Keeping the Ladbroke area special

Kensington Park Gardens looking towards St John’s church. PhotoBECKET 2014

Kensington Park Gardens

Introduction

Kensington Park Gardens is a broad, open street, connecting Ladbroke Grove to Kensington Park Road at the apex of Notting Hill, with a magnificent vista to St John’s church at the western end. Both sides of the street back onto communal gardens, and St John’s Church was built on its chosen site to close the vista at the west end of the street. The housing was built in the 1850s during the second great wave of construction on the Ladbroke estate. In the filthy atmosphere of London in the 19th century, a considerable premium was put on being high up, and the land on which Kensington Park Gardens now stands was amongst the most valuable on the estate. The street contains some of the most important and grandest houses in the Ladbroke area.

The original layout plan for the area and designs for the houses in Kensington Park Gardens had been drawn up by the Ladbroke family’s architect and surveyor Thomas Allason in 1849, but he died before it could be fully executed. The earliest phase of development, Nos. 1-9 (consecutive) on the south east end of the street, was most likely based on Thomas Allason’s original plans, but the final design for most of the terraced housing on Kensington Park Gardens was radically adapted by Thomas Allom, who took Allason’s place as architectural adviser to the estate.

The south side of the street consisted almost entirely of detached trios of villas, unusually for the Ladbroke estate, where terraces and pairs of semi-detached villas are the norm. All back onto Ladbroke Square Garden. The north side is an extremely grand terrace, with a magnificent archway in the centre through to the Stanley Garden South communal garden.

Architecture and history of the buildings

Old postcard of Nos. 1-9 Kensington Park Gardens c. 1900. Courtesy RBKC

Find out about the coming of electric lights to the Ladbroke area by clicking here

Development of Kensington Park Gardens on what the Survey of London (vol XXXVII, p.225) describes the ‘best land at the summit of the hill’ began in 1849/50. The earliest houses, Nos. 1-9 on the south-east side, were the result of building agreements between the estate owner, Felix Ladbroke, and W.J. Drew, the developer. The process followed was common at the time, whereby building leases were initially granted; then, once the houses had been erected, the builders were given 99-year leases at a small ground rent, enabling them to recover their outlay by letting the houses.

Nos. 1-9 were designed as three detached ‘triplex’ villas. The triplex villa design consisted of three dwellings orchestrated as a single, more monumental architectural unit. To emphasize the central entrance as the principal focus, the footprint of the centre unit is broader at the front of the property, but narrower at the rear. The side units, however, are more modest at the front, but are wider at the rear. In plan, therefore, the party walls of the triplex unit are not straight, nor perpendicular to the highway, but rather fit together like a jigsaw. The buildings have four main storeys plus basement or lower ground floor, and all have small private gardens backing directly onto the communal gardens of Ladbroke Square.

The first triplex (Nos. 1-3) is of un-rendered London brick, with bowed full height bays to either side and a double height central entrance bay topped with a bottle balustrade parapet. A double string cornice, broken by windows, presents a strong horizontal emphasis at second storey level, while a double order of stucco pilasters, each rising through two stories above and below the horizontal cornice creates the vertical interest. The façade of the building is an amplification of smaller scale designs previously executed by Drew in conjunction with Allason at Nos. 12 and 14 Clarendon Road.

1-3 Kensington Park Gardens. © Thomas Erskine 2006

The entrance to No. 1 is around the corner on Kensington Park Road, and it has a small ground floor extension at the side/rear of the property. The entrance to No. 3 is set back on the other side of the main façade so that it does not detract from the impressive central entry point of the triplex design at No. 2. The entrance to No. 2 is a wide staircase leading to a double front door at the upper ground floor level. Substantial stucco plinths to either side of the staircase originally sported reclining lions, one of which – very battered – still lingers in the front garden. To either side, a bottle balustrade with stuccoed piers sweeps in a dramatic semi-circle from the plinths to the front boundary. The bottle balustrade detail is picked up on the balcony parapet above the central entrance and also at the ground floor front windows of Nos. 1 and 3.

The three triplexes all had bottle balustrades along their street boundaries, although parts of these have been lost on Nos. 3,4 and 9. These balustrades have a different style to those on the other houses on this side of the street, with cushion-topped pillars rising slightly above the balustrade (rather than being flush with the balustrade). Nos. 3, 4, 6 and 7 have higher pillars either side of their entrances. These probably once had gates between them, as there are the remains of fixtures on some of the pillars, and handsome new gates were installed in 2013.

The rear elevations facing onto Ladbroke Square Garden are similarly detailed with single stucco pilasters.

Rear elevation Nos. 3, 2, 1

From the 1950s until his death in 1997, No. 1 Kensington Park Gardens was the home of a rich eccentric called Michael Howard. He lived there with a cook and a housekeeper, and allowed a number of less well-off relatives and friends to share the house with him, making often only modest contributions towards the outgoings. He regarded them as his family and, while the occupants usually had their own bed-sitting rooms, there was a considerable degree of communal living.

The other two triplex villas, Nos. 4-6 and Nos. 7-9 Kensington Park Gardens (with the exception of No. 5), are more Italianate in manner, while retaining an echo of the double pilasters favoured by Drew and/or Allason on the upper storeys. These two villas also share the jigsaw triplex plan, with emphasis upon the central unit at the front (still clearly visible at No. 8) with a wide staircase, double storey central bay topped with a balustrade balcony and sweeping bottle balustrade boundary wall, all of which relate directly to the villa at Nos. 1-3.

7-9 Kensington Park Gardens. PhotoBECKET 2014

Yet, despite these common design elements, the appearance of these two triplex villas was and still is quite different from the more restrained triplex villa at Nos. 1-3: Their uniformly stuccoed facades have more complex fenestration and considerably more surface detail in the form of cornicing and corbelling interspersed with rosettes. Both triplex villas would originally have had corbelled string cornices between the 2nd and 3rd floors as well as at roof level, and were originally topped with bottle balustrade parapet walls. Now, both corbelled string course and bottle balustrade are missing from No. 9. The symmetry of the villa facade at Nos. 7-9 is further compromised by the recessed entry at No. 7 having been replaced by a full height extra bay, artificially widening the flanking bay. The addition of an incongruously elaborate entrance to No. 7 interrupts the rhythm of the complex, detracting by its lopsidedness from the triplex villa’s central focus at No. 8. This addition is already there in the photograph above, taken c.1900, so it dates from the 19th century.

As with most mid-19th century buildings, there have been many other additions and alterations to the original designs. Nos. 4, 7 and 8 all have roof extensions, although the mansard roof at No. 4 is the only extension clearly visible from the street. The roof extensions on Nos. 7 and 8, however, The fact that both Nos. 7 and 8 have roof extensions, and have lowered the sills of their attic storey windows, makes No. 9 now look oddly out-of-step when seen from Ladbroke Square, even though it is in fact more ‘original’ than its neighbours. Both Nos. 4 and 7 have installed lift shafts which extend above the roof lines and are highly visible on the rear elevations facing the communal gardens. No. 4 in particular has undergone considerable modification, with a massive development of the rear garden spanning the width of the property to the rear boundary, highly visible from the communal garden itself. Of the five remaining units in this Italianate style (Nos 4, 6 ,7, 8,and 9), No. 6 retains the most of the original decorative stucco features.

At the triplex villa Nos. 4-6, the original central unit No. 5 Kensington Park Gardens was demolished (possibly after a fire) and replaced in a completely different architectural style, destroying the focal logic of the triplex villa. The rebuilding took place around 1901 (a 99-year lease was granted in 1902). This was a period when mansion flats with their lateral living pattern were all the mode, and no doubt the destruction of the old building was seen as a good opportunity to provide such accommodation here. According to a 1913 agent’s flyer (in Kensington Public Library) the building had a uniformed porter and both an “Electric Passenger Lift” and a “Trades Lift”. The basement contained coal cellars and storage spaces for the flats.

No. 4 No. 5 No. 6 PhotoBECKET 2014

Although the jigsaw footprint of the unit remains, everything else about No. 5 is different. There are seven stories rather than five (with one flat per floor), resulting in different and less generous vertical proportions. The architectural design, referred to dismissively by the Survey of London as ‘obtrusive (red) brick and terra-cotta’, bears no relationship to the original and/or surrounding architecture. Indeed, it appears designed to stand out dramatically from the rest of street. It is known locally as ‘Little Harrods,’ sharing its creative inspiration with that Knightsbridge institution, although the architect was not the same – it was designed by W. J. Worley, who also designed similar blocks at 34-35 Kensington Court; 40 Hyde Park Gate; Albert Court in Prince Consort Road; and 41 Harley Street.

Taken as a building in its own right, No. 5 has a certain exuberant charm; there are a variety of gothic details on the front facade including leaded window panes and mullioned windows, a three storey curved bay (from level 2 to level 5) and an off-set three storey Victorian bay (from level 5 to level 7) crowned with an octagonal turret. There is also quarter turret at upper ground floor level and colourful chimneys both sides. The magnificent central entrance of the original building has been replaced with an insignificant staircase (at the left in the picture) providing access to the upper floors, and the sweeping balustrade boundary wall has been removed completely and a make-shift metal railing erected in its place. An unfortunate wooden dormer at roof level on the front facade is a later addition (planning permission was granted in the 1960s).

When looking at the rear elevation, the contrast with the adjacent classical buildings is especially stark. Following the jigsaw footprint of the original central unit – wider at the front and narrower at the rear – No. 5 is brutally vertical in appearance, towering above neighbouring houses, with two semi-circular side-by-side bays, stretching from the ground to the roofline. The effect is accentuated by the not entirely successful extra floor that has been added at the back.

Rear elevation of Nos. 6, 5, 4

There is a wrought iron gate into the communal garden between Nos. 9 and 10, decorated with the coat of arms of Felix Ladbroke.

The small front gardens of these triplexes were all originally separated from the street by handsome bottle balustrades. These balustrades have a different style to those on the other houses on this side of the street, with cushion-topped piers rising slightly above the balustrade (rather than being flush with the balustrade). Nos. 3, 4, 6 and 7 have higher piers either side of their entrances. These probably originally had gates between them, as there are the remains of fixtures on some of the piers, and No. 8 has higher pillars on either side of its ironwork side gates. In 2023, new ironwork gates were installed.

At some point No. 9 had its balustrade replaced by a solid wall, which is a pity. The creation of hard standing and access for vehicles has also led to the loss of some balustrading.

The original pattern for the front area of these houses was for there to be a narrow lightwell next to the house to allow some light to the lower ground floor. In some cases, the garden has been partially or wholly dug out to create a bigger area at the lower level. Because of the bottle balustrading, this is luckily not too visible.

The private back gardens of all these villas must originally have been separated from the Ladbroke Square communal garden by bottle balustrading between similar to that which still exists at Nos. 1-2 (and also at Nos. 10-12 and 20-21). Now most of the houses have iron-work fences mounted on a low brick or rendered wall. The gardens are mostly well-planted, but a few have been marred by brick side-walls or structures in the garden.

Bottle balustrading at the back of Nos. 1-2 Kensington Park Gardens.

A blue plaque on 6 Kensington Park Gardens was installed in 2023 in honour of Michael Ibru (1930–2016), a Nigerian billionaire business magnate and philanthropist whose London home was in this house from 1974 to 2007. Despite the colour of the plaque, it is not an official English Heritage blue plaque, but was put up by the Nubian Jak Community Trust, an organisation dedicated to memorialising the historic contributions of Black and minority ethnic people in Britain.

A Blue English Heritage Plaque on No. 7 recognises the scientist Sir William Crookes, who lived here from 1880 to 1919 and was one of the pioneers of domestic electric lighting. It is believed that No. 7 was the first house in England to be lit by electricity.

No. 8 was one of the many long leaseholds that W.J. Drew acquired during his lifetime, probably when Felix Ladbroke inherited the estate in 1847 and began selling off both leaseholds and freeholds (that of No. 8 was due to expire on 24 June 1949). Drew family papers show that it was one of the holdings that Drew left to a family trust when he did in 1847. The rent payable to the trust was £300 a year, a substantial amount for the period.The trust was wound up after the death of the last named beneficiary in 1917, and the leasehold was presumably sold again.

No. 9 was the home of Sir John Evans, a distinguished Victorian archaeologist, father of Sir Arthur Evans, the excavator of Knossos, and Joan Evans, the art historian and first woman to serve as President of the Society of Antiquaries as well as the Royal Archaeological Institute. Joan, the child of her father’s third marriage and his old age, was raised in the house and recalled it fondly in her autobiography Prelude and Fugue (The Museum Press, 1964, p. 123):

The great charm of the house lay in its position. To the north it looked over a broad street; to the south it opened first onto a little garden and then, without any intervening road, on to the wide spaces of the largest square in London. In summer we could not see across to the other side. Such a setting made it small hardship to have no country house.

Listings and Article 4 Directions (Nos. 1-9) Strangely, none of these interesting triplex villas is listed. All, however, are subject to Article 4 directions removing permitted development rights in respect of:

In addition, Nos. 3-4, 6-7 and 9 are subject to Article 4 directions in respect of alterations to the side of the house. Ladbroke Square is the only communal garden on the Ladbroke estate always to have had a resident gardener with his own cottage – already shown on the 1849 plans for the garden. The Cottage (behind No. 1 Kensington Park Gardens) is also subject to an Article 4 Direction removing permitted development rights in respect of alterations to, or construction or demolition of walls, gates and fences facing the communal gardens. The gates into Ladbroke Square between Nos. 9 and 10 Kensington Park Gardens were listed Grade II in 1984. They are described in the listing as “Pair of cast iron gates. Mid-19th century. Each two panels deep, with inscribed circles in scroll borders. Shields with coat of arms of Felix Ladbroke to centre of circles”. They are also subject to an Article 4 Directive which means that planning permission must be sought for the erection, alteration or demolition of gates, fences and walls facing the highway (1998). Recommendations for new Article 4 directives (Nos. 1-9) 1. The present article 4 Directive relating to the façades relates only to front doors and windows. Protection is also needed for features such as string courses and we recommend that all alterations to the façades should be subject to planning permission (as is the case already for alterations to the sides and rears). 2. An Article 4 directive should remove permitted development rights in respect of the erection, alteration or demolition of gates, walls and railings on both sides of the path leading from Kensington Park Gardens to Ladbroke Square Gardens, as the path is an important feature of the gateway. 3. The partitions between the private gardens at the rear are important, as high opaque fencing and even worse brick walls detracts from the open leafy aspect of the private gardens that is important to the character of the communal garden. We recommend the extension of the protection of an Article 4 direction to the walls and fences between the private gardens. |

Recommendations to planners and householders (Nos. 1-9) There are a number of missing or unfortunate features that we hope that householders will one day restore or remove. In particular:

Paintwork: we recommend that stucco be painted white, cream or in a pale pastel colour. Window frames should generally be painted white or black. Railings and ironwork should generally be painted black. |

South side: 10-23 Kensington Park Gardens

Nos. 10-22 (consecutive) and 24-47 (consecutive) Kensington Park Gardens were designed by Thomas Allom (1804-1872), the great architectural adviser to the Ladbroke estate. Thomas Allom was a combination of valuer, surveyor and architect. The concept of an architectural profession was a newish one and he was a founder member of the Royal Institute of British Architects (R.I.B.A). He was also an artist in his own right as well as a theatrical designer. His early reputation was made as a landscape painter and his architectural designs appear to be influenced by his artistic vision. As the Survey of London (vol XXXVII, p.229) puts it:

It says much for Allom’s brilliant scenic display that his strange sort of grandeur is still evident in spite of all the damage that the twentieth century has done. He adopted a more flexible, more romantic approach than the architects of South Kensington or Bayswater. His skill was to make use of the terrace ends, the junctions and the curves in the street, to introduce special emphasis with great bowed projections, turrets, columnar screens and houses of curious plan forms.

Thomas Allom was at the height of his architectural creativity when he began work for the Ladbroke Estate. He was particularly interested in vistas: strategically positioned gaps between houses affording glimpses of the gardens within (most of which have been lost in the intervening years) and churches positioned so they could be seen at the ends of streets. Allom theatrically aligned the impressive northern entrance to Ladbroke Square Garden (between Nos. 9 &10 Kensington Park Gardens) with the equally dramatic Roman arch over the southern entrance to Stanley Gardens opposite (connecting Nos. 34 & 35 Kensington Park Gardens). Pedestrians were treated with glimpses trees, highly decorative architecture, and a dramatic and inspiring view of St. Johns’ at the end of the street. Allom made a speciality of elegant design solutions to terrace ends and junctions, which few architects have bettered over the years.

Nos. 10-22 Kensington Park Gardens showcase Thomas Allom’s dramatic vision and artistic flair. Essentially, the houses are four storeys above a basement level with wide frontages in excess of thirty feet. The range is a complex study in terrace articulation, arranged in a complicated but symmetrical fashion.

Old postcard of the south side of Kensington Park Gardens with Nos. 20-22 in the foreground, c. 1910. Courtesy RBKC

The original 1852 building lease for these houses given by Felix Ladbroke to David Allan Ramsay, a nurseryman turned builder, survives in the local studies section of Kensington Public Library (deed No. 4594). It required Ramsay to erect “thirteen good and substantial brick messuages or dwelling houses in five alternate blocks of three and two houses”, following the plans provided by Ladbroke. The houses had to be of a value of at least £1,500 (a good sum for the times) and Ramsay undertook to ensure that the occupants would not engage in noisome trades or hang clothes out to dry in the gardens. Ladbroke for his part undertook that the occupants would be given access to “the Ornamental Garden or Pleasure Ground called Ladbroke Square, for the purpose of resorting thereto for pleasure”. They had, however, to conform to such rules and regulations as might be laid down by Ladbroke or his successors, or by any committee of the residents. They could take family and friends into the pleasure garden, but such people were not allowed in unaccompanied (later, the leases for the individual houses specified an annual payment of three guineas for use of the garden).

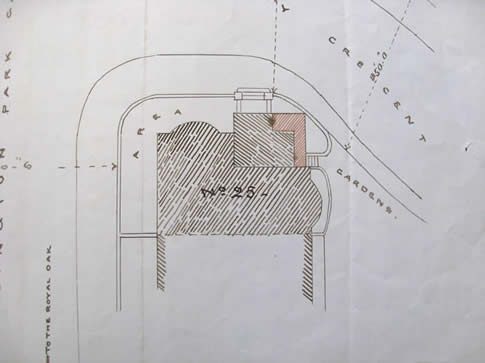

Plan from the 1852 deed showing where the houses were to be built.

The result was a terrace consisting of five building groups, with each group linked only by entry porches at ground level with double Doric columns on either side. Above these porticos were gaps between the buildings providing tantalising glimpses of the trees and gardens in Ladbroke Square Garden beyond. Over the years, roof extensions have been added (Nos.16 & 17), decorative detail removed, and most unfortunate of all for the integrity of the terrace concept, side extensions have been built over the linked porches, filling in the gaps between the building groups and rendering the overall appearance of the terrace more conventionally continuous and flat-fronted. Not only has this eliminated the intended vistas, but these additions and mutilations make the articulation more difficult to analyse. Basically the front façade rhythm, suggested by the Survey of London (vol XXXVII, p. 229) is:

ABA – AA – AB*A – AA – ABA

The first group (Nos. 10, 11, 12) consists of three units with the A units on either side set slightly forward of the central B unit, and defined by rusticated corner stucco decoration extending to the string cornice at the 2ndfloor level. Thomas Allom’s playful use of classical detail is on full display here: the ground floor level is rusticated with round topped windows and porticos with Doric columns; The piano nobile has full length windows opening onto a narrow front balcony with curved wrought iron railings. At the first floor of the A units, there are double Corinthian pilasters supporting a decorative entablature, above which at the second floor level, is a faux balcony with a distinctive Allom balustrade motif and a central projecting balcony terrace. Encompassing all three balcony windows is a projecting moulding which renders the whole suggestive of a Venetian window enclosure. The prominent corbelled string cornice between the 2nd and 3rdfloor levels is a defining feature of the terrace, emphasizing the importance of the lower floors, and reducing the stature of the third floor, attic storey. At the attic level, there are plain pilasters at the corners, a plain less prominent cornice at roof level, and stucco architrave detail around the windows.

The central B type unit differs somewhat in detail: there are triangular window pediments above the central window on the 2nd floor, and above the side windows on the first floor. At the rusticated ground level, the B unit has a series of four double Doric columns suggesting a shallow portico framing the entry and ground floor windows with a wide entablature across the entire width of the building. This shallow portico projects in front of and overlaps the A units on either side, tying the three together into a single unit. Between Nos. 12 and 13, the gap has been only partially been filled in above the entry porches, making it possible to still imagine the effect envisioned by the architect. This is therefore a particularly important gap. The side elevation of No. 12 also deserves special notice with its decorative stucco window treatments.

Nos. 10-12 Kensington Park Gardens. PhotoBECKET 2014

Originally, the second group, Nos. 13 and 14, consisted of two A units followed by a gap, then a third group of three units AB*A. The third group (Nos. 15, 16 and 17) forms the centrepiece of the terrace, marked by the fact that B* is slightly different to the B of the other groups. Otherwise it is similar to the first ABA group as regards the front facade, although differently articulated at the rear. The fourth group repeats the second group (AA) and the fifth group repeats the first group (ABA). The terrace, therefore, has a gentle symmetry of 3-2-3-2-3, disguised by the infilling of the most of the gaps.

The infilling of the gap between Nos. 14 and 15 has particularly blurred the integrity of the terrace articulation. It has been done in such a way that the attic storeys of Nos. 13-15 appear contiguous, binding two building groups together. The mind’s eye is more likely to conclude that a bit of string cornice is missing, rather than that a chunk of building has been added.

Nos. 13 & 14 (AA) Nos. 15, 16, 17 (AB*A) PhotoBECKET 2014

A 1949 deed (No. 11319) Local Studies centre of Kensington Public Library gives a list of the rooms on each floor of No. 14 in the days of Lord Broughshane, who was the M.P. for Kensington 1919-1945:

- Basement: kitchen; linen room; butler’s pantry; scullery; external cellars.

- Ground floor: entrance hall; library; dining room.

- First floor: No. 1 bedroom; No. 2 bedroom; drawing room.

- Second floor: Lord Broughshane’s bedroom; bathroom; Lady Broughshane’s bedroom; spare room.

- Third floor: front left room; bathroom (front); front room; small room rear; large room rear.

On the other side of the central AB*A group (Nos. 15, 16, 17) the infilling of the gaps between Nos. 17 and 18, and between 19 and 20 has stopped short of the attic storey, leaving a suggestion of the original gaps between the building groups.

No.17 (A) No.18, 19 (AA) No.20 (A) PhotoBECKET 2014

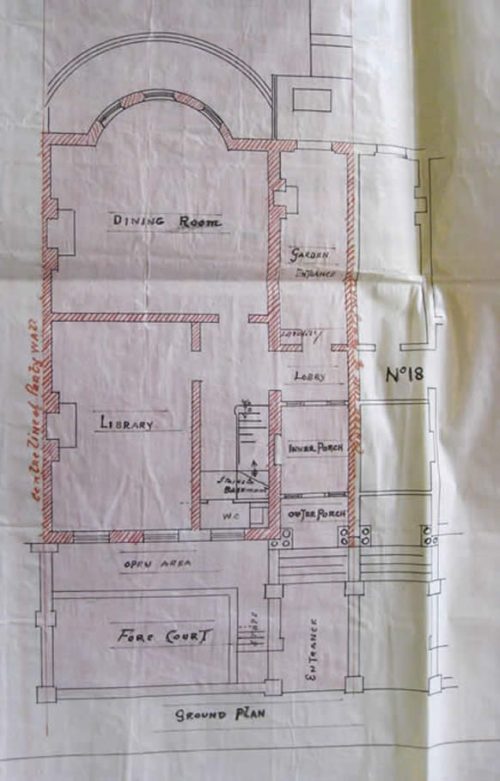

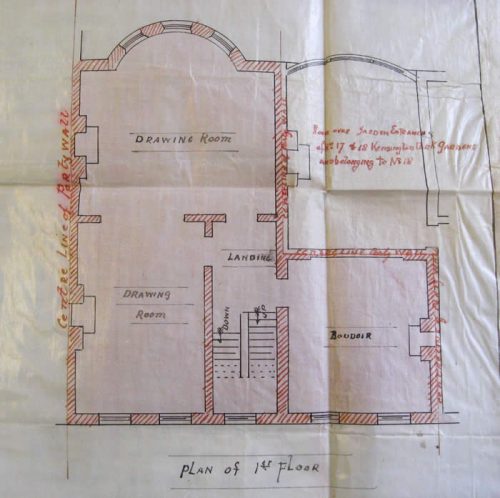

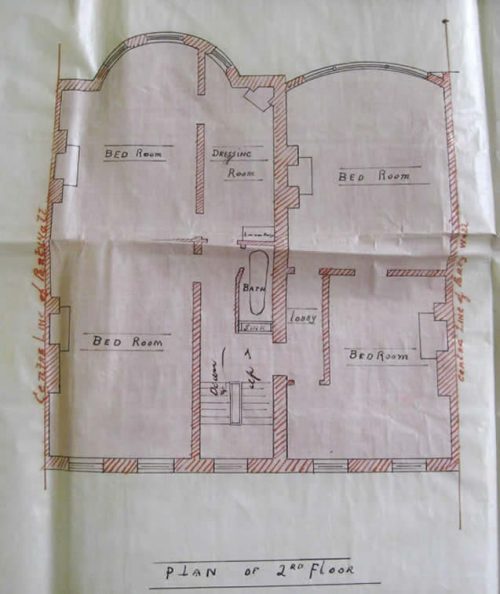

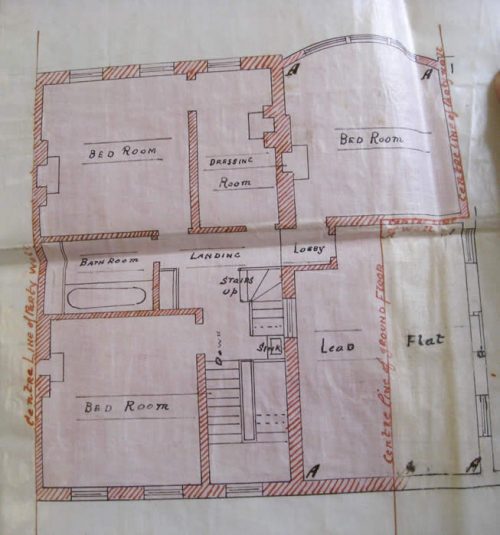

Some of the infilling is very ancient. A deed in Kensington Public Library (deed No. 6125) dating from 1883 (when the freehold was sold for £1500) indicates that a three floor infill between Nos. 17 and 18 had already been built (the third floor only at the back), part of it for the use of No. 17 and part for the use of No. 18, with covenants between the two owners allowing for such use – see the plans below.

Ground floor plan of 17 Kensington Park Road in 1883

First floor plan of No. 17 in 1883

Second floor plan of No. 17 in 1883

Third floor plan of No. 17 in 1883

In the 150 years these houses have been in occupation, there have been many other alterations and mutilations. The area has not always been as affluent as it has become in recent decades, and many decorative features have been removed or altered along the way. Both Nos. 16 and 17 have had additional storeys added which vertically disrupt the gentle rhythm of the terrace (again, judging by the photograph above, these date from the 19th century).. Especially noticeable are the missing corbelled string cornice on Nos. 12, 17, 18 and 22. On the later three properties the cornice has been removed to allow the windows on the attic storey to be lowered and enlarged, thus making restoration virtually impossible.

The small front gardens are all separated from the street by stucco bottle balustrades.

Rear Elevations of Nos. 10 – 22 Kensington Park Gardens

Fundamental to the appeal of this terrace, as to many other parts of the Ladbroke estate, is its position backing onto a communal pleasure garden; in this case the largest such garden in London. All the buildings on the south side of Kensington Park Gardens have small private gardens with low decorative railings or plaster bottle balustrades through which there is direct access to the communal garden beyond. On the garden side is a wide gravelled broadwalk with flower borders divided by short paths leading to the gates of the private houses. Thomas Allom took full advantage of this opportunity to make the rear facades even more elaborately dramatic and decorative than the street elevations. The rear terrace undulates with rounded bays articulated to varying heights, topped by ornate balconies, parapets and railings. It exemplifies the overall richness of detail which the Victorians admired so much, and which added/adds considerably to both construction costs and subsequent maintenance costs of the buildings. The articulation of the rear terrace façade has a somewhat stronger emphasis upon the central building group than was evident on the front elevation:

ABA – AA – A*B*A* – AA – ABA

The side (type A) units are set back slightly from the central B unit, and have rounded bays extending from the lower ground to the first floor, topped by a terrace at the second floor level. A projecting moulding spanning the three windows which look out over the terrace, suggests the Venetian window enclosure encountered on the front façade. In the central, type B unit, the rounded bay reaches up to the 2nd floor.

Garden elevations of Nos. 22, 21, and 20 Kensington Park Gardens (ABA)

On the first floor are three full height windows framed by Corinthian pilasters and opening onto a narrow, semi-circular balcony with ornate curved metal railings. The pilasters support a decorative stucco entablature, which in turn is topped by an ornate parapet wall, bearing the signature design already mentioned on the front elevations. These details repeat the decorative motifs found on the front façade now translated onto a rounded bay. It is clear from the photo, that the corbelled string cornice originally wrapped around from front to the side elevation and most likely extended across the full width of the rear elevations as well on the ABA and AA groups. The remnants of the corbelled string cornice can still be seen at the corners of the units, although enlargement of attic level windows on most units has largely eliminated it.

The rear façade of the central group (A*B*A*) is distinguished by the semi-circular bays reaching to the second floor and being topped by the prominent corbelled cornice stretching across all three units. This feature begins as a string cornice but, as it encases the semi-circular bays, it becomes the parapet wall for a balcony at the attic level.

Nos. 16 & 15 (B*A) Nos. 14 & 13 (AA)

This projecting cornice is somewhat confusingly expressed on the rear elevation of this central group of buildings. The string cornice on the front facades of all the building groups, including the central group is consistent at the same level. And despite the complete absence of the string cornice on the rear elevation of the adjacent AA group (Nos. 14 & 13), there is just enough of the original detail visible on the right hand edge of No.13 (see photo) to see that the string cornice wrapping around from the front facade would have been higher than the cornice topping the 2nd floor bays on the central A*B*A* units. This curious discrepancy seems to reflect the difficulty caused by the flat roofs of the semi-circular bays also serving as terraces to the third floor apartments, which only occurs on the central A*B*A* units. With the side elevations of the central group now obscured, we may never know how the architect intended to resolve the different cornice heights.

Nos. 12,11,10 rear elevations

A number of things have been added and/or removed from the rear elevations over the years, which degenerate the original concept. As before mentioned, additional storeys and side extensions infilling original gaps are the most distracting. Some of the infilled extensions have used inappropriate fenestration out-of-keeping with the main buildings. In a few cases, the original sash windows have been replaced with modern casement windows at the third floor level (Nos. 12,11,10), and where sashes have been replaced on lower floors, some beading detail has been lost.

Rear Boundaries: Originally the boundary walls separating the private gardens from the communal garden would have been low bottle balustrade walls with wrought iron gates. Many still exist and all are now covered by the Grade II listing of the Allom terrace. Maintaining these boundary walls is the responsibility of the individual property owners.

No. 23 Kensington Park Gardens: ‘The Lodge’ is a 20th century purpose-built block of flats occupying the corner at the junction of Kensington Park Gardens and Ladbroke Grove. The dignified neo-classical building of brick and sandstone dates from the 1930s. It was designed by the architects J. Stanley Beard and Bennett and built by Ellis (Kensington) Ltd, engineers. It was built on a double plot where formerly stood a pair of semi-detached late Victorian villas, Nos. 23 and 24 Kensington Park Gardens. It is an historical mystery why this plot was not developed at the same time and by the same developer as the Thomas Allom terrace next door.

The proposed demolition and replacement of the original houses in 1936 aroused considerable local controversy, as was recorded in the columns of The Times. A number of local residents, including the publisher Victor Gollancz, the painter (and famous opponent of modern art) Frank L. Emanuel and the ex-editor of the Times and historian Henry Wickham Steed, organised a petition to the London County Council (the Times, 10.1.1936). It cited “The disfigurement caused many years ago by the erection towards the other end of this road of a single inharmonious block of flats [presumably No. 5] sharpens our desire to prevent recurrent desecration”. The architects responded in a letter to The Times, claiming that the two house were detached from the rest of the Allom-designed street and “somewhat mean in appearance.”

The photograph below from The Architect and Building News of 31.1.1936 shows what the rears of the houses looked like. They appear to have been a storey lower than their neighbours and in a later style. The entrance to No. 24 was in Ladbroke Grove.

Today the Lodge address is No. 23, although it is sometimes referred to as No. 24 in various archive plans and even in an Article 4 Direction relating to the property. Nowadays, however, No. 24 is the address of the house first house on the opposite (north) side of the road.

The Lodge at 23 Kensington Park Gardens. © Thomas Erskine 2006

Deeds (Nos. 10-23)

There are a number of 19th and early 20th century deeds (leases, mortgages and conveyances) relating to Nos. 14, 17, 18, 19 and 21 Kensington Park Road in the Local Studies section of Kensington Public Library. The voluminous papers relating to the planning permission for the Lodge are in the London Metropolitan Archives (ref: GLC/AR/BR/06/077522).

|

Listings and Article 4 Directions (Nos. 10-23) 10-22 Kensington Park Gardens are all Grade II listed, which covers alterations to external facades (front, side, and rear), windows, roofs and rooflines, lightwells, boundary walls and railings, as well as to the interior. Any work on these structures requires both Planning Permission and Listed Building Consent. The English Heritage description reads:

No. 23 (The Lodge) is subject to Article 4 Directions (in one case mistakenly referring to it as No. 24) removing permitted development rights in respect of:

|

|

Recommendations to planners and householders (Nos. 10-13) Most of the major structural alterations to Thomas Allom’s original terrace concept must now be considered permanent and irreversible, e.g. the additional stories at Nos. 16 and17: the infilling of original gaps between building groups (Nos. 14/15, 17/18, 19/10 and partial infill at 12/13); and the removal of the prominent corbelled cornice between the 2nd and 3rd floors to allow enlargement of 3rd floor windows on the front elevations of Nos. 17 and 22 and most rear elevations. However, some lost surface decoration could be re-instated with good effect for the visual continuity of whole of the terrace. We hope that owners undertaking substantial renovation projects might consider the following:

|

North side: Nos. 24-33 (consecutive)

Old postcard of the north side of Kensington Park Gardens, with No. 24 in the foreground. Courtesy RBKC

The houses on the north side were also designed by Thomas Allom. They consist of a single large house (No. 24) between Ladbroke Grove and Stanley Crescent; and a long terrace the length of the rest of the street, broken only by a central arch. The terrace backs onto the Stanley Gardens South communal garden.

Nos. 24 and 25

The past numbering of these two houses is somewhat confusing. Originally, No. 24 was No. 34 Ladbroke Grove, and No. 25 was No. 23 Kensington Park Gardens. However, when two houses were built on the site of what is now the Lodge, these were numbered 23 and 24, and the old No. 23 on the corner of Stanley Gardens became No. 25. Then, in 1897, for some reason, it was decided to make No. 34 Ladbroke Grove part of Kensington Park Gardens and it was given the number 24a Kensington Park Gardens. In 1936, after the demolition of nos. 23 and 24 and their replacement by the Lodge, the latter became No. 23, and No. 24a became simply No. 24.

No. 24 Kensington Park Gardens (the old 34 Ladbroke Grove) was designed by Allom for the principal developer of this part of the Ladbroke Estate, Charles H. Blake, who lived there from 1854 to 1859, when he was in such financial difficulty that he had to downsize by moving to a house in Stanley Gardens. No. 24 was arguably the best house in the best position on the Ladbroke estate with (in those days) far-reaching views. It admirably displays Thomas Allom’s talents as an architect, presenting an impressive double fronted elevation facing Kensington Park Gardens with attractive side extensions at ground and first floor levels providing access to the communal garden beyond. The house backs onto the side of No. 36 Ladbroke Grove. The side elevation of No. 24 masquerades as a front elevation of one end of a four unit terrace facing Ladbroke Grove: a simple yet elegant example of Allom’s corner solutions. The depth of the house is the same as the width of the front elevation of the Ladbroke Grove terraces, and it is consequently relatively shallow front to back. The semi-circular bays on either side of the double Doric entry columns are remarkably similar to the rear garden elevations of the ‘A’ units in the Allom terrace opposite. There are a few differences in the detail, but the rusticated ground floor with arched windows and the dominant corbelled cornice between the 2nd and 3rdfloors clearly tie this building closely to the surrounding terraces.

In 1988 Syracuse University established a London campus at No. 24, where they stayed for 25 years before moving to their present headquarters in Bloomsbury.

No 24 Kensington Park Gardens (front elevation on Kensington Park Gardens) © Thomas Erskine 2006

40, 38, 36 Ladbroke Grove: – the side elevation of No. 24 Kensington Park Gardens is on the right.

No. 25 Kensington Park Gardens is on the other side of Stanley Crescent, on the end of the great northern terrace. It provides another example of individual end-of-terrace architecture. Here Allom has placed the double fronted facade around the corner facing Stanley Crescent, and repeated the conceit of identifying the side elevation as a front elevation facing Kensington Park Gardens. The dominant corbelled string cornice at 2nd floor level, the rusticated ground floor motif, the narrow 1st floor balconies all stretch around the corner, tying the building unit to the terrace. The front façade, however, has two unequal bays, one semi-circular and one square, the latter the enlarged by an 1860s addition (see plan below: the part in red is the addition). The rounded windows found elsewhere in the terrace only at the rusticated ground floor level, here appear at the first floor. The overall effect is less symmetrical than the rest of the terrace, but certainly dramatic and pleasing.

Front and side elevations No. 25 photoBECKET 2014

Plan from an 1862 planning application for an extension to No. 25 (deed No. 2402, Kensington Public Library.

North side: Nos. 26-33 Kensington Park Gardens: general

The terrace that occupies the remainder of the north side of Kensington Park Gardens is divided into two parts by the dramatic Roman archway, between Nos. 33 and 34, leading to the Stanley Garden South communal garden. Apart from this grand garden entrance, there are no gaps in the articulation of the terrace. Although somewhat less decorative than the houses on the south side, the basic ingredients are the same: four stories plus basement; dominant corbelled string cornice above 2nd floor; narrow 1st floor balconies with curved wrought iron railings; and rusticated ground floor level. It is remarkable that the first floor balcony railings, which are continuous across the entire terrace, have survived almost entirely intact, with only a single exception (see below). The railing design is distinctive to this terrace, and differs somewhat from the railings on the south side of the street, and elsewhere in the Ladbroke Estate.

A wonderful feature of the north terrace is its porticoes, which sit near the pavement with a small basement areaway surrounded by balustrade boundary walls with wrought iron gates. The porticoes – sometimes single, occasionally double – present a syncopated rhythm of columns and balustrades. In the early morning with sun streaming sideways down the street, the sight is reminiscent of a piano keyboard in starkly contrasting shadow and light.

photoBECKET 2014

Porticoes

Balcony railing

Front gates

North side: Nos. 26 – 33 Kensington Park Gardens: detail

The articulation of this part of the terrace is still quite clearly visible. Discounting the end unit (the side elevation of No. 25) which in this case is not part of the pattern, the terrace is articulated as follows:

A1 A2, B2 B2 B1 B1, A1 Ax2

No.25(side) No. 26 photoBECKET 2014

Type A1 is a left-hand entry/hall plan, while A2 is a right-hand entry/hall plan. The principal distinctions of the A type units are:-

- Their front elevation sits slightly in advance of the B units, with rusticated corner decoration to the second floor emphasizing their prominence

- The third storey attic elevations are vertically in the same plane as the lower floors

- They have rounded windows at the rusticated ground floor level

A units have a projecting moulding at the first floor level, spanning the three full height windows with a semi-circular emphasis over the central window. This detail, suggesting the profile of a Venetian window reflects the same motif on the terrace opposite. There are decorative double pilasters between the windows with Corinthian capitals. The three windows of the second floor have stucco architraves with prominent mouldings above and projecting sill details with corbel supports beneath each window. On the third floor, the three windows have slightly rounded tops to the stucco architraves with a ‘key stone’ motif at the apex. There are pilasters between the windows above the string cornice.

Type B1 is a left-hand entry/hall plan, while B2 is a right-hand entry/hall plan.

The principal distinctions of the B type units are:-

- The front elevation sits slightly back from the A units

- The stucco detailing is less extensive, with flat projecting mouldings above the first floor full length windows, and no pilasters between the windows

- The attic storey is a mansard roof set back behind a low parapet wall with three dormers aligned with the fenestration lower down. This makes the unit appear lower than the neighbouring A units and increases the sense of rhythm in the terrace.

- B units have a single large triple sash window on the rusticated ground floor.

In this part of the north terrace, relatively few architectural features have been removed, added or defaced. The third floor of No. 28‘s elevation has been altered from its original A type mansard roof line to a B type façade, obscuring the 2/4/2 rhythm; No. 29 has added a front bay extension on the ground floor, bringing the window forward to the level of the first floor balcony above; the prominent corbelled string cornice has been removed from the front, side and rear elevations of No. 33, and a full height side extension has been added over the entrance at No. 33, with a window at first floor level in a style that sits strangely with the rest of the building. There is also a somewhat unfortunate hut-like back extension. In addition, the bottle balustrades and the front boundary have been replaced with railings (the houses on the north side do not have front gardens, but sunken yards behind the stucco bottle balustrades, reached through wrought iron gates and steps down from street level).

The rears of Nos. 25-33 give into the communal garden of Stanley Gardens South. The rear elevation of No. 25 in particular is as decorative as its two façades, with full stucco and a four storey semi-circular bay. The other houses are also full stucco with appropriate decorative features round the windows. The corbelled string course on the front of the houses continues round to the rear; and there is a continuous wrought iron balcony. Unfortunately the rears are not as unspoilt as the fronts. A variety of protruding bays and conservatories (many built long ago) have been added, breaking the original line. And an extra dormer floor has been allowed on the rear of No. 32 – an example of the planners ignoring the need for conserving the features on rear elevations facing communal gardens.

No. 31 Kensington Park Gardens was the home of Arthur and Sylvia Llewelyn Davies and their five sons, most remembered for their connection to J.M. Barrie and as the inspiration for the Darling family in Barrie’s famous tale, Peter Pan. Sylvia Llewelyn Davies was the daughter of George Du Maurier and aunt of author Daphne Du Maurier.

North side: Roman Arch connecting Nos. 33 and 34

The A type units on either side of the garden entrance are unique within the north terrace, with their portico entries being at the side, reflecting the design motif of the south terrace. Originally there would have been no side extensions built above the porticos and the gap in the terrace would have been much wider. The visual combination of the porticos on either side with the roman arch between would have been presented a tableau something akin to a monumental gateway.

The Roman arch. Photo 2008

North side: Nos. 34 – 47 Kensington Park Gardens

Old postcard of rthe north side of Kensington Park Gardens with Nos. 34-36 in the foreground. Courtesy RBKC

This long articulated terrace of fourteen units runs from the Roman arch to Kensington Park Road. It is less easy to read than the western end and may have undergone some alteration of design at the time of building. Conceptually, the design articulation is an extension of that seen at the eastern end:-

AA, BBBB,AA AA, BBBB,AA,BBBB, CC (corner units)

(eastern end) (western end)

The first eight units repeat the articulation of the eastern end of the terrace with only a few later additions: a roof extension at No. 34 dates from the 19th century judging by the photograph below; an extra floor on the type A unit at No. 40; and an additional floor on the paired type A unit at No. 41, although oddly, the format is that of the set-back mansard attic roof with dormers typical of the type B units.

Nos. 34 – 43 (photoBECKET 2014)

The second group of four type B units (Nos. 42-45) follows, but with one distinct difference – these units all have an extra floor. The third floor is flush with the front elevation and identical in detail to the third floor of the A units, complete with curved windows decorated by a keystone motif and with plain pilasters between the windows. On top of the third floor is an attic storey with the set-back mansard roof typical of previous B type units. The consistency of this design alteration and the uniform way in which it is expressed across all four B units at this part of the terrace suggests it is original, i.e. introduced when the units were built and not added later. The decision may have been the result of the perennial struggle between the architect’s aesthetic vision and the commercial dictates of the developer, who simply wanted more space. Whatever the reason, the architect’s vision is somewhat blurred as a result.

Nos. 36 – 46 (photoBECKET 2014)

A further odd deviation from the previous established pattern is the fact that No.44 has a right-hand, rather than a left-hand entry plan, thus disrupting the rhythm of the B unit porticos so that the double portico comes in a different place. The actual articulation of this part of the north terrace is:-

A1,A2,B2,B2,B1,B1,A1,A2,Bx2,Bx2,Bx2,Bx1, C,C

The end two units, Nos. 46 and 47 are unique end-of-terrace units with their entrances around the corner on Kensington Park Road. The extra height added to the adjacent B type units has the consequence that they tower above the end units which thereby lose some of their dramatic stature. Because No. 46 cannot be extended to the rear – No. 47 sitting immediately behind it – it has been given a wider side elevation on Kensington Park Gardens, with semi-circular bays on both this elevation and on the front facade facing Kensington Park Road. A number of blank window embrasures define a somewhat less elegant design solution than either Nos. 24 or 25.

photoBECKET 2014

These houses, like those on the other side of the arch, have no gardens but only areas level with the lower ground floor, separated from the street by stucco bottle balustrades. Unfortunately, the bottle balustrades on several of the houses have at some point been replaced by solid stucco walls or railings.

Rears of Nos. 34-47

The rears of Nos. 25-47 give onto the communal garden of Stanley Gardens South. The rear elevation of No. 25 in particular is as decorative as its two façades, with full stucco and a four storey semi-circular bay. The rear elevations of the other houses are also full stucco with appropriate decorative features round the windows. The corbelled string course on the front of the houses continues round to the rear; and there is a continuous wrought iron balcony. Unfortunately the rears are not as unspoilt as the fronts. A variety of protruding bays and conservatories (many built long ago and not in themselves unattractive) have been added at ground and first floor level, breaking the original line. And as mentioned above an extra dormer floor has been allowed on the rear of No. 33 – an example of the planners ignoring the need for conserving the features on rear elevations facing communal gardens.

As for the western end of the terrace, the houses are fully stuccoed on their rear elevations and have string courses, decoration round the windows and ironwork similar to those on the front. Again they have over the years acquired conservatories and other protrusions at ground and first floor level, some not unattractive, albeit hardly in keeping with the classical style. As in the front, there were stucco bottle balustrades between the communal garden and the lightwells of the houses. Now many of these have been lost and replaced by railings.

North side: Coal hole covers

When these houses were built mid 19th Century, coal was the primary energy source. Three local ironworks in particular appear to have provided most of the covers on the street and good examples remain on the north side.

Nos.27,28,33,36,38, 41,43,44

R.H. & J. Pearson’s

Notting Hill Gate

Patent Automatic Action

Nos.33,35,39,42

JAS Bartle & Co

Western Iron Works

Notting Hill

Bird’s Patent Self Fastening Plate

Nos. 29,30,31,34,37

J.W. Carpenter Ltd.

188-190 Earl’s Court Rd. SW

photoBECKET 2014

Deeds

There is a fairly complete selection of early deeds relating to No. 44 in the Local studies section of Kensington Public Library. These illustrate the typical transactions that followed the building of these houses. Most of the people involved in the transactions lived elsewhere (although often close by) and acquired the property for investment purposes, sub-letting it for income.

44 Kensington Park Gardens 1853: Charles Blake (one of the principal developers involved in the Ladbroke estate) and David Allan Ramsay, the builder of the house, give a 98-year lease to Charles and Augustus Brune for £1500 upfront and £1 per annum, with right of access to both Stanley Garden South and Ladbroke Square, with a charge of £2.2s for each garden. 1860: the Brunes having used the leasehold as security for a loan and the bank having foreclosed, the property is sold by auction for £1010 to Richard Michell. 1892: Richard Michell of 3 Kensington Park Gardens sells the lease to R.A. Arnold of 45 Kensington Park Gardens for £900. 1894: Arnold gives a 21-year lease of No. 44 to Lazarus S. M. Pyke for £110 per annum. 1915: Amelia Arnold, presumably the widow of Robert Arnold, dies leaving the leasehold property to Mabel Arnold, spinster. 1918: Mabel Arnold assigns the remainder of the lease to the British Army general and military historian Major-General Sir Frederick Barton Maurice KCB, of 20 Kensington Park Gardens, for £410. |

Listings and other designations (Nos. 24-47) All of the Thomas Allom buildings, Nos. 25 – 47, are Grade II listed which covers alterations to external facades (front, side, and rear), windows, roofs and rooflines, light wells, boundary walls and railings. Any alterations or additions to these structures requires both planning permission and listed building consent. No. 24 is listed separately. The description is as follows:

The description for Nos. 25-47 is:

Oddly, the arch is not mentioned. It presumably counts as part of the terrace. It might nevertheless be worth asking English Heritage to clarify this. |

Recommendations to planners and householders (Nos. 24-47) Relatively few major structural changes have altered the articulation of the north terrace. The main ones include the alteration of the 3rd floor façade of No. 28; the side extensions on either side of the garden entrance at Nos. 33 and 34; and roof extensions at Nos. 34, 40, 41. The addition of an extra storey to Nos. 42-45 could have happened at or near the time of the original build. These alterations, all of which happened some time ago, are structurally permanent. However, there are a number of architectural and/or decorative elements which have been removed or added, and which we hope will one day be restored, perhaps when major renovation projects are being considered:-

Remains of bottle balustrade along the rear roof of No. 29 (2014).

No. 46: missing first floor balcony and balcony railing |

Some Distinguished residents of Kensington Park Gardens

In the 19th century the residents were mostly wealthy merchants, professionals and retired officers, with a good sprinkling of people “living on own means”. Distinguished residents then and since have included the following.

The Labour, Social Democrat and Liberal Democrat politician Roy Jenkins (Baron Jenkins of Hillhead) (1920-2003) and his wife Dame Jennifer Jenkins moved into a flat in No. 2 in 1977, after having previously lived in Ladbroke Square. It was sold shortly before his death.

As stated above, an English Heritage Blue Plaque on No. 7 recognises the scientist Sir William Crookes, who lived here from 1880 to 1919 and was one of the pioneers of domestic electric lighting. Coming of electric light

Again as stated above, No. 9 was the home of Sir John Evans (1823-1908), a distinguished Victorian archaeologist, father of Sir Arthur Evans, the excavator of Knossos, and Joan Evans, the art historian and first woman to serve as President of the Society of Antiquaries as well as the Royal Archaeological Institute.

No. 17 was the former home of intelligence officer, adventurer and ornithologist, Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen (1868-1967).

No. 31 Kensington Park Gardens was the home of Arthur and Sylvia Llewelyn Davies and their five sons, most remembered for their connection to J.M. Barrie and as the inspiration for the Darling family in Barrie’s famous tale, Peter Pan. Sylvia Llewelyn Davies was the daughter of George du Maurier and aunt of author Daphne du Maurier.

No. 37 and No. 14 were successively the home of William Davison, 1st Lord Broughshane (1872-1953), who was Mayor of Kensington from 1913 to 1919, and then M.P. for Kensington for 45 years from 1919 to 1945. He moved from No. 37 to No. 14 in the 1920s.

From about 1919 until about 1840, No. 44 was the home of Major-General Sir Frederick Maurice (1871-1951). He was a somewhat controversial figure as, in 1918 when he was Director of Military Operations on the Imperial General Staff, he wrote a letter to The Times accusing Lloyd George of deceiving the public about the strength of British forces on the Western front. He was forced to retire from the army, but later forged a successful career as a military historian. He was also one of the founders of the British Legion.

His daughter Joan Robinson (1903-1983), who became a highly distinguished Cambridge economist, also lived intermittently at the house with her father and English Heritage is proposing to install a blue plaque to mark her residence there.

This page was last updated 5.5.2024