Keeping the Ladbroke area special

Holland Park Avenue c.1900, looking west. Old postcard, reproduced courtesy of RBKC.

Holland Park Avenue

Holland Park Avenue is one of London’s most ancient thoroughfares. The Romans made it their main road into London from Silchester and the West, but it probably existed as an ancient British trackway long before that. In Roman times it ran through a densely forested area, part of the huge forest that was later known as the Forest of Middlesex (which according to a 12thcentury description was full of red and fallow deer, boars and wild bulls).

After the Romans left, the road appears to have deteriorated to such an extent that the then smaller parallel road to the south that is now High Street Kensington took over as the main way into London for travellers from the West of England. But the old road continued to be used by travellers from Oxford and Uxbridge, and until the 19th century it was known as the Uxbridge Road, or sometimes simply the “North Highway”.

From the Middle Ages onwards, the forest was gradually cleared, to be replaced by arable farmland and meadows. Gravel pits began to be worked at what is now Notting Hill Gate, and a straggling village developed along that part of the road at a fairly early stage. But the Holland Park Avenue section of the road remained in open country until the early 1800s. The grounds of Holland House ran right down to the road on the south side. Almost the only buildings were a large house just west of Princedale Road which was the “ handsome pleasant seat” of the owner of the Norland estate; a farm on the site of the Mitre pub, called Notting Hill Farm; and a hostelry called the Plough (a name appropriately indicative of the rural nature of the area) more or less opposite the end of Campden Hill Road (which was then known as Plough Lane).

The road was known for its robbers and footpads. In the 14th century, one Thomas de Holland was robbed of a cart and its goods at “Knottynghull”, and there are a number of other accounts of robberies down to the 18th century. For instance, in 1751, at the level of Holland Park, two gentleman were robbed of their watches and money by men in black masks – 18th century hoodies – “who swore a lot and appeared to be in liquor”. In 1767, it was decided to install lights and appoint watchmen along the Bayswater Road because it was “infested in the Nighte-time with Robbers and other wicked and ill-disposed persons, and Robberies, Outrages and Violences are committed thereon”, but that no doubt that merely caused the robbers to move west to prey on travellers on the unlighted and unwatched section near Holland Park.

The road was often in poor condition, and this was what led to the establishment of the turnpike gate that became known as Notting Hill Gate, so that tolls could be raised from travellers to keep the road in repair. The private Act of Parliament passed in 1714 to authorise the collection of tolls on the road between Uxbridge and Tyburn (Marble Arch) noted that the road “by reason of the many heavy carriages frequently passing, has become very ruinous and many parts are so bad that the same are very dangerous to such persons as have occasion to travel through the road and in the winter season the road is almost impassable for horses, coaches, chariots, carts and other carriages”. Notting Hill Gate was one of several turnpikes subsequently set up on the road from Uxbridge; it was finally removed in the 1860s.

Around the mid-18th century, 170 acres of land to the north of Holland Park Avenue, between Portland Road and Ladbroke Terrace, were acquired by Richard Ladbroke, a member of a rich family of bankers (the land on the south side of Holland Park Avenue belonged to Lord Holland of Holland House). Richard Ladbroke and his descendants did nothing with the land – beyond enjoying its revenues – until 1819, when the estate was inherited by his grandson, James Weller Ladbroke. The latter determined on developing part of the estate to meet the increasing demand for housing within easy reach of London.

It was natural that he should begin with the frontage of the Uxbridge Road, the only real road in the neighbourhood. In 1823 he signed two agreements with developers, one covering the part of the northern side of the road to the west of Notting Hill Farm, and one the part of the road to the east. Under these agreements, the developers undertook to build a certain number of houses. In exchange, once the houses were built, Weller Ladbroke granted the developers 99-year leases of the new houses, which they could then sub-let for income, paying James Weller Ladbroke a rising ground rent, so that both parties were in profit.

In 1824, the first houses were erected on the north side between Ladbroke Terrace and Ladbroke Grove, and in the next 10 years building extended to Lansdowne Road, the farm being replaced by an inn. Almost all these houses are still standing. The two trios of houses at Nos. 2-6 and 24-28 with their huge and magnificent Doric columns are particularly remarkable, and Nos. 24-26 were deliberately sited to close the vista for those looking down the eastern side of Campden Hill Square, on which building began around the same time.

2, 4, and 6 Holland Park Avenue. Photo 2008.

24, 26 and 28 Holland Park Avenue, which close the vista down the eastern side of Campden Hill Square. ©Thomas Erskine 2007.

In the mid 1830s the building boom collapsed as it became clear that the area was still too far west of London to be attractive. All activity on the Ladbroke estate stopped and the houses on the Uxbridge Road, along with a few built at the same time on the other side of the road and at the southern end of Ladbroke Grove and Ladbroke Terrace, remained for the next decade surrounded by countryside. But in the 1840s, demand for housing revived, and over the next three decades the rest of the Ladbroke estate was completed. The few gaps that remained in Holland Park Avenue were filled in; Nos. 54 and 56, for instance, were built around 1860. Finally, in 1900, Boyne House made way for the Holland Park Station on the new “Central London Railway.”

As was typical of the period, each separate terrace of houses was given its own name and numbering system. Thus, the houses between Ladbroke Terrace and Ladbroke Grove and the first 12 houses west of the Mitre were part of “Notting Hill Terrace” (and Campden Hill Square, which was built by the same developer around the same time, was called Notting Hill Square); then came Boyne Terrace and Boyne House where the Underground Station now is; and finally between the station and Clarendon Road there was Grove Terrace. It was not until 1895 that this part of the Uxbridge Road was renamed Holland Park Avenue and the present street numbering system introduced.

Old and new numbering systems:

1-19 (consecutive) Notting Hill Terrace became 2-38 (evens) Holland Park Avenue.

21-32 (consecutive) Notting Hill Terrace became 42-64 (evens) Holland Park Avenue.

4-8 (consecutive) Boyne Terrace became 66-74 (evens) Holland Park Avenue.

Boyne House and Boyne Lodge (on the site of Holland Park Underground station) became 76 and 78 Holland Park Avenue.

1-10 (consecutive) Grove Terrace became 80-98 (evens) Holland Park Avenue.

Most of the above is reproduced from an article in the Ladbroke Association newsletter, Spring 2008.

Architecture and history of the houses

Holland Park Avenue is a busy main road, but the pavements are wide and the houses set back behind relatively substantial front gardens, significantly mitigating the effects of the traffic. There are no lengthy terraces, but mostly only short runs of two or three houses, sometimes with a gap between the blocks and sometimes not. Although the blocks of houses vary in design, the general pattern is for them to have three storeys plus a basement and full stucco. Between Lansdowne Road and Clarendon Road, shops were long ago built over the front gardens and no sign of the lower façades remain.

Nos. 2-38 evens (between Ladbroke Terrace and Ladbroke Grove)

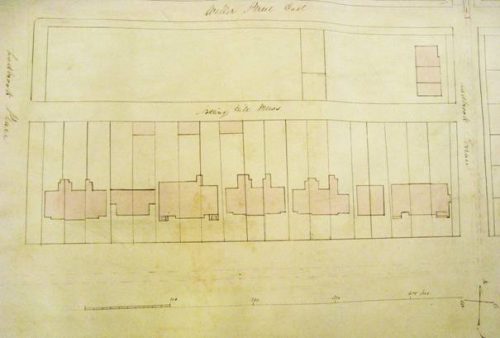

1836 plan of the houses in Holland Park Avenue between what are now Ladbroke Grove and Ladbroke Terrace. Almost all the houses are still there.

These houses all date from the 1820s and are the earliest on the estate. James Weller Ladbroke signed an agreement in 1823 with the developer Joshua Flesher Hanson, the builder of Regency Square, who at about this time was also beginning to build Campden Hill Square on the opposite side. Hanson convenanted to build twenty houses “according to such ranges and levels” as Ladbroke’s surveyor should approve. The arrangement was that, once they were built, Ladbroke would give Hanson 99-year leases of the houses for a ground rent, and Hanson would recoup his outlay by letting the houses – a pattern that became the norm for the development of the Ladbroke estate. By the end of the following year, Hanson had arranged for the erection of Nos. 8-22. But he leased the remainder to Robert Cantwell, who covenanted to build the rest. Cantwell is variously described as an architect, surveyor and builder (the lines between these professions were somewhat blurred in those days) and did a lot of work for the Ladbroke family. He was the designer of Royal Crescent on the adjacent Norland estate and was greatly influenced by Nash’s work at Regent’s Park.

Nos. 2-6 (evens) Holland Park Avenue form a trio with giant Doric columns and a large pediments on the central house (see photographs above). The trio is one of three almost identical ones – the others being at Nos. 24-28 (evens) and Nos. 23-27 (odds) – the latter on the south side of the Avenue and now unfortunately marred by the addition of an extra floor to one of the houses. They were built in the mid-1820s and were almost certainly designed by Robert Cantwell, variously described as an architect, surveyor and builder (the lines between these professions were somewhat blurred in those days). Cantwell did a lot of work for the Ladbroke family and was the designer of Royal Crescent on the adjacent Norland estate. The influence on him of Nash’s work at Regent’s Park is clear. The three houses were given a Grade II listing in 1974. The English Heritage description is:

Early C19. Symmetrical terrace of houses. Stucco 2 storey + attic, and basement, 2, 3, 2 windows. Four engaged giant order Roman Doric columns in antis in front of central house which has flat pediment above attic storey. Some alterations. (cf Nos 24, 26, 28 and 23-27 odd).

There is a 1930s planning application in the London Metropolitan Archives (ref: GLC/AR/BR/17/069872) for No. 2 – then owned by the Consul of Cuba – to have a garage built in its garden, the building that is now No. 19 Ladbroke Terrace. The application contains some interesting plans. No. 4 was converted into flats in 1964 and now consists of a maisonette at ground and lower ground level and two flats above.

Nos. 8-10 (evens) Holland Park Avenue originally consisted of two smallish semi-detached houses built around the same time (see plan above). A history commissioned by the present owners says that No. 10 was built by the architect Robert Cantwell in 1828, which sounds entirely likely, although it is not clear what the source for this information is. Both these houses appear to have been substantially rebuilt or made over sometime around the last two decades of the 19th century (possibly following a fire), resulting in the present two idiosyncratic red-brick houses, quite different from anything in the rest of the terrace. No. 8 is quite definitely a complete rebuild, occupying a larger footprint than the previous house and possibly intended from the beginning as flats. No. 10 could be a remodelling of the existing building; and the porch could be the “open porch of incombustible material” for which permission was sought from the Metropolitan Board of Works in 1857 (deed No. 2321 in RBKC central Library).

In 1971, No. 10 was purchased by the Society of the Church of the Holy Child Jesus (a Roman Catholic community that was founded in England in 1846) to house their nuns and novices.. In 2016 the nuns left, the house was sold and, after various alterations, reverted to being a private residence. Unfortunately, these alterations included the removal of what was probably its original wrought iron railing along the top of its front lightwell. However,it still has its original fire insurance plaque on its façade, a rare survival – in the 19th century, before the days of a municipal fire service, insurance companies had their own fire brigades and these plaques served to indicate which insurance company was responsible for each building.

Nos. 8 (on the right) and 10 Holland Park Avenue in 2008

The historical inhabitants of 10 Holland Park Avenue

A historian has traced the occupants of No. 10, and they give a good picture of the sort of people who lived in these houses. The first occupant appears to have been a widow, Laura Fenwick, no doubt living on her investments or on an annuity from her husband. She was there until 1843. The house then passed to a maiden lady, Miss Greigson. Both would no doubt have had two or three servants, and possibly some relatives living with them. By 1851, the householder was Captain Francis Hepburne, a 53-year old Army officer, with his wife and three servants. The following year the house passed to another widow,Georgina Vyvyan. In 1857 it was acquired by a banker, Charles Leboz Stephens, who was there with his wife until at least 1881. After his death in 1894, a Chancery barrister, John Black, moved in. By 1900, according to the Post Office directory, the occupant was William Maurice Anderson, a young Army doctor who later became Chief Army Medical Officer for the North-West Frontier Province in British India. By 1902, however, the records show a Mrs W. McNeil Whistler as the occupant. She must have been related by marriage to the American artist James McNeil Whistler, but it is not clear how. In 1910 the house passed to A.D. Ralli, a partner in the firm of Ralli Bros, East India merchants. He sold the house in 1919 to Frank Pollard Wilson, a company director. His widow was still there in 1940, when she left London to be out of the way of the bombs. She never returned, and after World War II the house was taken over as an Officers’ Club and training centre for the Girls’ training Corps. In the late 1950s it was acquired by a Mrs B.M. Wycherley who ran it as a boarding house until it was acquired by the Society of the Holy Child Jesus. |

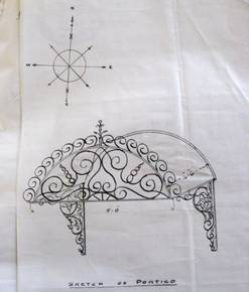

Nos. 12-16 (evens) Holland Park Avenue form another semi-detached trio of stuccoed houses, in a simpler style, but again built around the same time with three floors plus basement. No. 14 acquired a rather beautiful wrought iron porch in 1898, a period when it was fashionable to add porches and porticoes. Otherwise, the fronts of these houses are probably little changed from when they were built. Nos. 12 and 16 have retained what are probably their original wrought iron railings along the top of their front lightwells and No. 14 has what is probably a later replacement following the same pattern.

No. 12 was for 50 years until 2013 the home of the Labour politician Tony Benn (1925-2014) and his family. A plaque on the house commemorates his wife Caroline deCamp Benn, an educationalist and a leading light in the development of the Holland Park Comprehensive School (which the Benn children attended).

No. 16 was from 1907 the home of the German professional strongman and showman Eugen Sandow (1867-1925) from 1907 until his death. He popularised bodybuilding and organised what is said to be the first bodybuilding competition in 1901 in the Royal Albert Hall.

Nos. 12-16 (evens). Tony Benn’s old house is on the right. ©Thomas Erskine 2006

Sketch of the portico of No. 14 from the 1898 planning application in the Kensington and Chelsea Local Studies collection.

The plan above indicates that the next three houses, Nos. 18-22 (evens) Holland Park Avenue, also originally formed a symmetrical three-house block, probably very similar to Nos. 12-16. No. 18 retains the most original features. Nos. 20 and 22 appear to have lost their original top floors, now replaced by dormers. The Polish-born artist and illustrator Jan Le Witt (1907-1991), who moved to London in the late 1930s, had his studio at No. 22. There is a set of deeds in the Kensington Local Studies centre tracing the 19th century ownership of No. 20, from when James Weller Ladbroke granted a 96½-year lease in 1826 to a Miss Catherine Vyvyan, by arrangement with Joshua Flesher Hanson, another of the developers working with James Weller Ladbroke (he also developed Campden Hill Square), to whom Ladbroke had originally given a 99-year lease. In the mid-1880s the house was briefly the home of Matthew White Ridley (1837-1888), a painter and etcher who founded an art school in Notting Hill.

Nos. 24-28 (evens) Holland Park Avenue are the next of the handsome Cantwell trios with massive central columns, matching that at Nos. 2-8. The block is deliberately sited to close the vista down the east side of Campden Hill Square. They too were given a Grade II listing, in 1984. The English Heritage description reads:

Symmetrical terrace of houses. Early C19. Stucco. Two storeys, attic and basement. 2:3:2 windows. Four engaged giant order Roman Doric columns in antis to central house with flat pediment above attic storey. Cast iron to first floor balconies. Unaltered. (cf 2, 4 and 6).

Nos. 30-32 Holland Park Avenue form a group of two semi-detached houses with doors at the side and good Victorian ironwork. Apart from the ironwork they are relatively untouched and were given a Grade II listing in 1969. The English Heritage description is as follows:

Early C19. Stucco pair, 3 storey + basement. Two windows + 1 window over door at side. Good hooded Iron balconies across front at ground floor, and first floor window guards. Slate roof to eaves. A group.

30-32 Holland Park Avenue. ©Thomas Erskine 2006

No. 30 was the home of Alasdair Milne (1930-2013), Director-General of the BBC 1982-1987.

The final group of houses in this stretch are the threesome Nos. 34-38 (evens) Holland Park Avenue. The first two seem to have been built separately from No. 38, as James Weller Ladbroke gave leases of Nos. 34 and 36 in 1826 to an Upminster builder called William Hammond, who had presumably been responsible for building the houses, whereas the lease of No. 38 was given to Robert Cantwell. Nos. 34 and 36 have only two storeys plus basement and handsome Victorian hooded iron balconies. No 38 has Punjani’s newsagent underneath it and may have been designed from the beginning to have a shop incorporated in it. There is a plan in the Local Studies Library that shows that there was certainly a shop in the present position by 1861(deed 2357).

LISTINGS AND OTHER DESIGNATIONS

Recommendations for new designations The following are the preliminary views of the Ladbroke Association. We would be grateful for any comments.

|

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PLANNERS AND HOUSEHOLDERS These are provisional recommendations on which we would welcome comment.

|

Nos. 40-78 evens (between Ladbroke Grove and Clarendon Road

There was originally a farm on the western corner of Holland Park Avenue (or the Uxbridge Road as it was then) and Ladbroke Grove. When James Weller Ladbroke began to develop the part of Holland Park Avenue west of Ladbroke Grove Road, he at first left the one-and-a-half acre plot with the farm untouched. He signed an agreement in 1823 with a brick and tile maker called Ralph Adams for the development of the land west of the farm. Ralph Adams built Nos. 54-74 over the next eight years. Nos. 42-52 were developed slightly later on land within the curtilage of the farm, in the early 1830s, and the Mitre sometime after that.

The Mitre public house at No. 40 Holland Park Avenue is on the site of the original Notting Hill Farm. It seems from deeds in the possession of the owners that the original pub was erected at least by 1844, and possibly earlier. The present building is a replacement built between the world wars, nicely decorated with mitres on the roof parapet. It is not clear why it was called the Mitre; there are no obvious episcopal connections. In the 1980s, following the highly successful 1984 television series based on Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet, the pub was renamed by a new owner The Raj, and under yet another owner it became the Rat and Parrot, part of a chain of similarly named pubs. But neither incarnation was particularly successful, and the next owners returned the pub to its original name.

The Mitre in 2006

The pub was originally set back a bit on the Ladbroke Grove side and in the 1850s had stables and a coach house round the corner in Ladbroke Grove. An 1890 planning application (LCC case No. 482) in the Local Studies section of Kensington Public Library shows that there was a glass conservatory on the corner. The application was for a rather fancy new conservatory, but it was refused.

John Weller Ladbroke granted leases of Nos. 42-52 Holland Park Avenue to John Drew of Pimlico, builder, in 1833, indicating that they were completed around then. Drew had put up a range of attractive stucco and half stucco houses. The first two, Nos. 42 and 44, are unusual in being low-built with three bays, providing exceptionally spacious interiors.. Originally they had two storeys plus basement; dormer floors were added in 1989 to the same design for both houses (at the same time some ugly 1960s windows that had been inserted into both front and rear facades of No. 44 were replaced by ones matching the originals). Both houses are alone in this block to retain what are probably their original wrought iron railings along the top of their front lightwells.

These houses were listed Grade II in 1984. The somewhat terse English Heritage description is:

Pair of houses. Early 19th century. Two storeys. 3 windows each. Yellow brick. Channelled stucco to ground floor. Stucco blocking course. Iron window guards to fist floor. Iron verandah to ground floor of No. 44.

Nos. 46-52 (evens) form a uniform terrace of stucco houses with three storeys plus basement. They too were given a Grade II listing in 1984. The description is:

Terrace of houses. 19th century. Three storeys and basement. Three windows each. Stucco. Channelled ground floor. Iron window guards to first floor. No 50 has iron hood to door. Cornice to Nos 46, 48 and 50 mutilated.

The wrought iron “hood” on No. 50 was probably added around the 1880s, when there was a fashion for these things. The cornices have been partially re-instated since the listing.

The listed three-storey terrace at Nos. 46-52 Holland Park Avenue in 2008

The backs are plain stock brick. Regrettably, No. 52 has acquired a disproportionate full-height back extension. No. 50 has a much smaller two-storey one. The others have small one storey closet extensions at the rear.

Leases of Nos. 54-74 were granted by Ladbroke to Ralph Adams of Gray’s Inn Road, brick and tile maker, in 1826–31, indicating that the houses were completed at around those dates. Adams had built a series of villas in groups of two or three.

Nos. 54, 56 and 58 form a full stucco three villa group, separated from the Drew terrace by a slim gap (now infilled by a second front door with floor above). Nos. 54 and 56 are Victorian in style and listed Grade II. The English Heritage description is:

Houses. Circa 1860. Three storeys plus basement. Each of 2 bays wide. Stuccoed. To left of each a 3 storey canted bay rising from basement to first floor with elaborate 2 storey iron verandah and balustraded parapet. Doors with pilasters and cornice. Crowning cornice and blocking course (trimmed to No 56).

54 (on the right) and 56 Holland Park Avenue. ©Thomas Erskine 2006

Although the description suggests that these two houses date from around 1860, the 1863 Ordnance Survey map shows Nos. 54-58 as a triplex flat-fronted group with no bow windows, presumably the original form. Moreover, some of the fenestration of No. 54 in particular looks more 1830s than 1860s – the window immediately above the door of No. 54, for instance, matches pretty exactly that above the door of No. 58. So it seems more likely that all three date from around 1830 and originally looked like No. 58, but some time in the 1860s or thereafter Nos. 54 and 56 acquired an extra floor and were “Victorianised” by the addition of a full-height semi-circular extension (this was a period when bow windows became popular), together with pilastered decoration round the doors. No. 56 has a similar semi-circular extension behind, rising to two floors. It is unfortunate that, in 1985, despite the objections of the Ladbroke Association at the time, No. 54 was granted permission for a mansard extension on top of its extra floor. This, and the different height of the roof parapets, spoil the symmetry of this otherwise attractive pair. The back of No. 54 has been completely rebuilt at some time and has been rendered. No. 56 retains its brickwork at the back but it has been painted over.

Only No. 58 still has what looks like most of it its original rear elevation, with mellow brickwork, although the roof has been remodelled to allow a dormer floor. On its front elevation this house is full stucco and would originally have had no dormer floor. This house was the long time home of the detective novelist P.D.James (1920-2014).

Nos. 58 and 60 Holland Park Avenue, sole relatively untouched survivors of two triplex groups of villas. ©Thomas Erskine 2006

No. 60 is all that remains of yet another detached full stucco trio of houses dating from the early 1830s, although some of the detail looks to have been added later. Beyond that there was originally a pair of semi-detached half stucco villas, of which only No. 68 remains. The original houses between No. 60 and No. 68 have sadly disappeared completely (they were bomb-damaged in the Second World War) and were replaced in the 1960s by Kent House (Nos. 62-66), a mundane brick-built block of flats. The original No. 62 (No. 31 Notting Hill Terrace) was in the 1850s and early 1860s the home of the Punch caricaturist John Leech (1817-1864).

Nos. 70-74 are shown on the 1863 map as another triplex of villas, and were probably similar in design to the others on this block, probably with full stucco. It is not clear why they were replaced by the present building, which is definitely late Victorian in style (it was probably built in the 1880s as it is already shown on the 1893 Ordnance Survey map). It retains some of the shape of the original triplex with the central house slightly set forward. No. 74 has been given a touch of class with its typical late Victorian glass and wrought iron canopy over the door.

Nos. 72-74 evens Holland Park Avenue. ©Thomas Erskine 2006

Listings and Article 4 Directions Nos. 42-52 and Nos. 54-56 evens are grade II listed. Nos. 58, 60 and 68-74 are subject to an Article 4 Direction removing permitted development rights in respect of Nos. 58, 60 and 68-74 evens in respect of alterations of front windows or doors. Nos. 70-72 have a Category I roofline in the Conservation Area Proposals Statement, the strongest recommendation for protection. |

Recommendations to householders and planners These are provisional recommendations on which we would welcome comment. Paint colour:

Railings facing the street: these houses probably had full length iron railings on their street boundary, no doubt removed during World War II. Now there is a mixture of styles, mostly involving dwarf walls surmounted by railings. We hope that these walls can be kept as low as possible and traditional railings used. The solid metal panels behind the railings on No. 54, for instance, strike a rather jarring alien note. Similarly, at Nos. 70-74 where high walls have been installed not only on the street boundary but also between the front gardens, this is out of character and does mar the otherwise open and greenery-filled look of the street. We recommend strongly against the building of any further walls or opaque structures and hope that those tha\t exist will one day be removed. Lightwells: some of the front lightwells have been enlarged by partially digging out the garden. We recommend against any further digging out of the front gardens of the listed houses as it would affect their original character. Digging out in front of the other houses should not extend beyond one third of the garden, as part of the character of this stretch is the leafy front gardens. Gaps: there is an important gap between Nos. 58 and 60 that should not be infilled. There is already partial infilling of the other remaining gap in this terrace between Nos. 52 and 54, but set back above ground floor level so the original gap can easily be deduced. Any further infilling of this gap or that between No. 68 and No. 70 should be resisted. Dormers: we would normally oppose any further dormer floors on this interesting early terrace. But since a dormer has been built on No. 54, there could be a case for a matching one of the same style and dimensions on No. 56, as these are a pair and the present effect is one of imbalance. Rear extensions: we hope that only modest single floor back extensions or conservatories will be allowed on this terrace. Rear brickwork: the rears of these houses were built to be plain brick, and it affects their character, as well as the rear view as seen from neighbouring houses, if the brick is painted over. |

Holland Park Station and Nos. 80-98 evens (between Lansdowne Road and Clarendon Road)

Photo ©Thomas Erskine 2006

Ladbroke’s 1823 agreement with the builder Ralph Adams covered this stretch too. The leases granted to Adams indicate that he completed the houses that he was contracted to build around 1831, although other documents suggest that the houses at the western end may not have been completed until 1845. Where the Underground now stands, Adams built a pair of large semi-detached villas well set back from the road and with grounds extending to Lansdowne Mews. The first of these was called Boyne Terrace House and the second Boyne Terrace Lodge. Next to them he built a terrace of eight narrow houses (Nos. 1-8 Grove Terrace, now Nos. 82-94 Holland Park Avenue) plus a larger one on the corner with Clarendon Road (subsequently divided into two houses, Nos. 9-10 Grove Terrace or Nos. 96-98 Holland Park Avenue). All of these buildings have been demolished or altered beyond recognition by the construction of shops in what were their front gardens.

Boyne House and Boyne Lodge (Nos. 76 and 78 Holland Park Avenue after the street was renamed and renumbered in 1895) were demolished in around 1900 to make way for the Underground (see separate entry). These numbers are now given to the two low rise infill buildings between the Underground station and the beginning of the terrace proper.

Nos. 80-90 were a stucco-fronted three storey terrace not dissimilar (judging by old photographs) to that which Adams had built at Nos. 46-72 Holland Park Avenue. They were originally set back from the road – the instructions to Adams was to build them at least 20 feet from the highway. But single storey shops were built in front of them so that their gardens have disappeared completely. The 1863 Ordnance Survey map indicates that all the shops along the stretch between Lansdowne Road and Clarendon Road were already there by then. The 1871 census records among the residents a provider of homeopathic medicine; a wine-merchant; a watchmaker; a draper; a linen draper; a baker; a butcher and a grocer

In 1987, planning permission was sought and granted for the demolition and rebuilding of Nos. 84-90, which were then pretty dilapidated. English Heritage, commenting on the application, noted that Nos. 88 and 90 were still very much in their original state and expressed the view that their demolition would be “most regrettable”. The Council nevertheless granted permission for the redevelopment, which involved the entire block back to Lansdowne Mews. The front façade was rebuilt in the style of the old one, albeit with dormer floors, and a sort of terrace with bottle balustrade has been created on top of the shops, a pastiche rather out of character with the area. Now No. 82 gives the best idea of what this terrace looked like – although the shops mean that we have no idea what the ground floors were like. The writer Ford Madox Ford (1873-1939) lived at No. 84 between 1907-1910, above a poulterer and fishmonger, during which time he founded the English Review (1908-1937), which published works by many of the leading writers of the day.

Nos. 92-94 are in a quite different 1840s style, taller with stock brick façades, full height stucco pilasters and windows at first floor with heavy cornices (lost on No. 94). Unfortunately the brickwork has been painted over on No. 94, but this must have been an extremely handsome pair (see old postcard below, probably dating from the early 1900s). The double corner house (Nos. 96-98) then returns to the pattern of the earlier part of this terrace, with a simpler stucco pattern although retaining the extra height.

|

Listings and Article 4 Directions None of the buildings is listed, although we believe that the Underground station is worthy of a Grade II listing. Nos. 80-82 and 92-98 have Article 4 Directions requiring planning permission for alterations of front doors or windows. |

|

Recommendations to householders and planners These are provisional recommendations on which we would welcome comment. We very much hope that the missing detailiing on the facade of No. 94 will one day be restored and the paint removed from the brickwork, so that the paired villas at Nos. 92-94are restored to their glory, at least at the upper levels. The restoration of a traditional upper window on No. 92 would also be an improvement. |

Last updated 5.7.2023