Keeping the Ladbroke area special

Panorama: south-western end of Blenheim Crescent. © Thomas Erskine 2006

Blenheim Crescent

Blenheim Crescent runs from Portobello Road west across Ladbroke Grove and then curls round to the south to join Clarendon Road. The section between Portobello Road and Kensington Park Road consists of shops and cafés, including at one time the Travel Bookshop that inspired the 1999 film Notting Hill; the rest of the street is residential. The odd numbers are on the south side and the evens on the north. From Ladbroke Grove west, the whole crescent is now lined with magnificent mature cherry trees.

Until the middle of the 19th century, what is now Blenheim Crescent was open country. Plans began to be developed for creating a road in the 1840s. In preparation sewers were laid at any rate at the Clarendon Road end in about 1850, and some building leases were let (see box below). But the demand for housing had collapsed and the lessees probably failed to raise the necessary finance. At any rate, nothing much further happened until the 1860s, when the last great wave of development on the Ladbroke Estate began.

By 1860, the Ladbroke family had sold the land on which Blenheim Crescent now stands. Most of it had passed into the ownership of Charles Henry Blake, a retired Calcutta merchant who had turned to property speculation. In partnership with Charles Chambers, variously described as a timber merchant or an engineer, he was mainly responsible for developing the road. It was a propitious moment. There had been a revival in the demand for houses and the area was made a lot more desirable by the opening in 1864 of an extension to the City and Hammersmith Railway with a station in Ladbroke Grove (then called Notting Hill Station).

An Ordnance survey map dating from 1863 indicates that the street had been fully laid out by then and that a cluster of houses had gone up at the Clarendon Road end. In particular, a terrace of 27 houses had been erected at the end of the south side. This row of houses (now Nos. 83-135) was baptised “Blenheim Crescent”, and subsequently gave its name to the whole street (the street was originally called Sussex Road west of Ladbroke Grove and St Columb Road east of Ladbroke Grove). The only structures in the rest of the street were the present No. 51 near the south-east corner with Ladbroke Grove; the high back garden wall of a convent on the north-east corner with Ladbroke Grove; and a lone public house, the Arundel Arms, on the corner of Kensington Park Road at what is now No. 14 Blenheim Crescent (this pub was subsequently renamed the Blenheim Arms and went out of business only in the early 2000s).

Construction obviously proceeded apace, as by the time of the 1871 census, almost all the present houses had been completed and the street had acquired its present name. 14 houses were still empty, but the vast majority had found tenants. It seems likely, therefore, that Blake did well out of Blenheim Crescent (he was one of the few developers of the Ladbroke estate not to come to financial grief).

Unlike some streets on the Ladbroke estate, where whole streets or sides of streets were constructed by the same person, Blenheim Crescent is a patchwork of different styles. The building plots were let on 99-year leases to different builders, often in quite small packages, and each did his own thing. Once the houses had been constructed, the builders would let them and cover their investment from the rental income; a (usually rising) ground rent remained payable to the landowner.

A typical developer’s lease A copy of John Weller Ladbroke’s original lease to a developer for the land at the northwest end of Blenheim Crescent (between what are now Blenheim Crescent and Clarendon Road) survives in the Kensington and Chelsea Local Studies Library. It dates from 1846 and the intended developer was Richard Roy. The four acres of land, described as “part of two fields heretofore called 15 Acres and 18 Acres”, were leased to Roy for 94 years at a peppercorn rent. He was required to complete the new roads that had been laid out by Ladbroke’s surveyor, constructing pavements etc. There were then detailed provisions covering the building of any houses on the plot. There could be no more than twenty. Each had to be worth at least £500; and at least half had to be worth £1,000. Brick or stone walls or iron fences had to separate the gardens. There were no specifications as to the general design of the houses (although everything had to be approved by Ladbroke’s surveyor), but numerous specifications on the construction (e.g. all party walls had to be at least 18 inches thick) and on the materials to be used. The oak timber, for instance, had to be “growth of this country and all other timber to be from the Baltic, either Memel, Dantzig, Riga or Gothenburg”. Finally, there was a clause which seems to have been fairly standard in Ladbroke’s leases, forbidding the developer to exercise or allow to be exercised on the land the trades of “soap boiler, tallow melter, tripe dresser or boiler, catgut spinner, hog skinner, boiler of horseflesh, slaughterman or any other noisome or offensive trade” that might inconvenience the neighbours. |

What sort of people lived in Blenheim Crescent?

The whole of the Ladbroke estate was very much a middle class area in the 19th century, but the inhabitants of Blenheim Crescent were from the beginning quite a lot less grand than those in the southern part of the estate. The Portobello end seems always to have been occupied by tradesmen. Further up the street, the occupants in 1871 were chiefly professionals, although at the lower end of the scale compared to the occupants of the grander houses to the south. They included accountants, clerks, civil servants and merchants. Many of the houses were occupied by widows living on a (probably small) income from dividends or annuities, usually with a couple of children or other relatives living with them. Almost all the households included one or two servants. Several of the houses were lodging houses.

There was also a significant artistic element in the street. Apart from the artists at the purpose-built house at No. 43-45, Hablot Knight Browne (1815-1882), the pseudonymous Phiz who was the main illustrator of Charles Dickens’s novels, had taken No. 19 where he was living in 1871 with his wife, seven of his nine surviving children, a cook and a housemaid. He does not seem to have remained there long, as according to Barbara Denny’s book Notting Hill and Holland Park Past, from 1872 to 1880 he was living inLadbroke Grove. There were also artists at Nos. 83 and 87 and at No. 89 an occupant who described himself as a “life student”.

In 1906, the French artist André Derain (1884-1954), one of the principal members of the Fauve group, stayed at No. 65 on a long visit to London. He had been sent over by his dealer and during his visit did a series of 30 paintings of London scenes that echoed Monet’s earlier ones, but in bright contrasting colours typical of the Fauves rather than Monet’s mist and smoke.

Blenheim Crescent seems to have gently declined over the first half of the 20th century, more and more of the houses going into multi-occupation. The history of No. 38 is fairly typical. Its first occupant in 1868 was Charles Barber, late of H.M. Indian Civil Service. The next occupant was a member of the prosperous merchant classes, a 31-year-old tea broker named Thomas White. He was the senior partner in the firm of George White and Co. In 1871 he had living with him his wife, four young children, a cook-domestic and two nursemaids, and he travelled to work every day by private carriage to Eastcheap. By 1881, the house was in the possession of a widow living on income from house property, a traditional and respectable source of revenue for middle-class folk. By 1891, the widow had died and the house had passed to her brother, also a man of independent means. The house then changed ownership a couple of times before becoming the residence of the local doctor in the early 1900s. By 1924, however, the house had been divided between two families, and by 1936 there seem to have been` three families living there. It was not until 1991, when the house was in a very dilapidated state, that it was purchased by a family who did it up and converted it back into a single family residence.

During the Second World War, Blenheim Crescent mainly escaped direct hits on the houses, although several bombs fell in the street during the Blitz in 1940, causing considerable damage at the north-west end, and elsewhere in the street damaging gas mains and no doubt blasting the windows of neighbouring houses. The force of the blast from a land mine in St Mark’s Road was so strong that the bay windows at the back of numbers 89 and 91 Blenheim Crescent collapsed.

By the 1950s, Blenheim Crescent was very scruffy and down-at-heel, on the edge of the notorious Rachman area. In 1958, the Notting Hill race riots spilled over into Blenheim Crescent. The Times recorded how on the night of 1-2 September petrol bombs and milk bottles were thrown from rooftops as the rioting crowds surged into Blenheim Crescent.

One of the residents of the Crescent (at No. 115) was a Presbyterian Minister, the Rev. Bruce Kenrick (1920-2007), was so horrified by the bad housing and social deprivation that he saw around him in Notting Hill that he founded first the Notting Hill Housing Trust in 1963 and later Shelter in St Martin’s in the Field (in 1966). As his Times obituary put it, he saw Rachmanism close up: “I came home from work one summer evening and saw all the belongings of our next-door neighbour piled on the street. While she was out with her child, the landlord had come and removed all her things from the one room, locked the door and dumped them all on the pavement”. When Kenrick founded the Trust, he mortgaged his own home to buy another house, which was renovated and let to poor families. Thus began a programme of buying houses at auction, renovating them and renting them to needy families.

With the 1960s, a slow ascent to prosperity began, with families increasingly taking over the multi-occupied rented accommodation characteristic of the Rachman era. One of the first of the new wave of residents was the fashion designer Ossie Clark, who moved into a flat at No. 51a in 1966. Now the street is more desirable than probably any time in its history. Ironically (and despite a few acts of vandalism like that by the Kensington Housing Trust described above), the Notting Hill Housing Trust, by buying up then despised and crumbling Victorian houses in the streets of North Kensington, may have been responsible for saving some of the houses which are now so valued.

Architecture

Blenheim Crescent at the Portobello Road end (Nos. 1-15)

14 Blenheim Crescent, on the corner of Kensington Park Road, photo looking east towards Portobello Road. No. 14 used to be a pub called first the Arundel Arms and then the Blenheim Arms. (Photograph © Thomas Erskine 2006.)

The section of Blenheim Crescent between Portobello Road and Kensington Park Road (Nos. 1-15 odds and 2-14 evens) seems from the beginning to have been intended for tradesmen, with residential premises above, and on the south side quite a bit of the old shop-front decoration still survives. It probably dates from the early to mid 1860s, as an old deed in the Kensington and Chelsea Library refers to a lease of No 15 dating back to 1864 (this block was, however, still undeveloped at the time of the 1863 Ordnance Survey map). As mentioned above, No. 14 was the first of the buildings erected as a public house called the Arundel Arms (developers were rather inclined to build pubs first, as a way of relieving their workmen of their wages so as to benefit the developers’ own pockets). The other buildings all have shops below and two floors above. They were originally brick with stucco surrounds to the windows at first and second floor. Most have now been stuccoed.

On the south side quite a bit of the old shop-front decoration still survives, including the original decorative corbels at the sides of the fascias. The upper floors were brick with good stucco window dressings, of which several survive.

The buildings on the north side were all stucco at first and second floor level. However, the upper floors of No. 2 (which had been stucco) and the façade of No. 4 (which was structural instable) were both rebuilt in London stock brick in the 1980s, to the detriment of this terrace. All the shops bar the betting shop at No.6 have some sort of stall-riser and thus retain something of their traditional look. The interestingly designed shop window at No. 2 predates the rebuild and may go back to an art deco era.

Old photo of Blenheim Crescent from Portobello Road

At the time of the 1871 census, residents of this section included butchers, a greengrocer; an umbrella-maker and a tobacconist. No. 12, now Mike’s Café, was already a coffee house. Some of these small houses had two or three families living in them, the shop-keepers no doubt letting part of their premises.

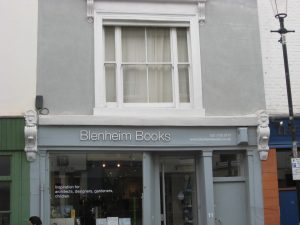

In 1979, Sarah Anderson opened the Travel Bookshop at No 13 (expanding into No 15). This was the inspiration for the shop in the film Notting Hill, although the building did not actually figure in the film. Sadly it closed in 2011 and the premises are now occupied by the Notting Hill Bookshop.

This short stretch of shops includes two well-known shops for foodies: Books for Cooks at No. 4 was founded by Heidi Lascelles in 1983 and now has London’s largest array of books about food and drink; and the tiny but comprehensive Spice Shop at No.1 in the two-story building built many years ago in what was originally a gap between 197 Portobello Road and 3 Blenheim Crescent).

Unfortunately, high rents are increasingly driving out the small shopkeepers. It has not helped that charities such as the Notting Hill Housing Trust (that owns property in Blenheim Crescent) have, in order to fulfil their duty to maximise the profits on their commercial portfolios, had to sell their properties to developers rather than to the incumbent shopkeepers. The Travel Bookshop (opened by Sarah Anderson in 1982), made famous by the film Notting Hill, was one of those that did not survive.

The Travel Bookshop in 2007

Listings and other designations; and recommendations for new designations None of these buildings is listed, nor are they subject to any Article 4 Directions. They still retain much of their original character, however, and we recommend that Article 4 Directions should be made so as to require planning permission for alterations to the fronts of the buildings. The former Arundel or Blenheim Arms at No. 14 in particular is a fine building that cries out for protection. |

Recommendations to owners and planners

|

Blenheim Crescent between Kensington Park Road and Ladbroke Grove: south side (Nos. 17-51 odds)

On the south side of this part of Blenheim Crescent, there are three distinct terraces of houses. Nos. 17-31 consist of a row of five-story half-stucco houses that were probably built in the mid or late 1860s. They have fussy window decoration and are not the most elegant in the street. The Greater London Council’s Survey of London describes Blenheim Terrace as being built in a “debased classical style” that demonstrated “the marked deterioration of taste which was beginning to take place”, and maybe it was this range of houses that the writer had in mind. But the row is not without merit; it is built as a symmetrical terrace with the end and middle houses having different fenestration from the intervening ones and the two middle ones having adjacent porches,. Unfortunately, some of the detailing on some of the houses has been lost and one has completely lost its porch. Only Nos. 29 and 31 retain their original rather elegant stucco and ironwork first floor balconies; on the others they have been completely lost or replaced with a variety of mostly inelegant substitutes. The terrace is half stucco with London stock brick; unfortunately the brickwork has been painted over on No. 2.

The houses at Nos. 33-41 are plainer and better proportioned. Rather oddly, however, there is no symmetry to this terrace; the house at the western end is larger, but the eastern end of the terrace joins the terrace containing Nos 17-31 unceremoniously and without a corresponding book-end house. No doubt some financial crisis among the developers of the road caused this disconnect.

The houses in final range on this side, Nos. 43-51 are of considerable interest and individuality. The three houses at Nos. 47-51 were probably among the earliest to be built, as No 51 already appears on the Ordnance Survey map of 1863. They are among the few in the Crescent to have been built with full stucco.

Blenheim Crescent south side, seen from Ladbroke Grove looking east. No. 51 is in the foregound. © Thomas Erskine 2006

The detached house at Nos. 43-45 is very much a one-off. Although it is two houses, it has a single front door and doors between the communicating wall, and contains four purpose-built artist’s studios with huge north-facing windows, as well as flats for accommodation. In 1871 a “painter” called Henry Ivermee was living at No. 43 with his wife (he gives his birthplace as “At sea, near China”). It is still listed as two dwellings in the 1881 and 1891 censuses, but by 1891 No. 43 was occupied by two artists – William Watson, a sculptor; and Thomas Liddall Armitage (1856-1924), then listed also as a sculptor but later known as a genre painter. The two houses seem to have been joined together shortly after that, and it was probably at that stage that the huge north-facing windows were installed. It seems to have been run almost as a commune, with a number of other artists and their families also living there. Among the more recent residents was Joanna Carrington (1931-2003), a distinguished painter of landscapes and interiors who was the niece of the Bloomsbury painter Dora Carrington. The double house has now been turned into six residential flats. Its current name of “Artisan House” seems to be a modern invention.

Artisan House, at 43-45 Blenheim Crescent: a perfect house for painters. © Thomas Erskine 2006

Both Nos. 47 and 49 show similar signs of being artists’ houses, with their big top windows facing north, and No. 47 was also owned by Thomas Liddall Armitage. So it seems that these houses formed quite a little artists’ colony.

The ground floor and basement of No. 51 were one of the several dwellings in the area that were once inhabited by the science fiction writer Michael Moorcock.

Listings and other designations None of the houses is listed. Nos. 41B and 43-51 odds are subject to an Article 4 Direction requiring planning permission for alterations to front windows or doors (1996). Recommendations for new designations Nos. 17-41 are not are not among the most elegant houses on the estate, but they are nevertheless Victorian terraces worth preserving. We recommend that all should be subject to Article 4 Directions in respect of alterations to their front elevations. |

Recommendations to householders and planners

|

Blenheim Crescent between Ladbroke Grove and Kensington Park Road: north side.

The whole north side of this part of Blenheim Crescent is now occupied by a modern housing estate. Originally, a row of 1860s houses (Nos. 16-34; before the renumbering of the street they were Nos. 1-10 Albury Villas) started at Kensington Park Road and ran about half way along the block. It is possible that this was the terrace referred to in Florence Gladstone’s (not always reliable) book Notting Hill in bygone days, where she writes that “in 1867 a charming terrace of small houses was built in Blenheim Crescent originally called Sussex Road; these houses were on the edge of the country and the scent of new-mown hay wafted in at the windows across the garden of the Convent”. The area between this terrace and Ladbroke Grove was fully taken up by the garden of a large convent, the main buildings of which were in Westbourne Park Road. But in the 1970s, when the convent moved out of London, the Council redeveloped the entire block bounded by Blenheim Crescent, Ladbroke Grove, Westbourne Park Road and Kensington Park Road, and all trace of the old buildings has disappeared. This block is outside the conservation area.

Blenheim Crescent west of Ladbroke Grove: south side (numbers 53-137 odds)

The construction of the 41 houses (numbers 53-135) in the terraces on this side between Ladbroke Grove and Clarendon Road was entrusted to no fewer than nine different builders or developers in the early 1860s. The net result is a terrace that is superficially similar in that all the houses have three floors plus a basement, with a raised ground floor, and most are half-stucco with pillared porticoes (all are plain brick behind). But the differences of style between the different builders are clear. Building began from the west and, interestingly, the ranges become progressively taller, better proportioned and generally more handsome from west to east. The older Nos. 117-135 at the western end show distinct signs of corner-cutting, with no pediments and clumsy detailing. The more spacious construction of the later ones may be due to increasing confidence in the housing market as the 1860s progressed. All give onto the Blenheim-Elgin communal garden and have their own generous private gardens separated from the communal garden by railings. None of the ranges in Blenheim Crescent, however, comes near to matching the grandeur of the earlier and larger houses in the southern part of the Ladbroke estate, and some are quite shoddily built.

There is only one entrance to the garden directly from Blenheim Crescent, through a narrow gap between Nos. 81 and 83, still with its original gate and railings (classified in the Conservation Area Proposals Statement as an example of an “important gap”). But householders each have their own private entrance from their back gardens. The communal garden is shared with the corresponding houses on the north side of Elgin Crescent. There is another gate into the communal garden in Ladbroke Grove. A good informal history of the Blenheim and Elgin Crescent Garden has been written by Catherine Thompson McCausland.

The following sub-paragraphs describe the ranges built by each of the individual builders.

- No. 53: a builder called Richard Crowley was given a building lease by Charles Chambers in 1963 and built a double-fronted stuccoed house quite different from anything else in the street. Crowley was also responsible for 91-93 Ladbroke Grove, a pair of not dissimilar stuccoed houses;

- Nos. 55-73 were undertaken by a surveyor called Thomas May, who was also granted his building leases in 1863. He seems to have done the work in two stages as there are two distinct ranges of houses, Nos. 55-61 and Nos. 63-73. Both ranges are half-stucco with pillared porches, but with slightly different fenestration – the upper ground floor bow windows on the second range being smaller. The level of the roofline also changes between the two terraces. Unusually for terraced houses of the period, the higher floors have one single and one double window instead of the more normal two single windows

- Nos. 55-61 have unfortunately had their upper floor brickwork painted over, which means that the window dressings cannot be seen to full advantage. Their rear elevations are plain London stock brick, with bow windows at ground and lower ground floor level (lost on No. 61) and three windows across on the upper two floors.

53-57 Blenheim Crescent. No. 53 is both lower and set further forward than its neighbours. Note the single plus double windows at first and second floor level of Nos. 55-57. (Photo 2008)

In early 1968, Marc Bolan (1947-77), one of the foremost British musicians of the early 1970s, moved with his girlfriend (later wife Jane) in to an attic flat at No. 57. The flat had no hot water. An artist friend painted a tyrannosaurus rex (the name of his rock band) on the wall. As he became more successful, he moved down to a more luxurious flat on second floor, which he called his chateau – although he allegedly continued to eat macrobiotic food sitting on floor cross-legged and his girlfriend Jane had to sell lampshades on the Portobello Road to make ends meet. He moved out of No. 57 in 1971. [Source: The Hill, March 2013].

- Nos. 63-73 have coursed half-stucco and pillared porticoes with classical decoration. Nos. 65, 67, 71 and 73 have beading or dentelle work below the cornices above their porches and bow windows. Presumably Nos. 63 and 69 once had similar decoration. On the rear, these houses have plain brick elevations with bow windows.

Nos. 65-67 Blenheim Crescent with their typical pillared porticoes. André Derain, the Fauve painter, stayed at No. 65 when he came to London in 1906. (Photo 2008)

- Nos. 75-77 were constructed by builders Alfred and John Secrett, again granted building leases in 1863. These two houses are similar to May’s neighbouring range, with double windows at first and second floor level but without porticoes. Instead they have handsome brackets supporting roofs over the doors and egg-and-dart moulding around the door. Their backs are slightly differently arranged, with only two windows at the level of the upper floors.

- Nos. 79-81 were entrusted to a builder called John Scoley, who was also responsible for some of the houses in Cornwall Crescent. These two houses could be from another street, with rounded arches above the windows and doorway at ground floor level, although they keep the pattern of half stucco. They probably date from 1863 or 1864, and seem to have been a later infill between the terraces on either side. The backs have better decoration round their upper windows and proper cornices. The gap that allows access from the street to the communal garden (which retains its original gate and railings) lies between Nos. 81 and 83 (there is another gate into the garden from Ladbroke Grove).

- Nos. 75-77 were constructed by builders Alfred and John Secrett, again granted building leases in 1863. These two houses are similar to May’s neighbouring range, with double windows at first and second floor level but without porches. Instead they have handsome decorated brackets supporting roofs over the doors and pretty egg-and-dart moulding around the door. Their backs are slightly differently arranged, with only two windows at the level of the upper floors.

- Nos. 79-81 were entrusted to a builder called John Scoley, who was also responsible for some of the houses in Cornwall Crescent. These two houses could be from another street, with rounded arches above the windows and doorway at ground floor level, although they keep the pattern of half stucco. They probably date from 1863 or 1864, and seem to have been a later infill between the terraces on either side. . No. 79 has a curious double window above its door; probably a later alteration.The rear elevations have better decoration round their upper windows and proper cornices than their neighbours. The backs have better decoration round their upper windows and proper cornices. The gap that allows access from the street to the communal garden (which retains its original gate and railings) separates this terrace from the next one.

- Nos. 83-85: Charles Chambers appears to have been the undertaker for these two houses; he was granted building leases by Blake in 1862. Blake also granted leases in 1862 for Nos. 87-91, to Henry Heard, a licensed victualler, in 1862. Both ranges are similar to Nos. 63-77 with half stucco and classical porches, but have an elegant string course below their cornices (similar to those at 21-55 Ladbroke Road) and no bow windows. They are among the most handsome houses on the street. The backs mostly have bow windows and some have cornices.

85-87 Blenheim Crescent, part of one of the best of the ranges on the south side, probably erected in 1862. There is an interesting open parapet cornice, unfortunately lost on No. 85. (Photograph 2008)

- Nos. 93-115 were the responsibility of a builder called Thomas Wesson, who was granted building leases in 1861-2. These were complete or nearly by the time of the 1863 Ordnance Survey map, as they are shown on it.

- Nos 117-127 were undertaken by a builder called Benjamin Reynolds and Nos. 129-135 by Thomas Wesson. Both were granted leases in 1861. There is little or no difference between the two sets of houses, and it seems likely that they were built together as the first range to be erected on this side of the street. The terrace is both plainer and lower than its neighbours to the east, while retaining many of the same decorative features, including the classical porches. The houses completely lack cornices. Behind, they lack the bow windows of their neighbours.

Nos. 129, 131, 133 and 135 have no decoration on the architraves of their porches, but this may well have been their original state.

There is a plaque on No. 115 recording that from 1962-82 it was the home of the Rev. Bruce Kenrick, the founder of the Notting Hill Housing Trust during the Rachman years, and also of Shelter.

85-87 Blenheim Crescent, part of one of the best of the ranges on the south side, probably erected in 1862. There is an interesting open parapet cornice, unfortunately lost on No. 85. (Photograph 2008)

The final house on this side, No. 137 (also known as Blenheim Villa or Blenheim House), is set well back from the road in a large triangular plot. A firm of architects seeking planning permission in 1980s suggested to the Council that this house was built in 1840, well before the rest of the street, on the edge of the Hippodrome Racecourse to serve as a turnstile for race-goers entering the racecourse area. However, the house is not mentioned in the Survey of London and does not show up on maps of the Hippodrome. What is more certain is that Blake acquired the plot on which No. 137 stands, with or without the house, along with the rest of the land that he bought to build Blenheim Crescent. He sold the freehold of No. 137 in 1862 to his partner Charles Chambers, and it seems more likely that the house was built by Chambers in the early 1860s (it appears on the 1863 Ordnance survey map). Chambers chose this attractive two-storey house as his residence: he is recorded as living there in the 1871 census returns, described as a retired builder, living with his wife, two daughters and one servant; and he was still there in 1891.

Sometime in the early 1900s, the building ceased to be residential. It was first occupied by the Welbecson Press, which specialised in horse-racing publications. From about 1937, the property appears to have become a book-bindery. After the Second World War, the premises were acquired by a property company called Victoria Investments. They and their successors leased the premises out to small businesses for a variety of light industrial, office and warehouse use. By the 1950s, several one-story extensions had been built, including a long low building between the house and the road, and there were usually two or three different concerns operating from the premises, employing 20-30 people. In the 1980s, tenants included Rough Trade Records, a small local record company (and there was a large sign on the front building saying “Hot Lips”). The commercial users did not have a right of access to the communal gardens, and there were lengthy hostilities between the owners and the garden committee in the 1980s over a gate that the owners had built in the back wall.

Later in the 1980s, the building in front of the house was demolished, but the back extension, known locally as “the factory”, remains. By 2000, the property company then owning the house decided to convert it back to a single residence and it is now a private house again.

Strangely, it appears to have no Article 4 direction. Although it has no doubt been significantly remodelled over the years, it is a handsome building and merits care.

137 Blenheim Crescent. © Thomas Erskine 2006

Listings and other designations All except No 137 have Article 4 directions requiring planning permission for:

Nos. 55-135 (all houses backing onto a communal garden) have Article 4 Directions requiring planning permission for alterations to the rear of the house. Nos. 81 and 83, on either side of the street entrance to the communal garden, have Article 4 directions applying to their sides as well. The rears are classified as “important rear elevations” in the Conservation Area Proposals Statement of 1976 (as updated in 1989). Nos. 55-72 have Category 2 rooflines; and Nos. 83-135 have Category 1 rooflines. The gap between Nos. 81 and 83 is also categorised as an “important gap”. |

Recommendations to householders and planners Porches: Most of the houses in these ranges have kept their detailing well. But several houses (Nos. 55, 65, 67, 69, 107, 129 and 131) have lost the triglyph decoration on the architraves of their porches. This could easily be reinstated. Cornices: Nos. 57-61 have lost the little brackets under their cornices (still mostly there on No. 55). We hope these will be restored some day.

Nos. 83-115 have or had elegant string courses below their cornices which are particularly worth preserving or restoring where they are missing (on Nos. 85, 93, 99, 109, 111, 113 and 115).

Missing string course on left hand house

Brickwork: Nos. 55-61 have all had their brickwork painted over, which is a pity but at least they are uniformly painted. Nos 91 and 127 have also had their brickwork painted or rendered, to the detriment of the terrace, and it is to be hoped that one day the paint or render will be removed, and that no more of the half stucco houses will be painted. Windows: The decoration on the windows of the two upper floors of Nos. 117 and 125has been largely lost (and partly lost from the top floor of No. 127) and it is to be hoped that this will be restored to match the neighbours one day. Railings and ironwork: Nos. 83-135 have or had rather attractive railings up their front steps and on the sides of their porches. Where they have been lost, their reinstatement would be welcome. The street railings were mostly removed during the war and replaced on only some houses. A few houses still have their original pot-guards on their ground floor window sills, and the restoration of these on the others would also improve the street. No. 107 has an unsightly painted brick wall on its boundary with the highway. We hope that one day the traditional railings will be reinstated. Front steps: Several of these houses have unsightly droopy asphalt on their front steps.We hope that this will be covered in stone or tiles. Rear elevations

|

Blenheim Crescent west of Ladbroke Grove: north side (36-94 evens)

In 1863-4 Charles Blake granted building leases to at least four different undertakers for the north side, again leading to a number of different styles. Whereas on the south side the different terraces consist just of rows of virtually identical houses, on the north side two of the builders erected ranges in which the ends of the terraces are marked by houses slightly different from their peers, forming a symmetrical ensemble.

No 36, on the corner of Ladbroke Grove, is an interesting double house, with another entrance to a separate dwelling round the corner at 95 Ladbroke Grove. The house was built by the architect George Drew, the son of William Drew who had been earlier responsible for developing much of the southern end of Ladbroke Grove. George Drew obtained his building leases for this house and the neighbouring ones in Ladbroke Grove in 1864 (when the house was numbered 1 Ladbroke Grove North). The ground rent was £11.14s. There are documents relating to the house in the Local Studies section of Kensington Public Library (Nos. 478-489) showing that in the 1870s and 1880s the house was known as Beresford House. By 1875, E. Y Western (who had already acquired Drew’s original 99-year original lease) purchased the freehold for £320, thus reuniting leasehold and freehold. The documents include a large poster advertising the house for sale in 1887, suggesting it would command a rent of £95 per annum if it were let. The house is described as “of very imposing elevation and conveniently placed, entertaining good accommodation, hot and cold bath, tiled lobby, stone staircase etc. From the commanding position of the Property, it is eminently suitable for the requirements of a professional man”.

The next two houses, Nos. 38 and 40, are among the most elegant in the street. Street. Both are detached and identical in decoration, but curiously No. 38 is single fronted and No. 40 double-fronted. Perhaps they were originally intended as part of a terrace. Blake seems to have disposed of his freehold interest in houses in Blenheim Crescent fairly early on, for financial reasons, and the freeholds probably changed hands between various investors a number of times before being acquired by the owners of the houses in the mid-20th century. A deed survives in the Kensington Local Studies Library which shows that in 1907 the freeholds of Nos. 38 and 40 and Nos. 62-82 Blenheim Crescent belonged to one John Ashley Mullens Esq. of Chertsey, probably a gentleman of means for whom the freeholds were just part of an investment portfolio. He sold them to another investor living in Paignton, Devon, for a total of £2,720

No. 40 Blenheim Crescent, an elegant double-fronted house. It was at one time known as Fairlight Villa

Between St Mark’s Road and St Mark’s Place there are two adjoining symmetrical terraces of five houses each, at Nos. 42-50 and 52-60. The two end houses of both terraces are set slightly forward and have slightly different decoration.. The pediments of end houses of the slightly lower second terrace are surmounted by handsome stucco balustrades. This terrace also has interesting detailing around the windows. No. 42 has its door round the corner in St Mark’s Place, and the door of No. 60 is in St Mark’s Road.

Nos.52-60 Blenheim Crescent, showing the roof balus- trading on the end houses. Photo 2008

Detail of a window at No. 52. Photo 2008

The undertaker for Nos. 62-66 was J. S. C. Small, a plasterer, who was granted leases in 1863. Alone of the builders of the houses in this part of the street, he – or more probably a later occupant – indulged in a flight of fancy in the form of a high corner turret on No. 62 (which again has its front door on the side in St Mark’s Road).

No. 62 Blenheim Crescent with its curious corner turret. © Thomas Erskine 2006

Leases were also granted in 1863 for Nos. 68-78 to the builder Thomas Wesson and for Nos. 80 and 82 to another builder, John Burton of Cornhill. The two obviously collaborated, as these houses are of the same design, making up an unadorned terrace of half stucco houses with three floors plus basements.

Blake also granted leases in 1863 to Thomas Wesson for Nos. 92-98. Nothing now remains, however, of the originals at 84-98. Nos. 96 and 98 suffered bomb damage in the Second World War and were demolished, to be replaced in the 1950s by the present modern four-storey block of flats (outside the Ladbroke conservation area). Originally, a detached villa, Blenheim House or No. 100, stood at the end of the terrace. An interesting 1928 deed survives in the Kensington and Chelsea Local Studies library which mentions the original 99-year lease of this house granted by Charles Blake in 1861 to Edmund Cordery, the Bayswater builder who had erected it, at an annual ground rent of £3. The deed records the way that the lease (and its valuable rental income) was then “assigned” (bought and sold) several times between 1861 and 1928. This house was typical in the way that the freehold was owned by one investor and the 99-year lease by another who then sublet the property to the actual occupant (sometimes yet another layer was added, as the owner of the 99-year lease would grant a shorter – say 21-year – sub-lease to yet another investor who then rented the property out). One investor in freeholds was the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, who acquired the freeholds of Nos. 96 and 98 in 1865 and used them to endow the benefice of St Michael’s, Sutton.

Nos. 84-94 survived the war. In 1986, the Kensington Housing Trust, which had acquired the whole block, obtained planning permission to demolish these six houses and to replace them by the present three double-fronted houses (each with two street numbers) with a total of 21 living units. Predictably, there was strong resistance from the by then increasingly middle class residents of the road to the demolition of a not particularly distinguished but nevertheless pleasant Victorian terrace in keeping with the rest of the street, and one group of residents even tried to buy the block. Although the houses were thought to be structurally sound, they were probably pretty dilapidated as squatters had moved in. But it seems that the Trust decided on demolition and rebuilding chiefly because much bigger Council grants were available for that than for refurbishment. This was a sad act of vandalism; while the new block was built to blend in with the rest of the street, it is clearly a recent addition of unfortunately uninspired architecture. As the Ladbroke Association commented at the time, the porches are particularly clumsy.

Listings and other designations None of these buildings is listed. Nos. 36-94 evens are subject to Article 4 Directions that mean planning permission is required for:

Recommendations for new Article 4 Directions We recommend that the Article 4 Directions applying to the front of these houses be extended to cover the entire front elevation to give some protection to brickwork and important features such as cornices. |

Recommendations to householders and planners There has been painting over of brickwork at No. 82. We hope that the paint will one day be removed and that no further brickwork on these handsome half-stucco houses is painted over. Some houses (Nos. 68 and 70) are missing the decoration on their porches. We hope that this will one day be restored. Nos. 42-60 evens have good rooflines.Although No. 56 has had two dormer windows added, these are barely visible from the road. No futher dormers should be permitted on these two ranges unless they are equally invisible. The cornices of several of these houses could also do with some restitution.

|