dr Walker managed to sell off what property he had preserved, and recovered sufficient credit to allow him to return and live in England.

He died in Hampstead in 1869 and did not live to see the final founding of a Cornish bishopric, based, however, on Truro rather than St Columb.

Reproduced by kind permission of Mark Girouard and Country Life.

The coming of electric light to the Ladbroke area

Sir William Crookes’ house at 7 Kensington Park Gardens (on the right). © Thomas Erskine 2006

This article was first published in the Winter 2013-14 issue of our newsletter, Ladbroke News.

Light bulbs as we know them were invented in the 1870s and in the early 1880selectric lighting began to be installed in houses instead of gas. To begin with, it was not very popular, as it was more expensive than gas and harsher on the complexion (until the Victorians developed the lampshade). So the first houses that were electrified tended to be those of enthusiasts like the chemist and physicist Sir William Crookes (who discovered the element thallium). He lived at 7 Kensington Park Gardens and claimed that his was the first domestic residence in Britain to have electric light installed, in 1881.

To begin with, private individuals who wanted electricity had to install their own generator and other equipment. According to a letter that Crookes wrote to the Times in June 1882, the installation of electric light cost him £300, including wiring the house and making the lamps. But there was considerable extra expense because he needed to excavate and build underground rooms for the machinery, and a special flue up to the roof to carry the fumes from the generator away. He installed about 50 lamps (very small ones by our standards). The generator was not powerful enough, however, to light all of them at once; it could only light two rooms perfectly and one partially. The generator was gas-powered and an engineer had to come in once a week to service it at a cost of 2s 6d.

It is not surprising, therefore, that few were convinced that electric light was a great new benefit. But Crookes was nothing if not a missionary for the new light source. He argued that electricity could still be cheaper than gas and candles and oil lamps, and would be much cheaper still when it could be supplied from a central power station. He also pointed out that with electricity “ceilings do not need to be blackened, the curtains are not soiled with soot and smoke, the decorative paintwork is not destroyed or the gilding tarnished, the bindings of books are not rotted, the air of the room remains cool and fresh and is not vitiated by the hot fumes of burnt or semi-burnt gas, while fire risk is almost annihilated, as no lucifers [matches] are used and the lamps are high out of reach.”

By the end of the 1880s, entrepreneurs were obtaining licences to build local power-stations to supply a whole neighbourhood (the Government having passed legislation giving licensed electricity companies the right to dig up the highway to lay cables, initiating the disruptions that still plague us today). One of the first power stations in London was the Notting Hill Electric Lighting Company, of which Sir William Crookes was a director. It was situated in the specially converted basements of a row of houses in a street called Bulmer Place which then ran between the shops on the north side of Notting Hill Gate and Ladbroke Road.

In June 1891, the new power station was ceremonially opened. 14 miles of copper cable had been laid and it was designed to light 10,000 lamps, although only 5,000 had been ordered. At the opening Crookes, who was something of a humorist, according to the Daily News, introduced “one of the company’s engineers”, a dog who was carried on to the lecturer’s table, to the delight of the audience. The dog’s job was to carry the wire cabling through the culverts below street level. When Crookes had finished his speech, Mrs Crookes turned on the current and a pattern of lamps spelled out the initials of the company N.H.E.L.C 1891.

Crookes later expressed the hope that the power station would exist for the full forty-two years of its licence. Within 10 years, however, demand was outrunning capacity and the company joined forces with another existing company to build a new and larger power station at Wood Lane. Over the years, the state began to take more control over the electricity supply. In 1947 all the electric power companies were nationalised, and Crookes’s Notting Hill Electric Lighting Company was merged into the London Electricity Board (LEB). Then in 1990 came the privatisation of the electricity industry and the LEB became the London Electricity Company plc. It was acquired by the French electricity company EDF (Electricité de France) in 1998. Throughout all these tergiversations, the site behind Ladbroke Road (which is now entered through Victoria Gardens) remained part of the assets of the succeeding concerns, used variously as a storage depot, sub-station and offices. A few years ago, EDF sold part of the site to developers as surplus to requirements, and various attempts have been made since then to build luxury housing. But the southern part of the site still belongs to EDF, who have retained it to have emergency access to the cables that are still below ground there.

Famous residents

This article was written by one of our members, Sue Cohen.

Ladbroke was a daring experiment in Cheltenham-style respectability on the edge of the abyss. Just below the white stucco villas and leafy gardens of the retired Indian Army officers, churchmen and lawyers, there flourished one of the worst slums in Victorian London. It was fifty years before the local authorities finally cleared up the shanty town, known as the Piggeries and the Potteries, where the flooded, rubbish-filled clay pits acted as open sewers.

Today two plaques reflect the (literally) sticky relationship between the ‘haves’ of Ladbroke and the ‘have-nots’. The first is in the churchyard of St John’s, at the top of the hill, where a grandstand was built for the race-course (or hippodrome) laid out on the north-west part of the estate by John White in 1837. The race-course failed after four years; the horses slipped and skidded in the clayey hollows. Worse, the course was invaded by the men from the Piggeries and Potteries who claimed a right of way to Notting Hill.

The second plaque commemorates the Potteries themselves: it is placed on the sole surviving brick kiln in Walmer Road, at the western foot of Notting Hill, which once produced the bricks and tiles for the gentlemen’s residences being built further up the hill. In the 1840s it was an area of unmitigated squalor: the average age of death there was 12 years, compared to an average of 37 for London as a whole.

There are also several blue plaques to commemorate residents, most of them distinguished artists. Perhaps because of its reputation for seediness, Ladbroke became an artistic quarter. A tall block, Lansdowne House Studios, near the junction of Lansdowne Road and Holland Park Avenue, was purpose-built by William Flockhart (1852-1913) in 1904 as artists’ studios (large north windows still face onto Ladbroke Road). The blue plaque commemorates no fewer than six artists. The painter and lithographer Charles Shannon (1863-1937) lived there with his devoted friend Charles Ricketts (1866-1931), a painter, printer and stage designer (of Oscar Wilde’s Salome in 1906 and G B Shaw’s St Joan in 1924). Ricketts owned and edited the magazine The Dial, and together they amassed a considerable art collection. Glyn Philpott RA (1884-1937) was a portrait painter and sculptor. His pupil Vivian Forbes (1891-1937) was in his youth one of the Beggarstaff Brothers (the other was William Nicholson), producing bold and innovative graphic posters. By the time he moved to the Studios he was an established painter and stage designer.

Ladbroke also housed one exceptional man of science: Sir William Crookes (1832-1919), the gifted inorganic chemist and discoverer of thallium, who lived and worked for nearly 40 years at 7 Kensington Park Gardens.

One of the more recent plaques commemorates Ladbroke’s most famous visitor. Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964), the first Prime Minister of India after Independence in 1947, stayed at 60 Elgin Crescent in his early twenties, presumably during vacations from Cambridge.

Many other local residents deserve a plaque. C H Blake, who developed Stanley Crescent, Stanley Gardens and Kensington Park Gardens north side, lived from 1854 to 1859 at 24 Kensington Park Gardens in a house designed for him by Thomas Allom. In 1872-1880 Hablot Knight Browne, who illustrated many of Dickens’s novels under the pseudonym Phiz, lived at 99 Ladbroke Grove. Sir Aston Webb (1849-1930), the architect of Admiralty Arch, the main block of the Victoria and Albert Museum and the east front of Buckingham Palace, lived from 1890 to 1930 at 1 Lansdowne Walk in a house he substantially redesigned himself.

Edmund Dulac (1882-1953), the illustrator of the exotic and fantastic, lived from 1912 to 1939 between 72 and 117 Ladbroke Road. One imagines that he must have visited his neighbours in Lansdowne House, also passionate collectors of Oriental art.

At 88 Kensington Park Road lived the Hassalls: John Hassall (1868-1948) was one of the earliest and boldest designers of advertising posters, while his daughter Joan Hassall(1906-1988) was an accomplished wood-engraver.

Osbert Lancaster (1908-1986) that acute observer of social and architectural fashion and vagaries, spent the first nine years of his life at 79 Elgin Crescent and was sent to Norland Place School. A little earlier the Russian clairvoyant, Madame Helena Blavatsky (1831-91), cofounder of the Theosophist Society, lived in the same house. Lancaster gave an entertaining account of that seedy neighbourhood In his autobiography, All Done from Memory (London, 1963), and illustrated the communal gardens of Ladbroke Square in The Pleasure Garden (London, 1977), written with his wife Anne Scott-James. A blue plaque to him on 79 Elgin Crescent was unveiled on 26 June 2015.

In 1904, at the age of 29, Edgar Wallace was on the run from his creditors. He moved into a ‘plaster-fronted Victorian house which had outlived its pretensions’ at 37 Elgin Crescent. At that date he was working on the Daily Mail. His first novel, The Four Just Men, appeared that year, and by 1908 he was able to move into grander accommodation.

Sue Cohen

Tracing the history of your house

This article by Carolyn Starren is based on a talk that she gave for the Ladbroke Association in 2009.

This can be a fascinating and rewarding study and enjoyed by all the family. All the sources listed below can be found in the Local Studies section of the Kensington Central Library. Before visiting the library, do check for any documentary sources you may have at home, e.g. deeds, land registry documents or architectural plans detailing alterations. It may also be useful to familiarise yourself with the general history of the area. An introduction can be found on the Ladbroke Association website, and histories of each street in the area are also being progressively posted on the website. Books about the area include:

• Notting Hill in Bygone Days, by Florence Gladstone, originally published in 1924 and republished in 1969 with additional material by Ashley Barker (Anne Bingley).

• Notting Hill and Holland Park Past, by Barbara Denny (Historical Publications, 1993).

• Notting Hill Behind the Scenes, by Hermione Campion, (BehindTheScenesPublishing.com, 2007) – contains many old photographs of the area.

Colin Thorn’s book Researching London’s Houses (Historical Publications 2005) is particularly recommended, as it explains in detail the purpose of and how to use the sources listed below and many others available in other repositories.

Buildings and Architecture

Survey of London

Vol. 39, Chapter 9 (pp. 194-257) of the Survey of London (published by the Greater London Council in 1973) gives a very detailed description of the development of the Ladbroke Estate, including a list of building leases with dates, developer and builder. It is also available on line at

https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol37

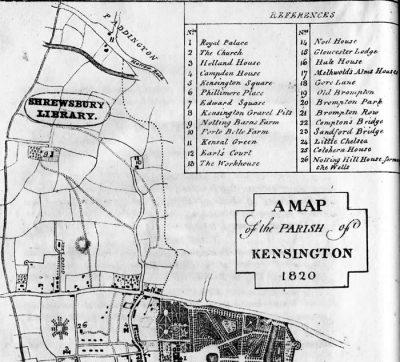

Maps

The best visual and instantly understandable resource is maps. The Local Studies section has a good collection of old maps in their map cases. Prior to 1860 parish maps are useful, as are large scale London maps such as Davies of 1841 and 1847.

The Ordnance Survey large-scale maps (5′ and 25″ to a mile) show the site, size and shape of individual houses, sometimes even garden design, and the immediate street layout. These were first produced in the 1860s and revised in 1890s, early 20th century and 1930s. Note, however, that street names and house numbering systems have sometimes changed and many streets and houses only acquired their present names and numbers in the 1860s or later. In particular, it was common in the first half of the 19th century for each terrace in a street to have its own name and numbering system. It may be easiest, therefore, to start with the 1935 Land Registry edition, which includes house numbers, and work backwards making notes of any changes to street names and alterations to the house.

Plans

The History Index in the Local Studies section, arranged alphabetically, gives references to all metropolitan and borough plans held in the archives. These include early sewer plans (from 1856); street naming and numbering plans (especially important as hours can be wasted researching the wrong house); and building applications (1872-1925). Plans can also be found attached to manuscripts and these are accessed via the manuscript index. Another useful series of plans are drainage applications which date from 1850s. Nearly every house has at least one application but coverage and detail can vary from sketch plans and outlines to detailed elevations and floor plans. They also show when a house changed from single to multi-occupancy and sometimes back to single occupancy.

Vestry records 1855-1900

These include minutes and surveyors’ returns. Exact references can be found in the Survey of London.

Deeds and manuscripts

A search of the manuscript index in the Local Studies Section will quickly show any property deeds relating to your house that are held in the archives. There is a particularly good collection of deeds relating to houses put up William Drew and Richard Roy. Although reading these deeds can be challenging in terms of both the legal jargon and the Victorian penmanship, they do contain a wealth of information, including dates of sales, terms of tenancies, purchase prices, rents, and names and addresses of owners, tenants, sellers and purchasers or mortgagees. Usually the most important parts of the document can be easily identified as the first words are written in bold and/or capitals.

Rate and valuation books

These offer an accurate record of occupiers and value of property and are an invaluable aid to tracing the history of a street and individual houses. Rates were collected twice yearly. A relatively complete set of books from the mid 18th to mid 19th century is held at the Local Studies Section. After that period quinquennial valuation books are held. The 1910 “New Domesday” books give a very detailed snapshot of properties, showing their owners and occupiers at the beginning of the 20th century

Planning records

The planning history of individual houses can be consulted on microfiche in the Planning section of the Town Hall in Hornton Street. The records mostly go back to the 1950s and sometimes to the 1930s. Many – especially the more recent ones – have been scanned and can also be consulted on the RBKC website.

Bomb incident cards

These contemporaneous warden’s reports are arranged alphabetically by street and give date of incident, type of bomb, damage caused and casualties.

Owners and occupiers

Census returns

The ten-yearly census returns for 1841-1901 are available on microfilm in the Local Studies Centre, although unfortunately the part of the 1841 census that covered the Ladbroke estate has been lost. The 1911 census has recently been released on a pay-per-search basis via the internet. The census returns give details of all members of the household, their ages, occupations and place of birth.

Directories

The most useful are the local street directories dating from the late 19th century but earlier London wide ones are available on microfilm. Court guides (directories listing the names and addresses of people of standing) are also useful for the Ladbroke area.

Electoral rolls

These are the best source of information on late 19th and early 20th century residents and are arranged by polling district and then by street. From 1890 to 1894, the Ladbroke area is divided between three polling districts: Pembridge, Ladbroke and Norland; from 1895 onwards, all the relevant streets are listed under the Pembridge and Norland polling districts.

Other sources

Illustrations

There is a large but not comprehensive collection of drawings, postcards and photographs in the Local Studies section that has been built up since 1888. Coverage of the Ladbroke area is quite good especially of postcards dating from 1902-1910. There is also a more recent photographic survey undertaken in the late 1960s to early 1970s.

The Ladbroke Association has also undertaken its own photographic survey, with photographs of every house front in the area taken between 2003 and 2008. This is on CD in the Local Studies section of Kensington Public Library..

Ephemera

Including estate agent particulars and newspaper cuttings on properties and

residents. These are filed under streets in the Local Studies section.

Carolyn Starren

March 2009

Page last updated 3.2.2015