Keeping the Ladbroke area special

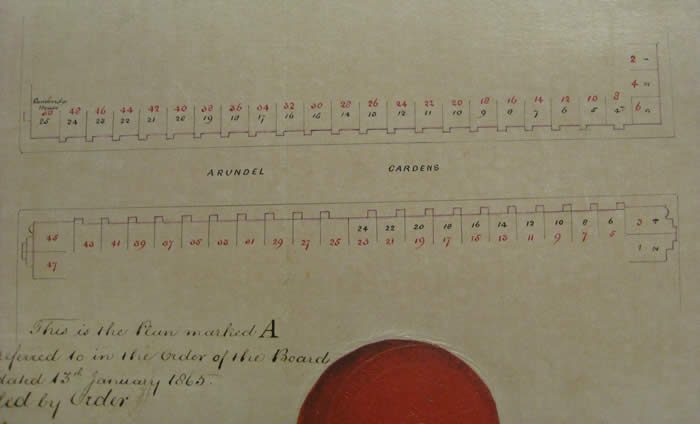

A Metropolitan Board of Works plan showing how the houses were renumbered in 1863.

All the new numbers are in red.

Arundel Gardens

History

Arundel Gardens was built towards the end of the development of the Ladbroke Estate, in the early 1860s. By the 1850s, the Ladbroke family was beginning to sell off freehold parcels of undeveloped land. One of these consisted of the land between the south side of Arundel Gardens and the north side of Ladbroke Gardens. This was acquired in 1852 by Richard Roy, a solicitor who had already been involved in building speculation in Cheltenham. He appears to have done nothing with the Arundel Gardens part of his land until 1862-3, when building leases were granted for the houses on the south side (numbers 1-47) – 21 of the 24 leases were taken by a builder called William Wheeler who had previously built the houses in Horbury Crescent; 21-55 odds Ladbroke Road; and 4-17 Ladbroke Square. Around the same time, leases were granted to three other builders to build houses on the north side (Edwin Ware for Nos. 2-14). The survey done by the Ordnance Survey in 1863 shows that the south side was complete by then, but only a few houses had been built on the north side, at the Kensington Park Road end. Building clearly proceeded apace, however, as an 1865 plan, done when the street was given its current name and numbers (it was originally called Lansdowne Road Terrace), shows that all the houses were complete by then. The building was not without accidents: a letter in the Times records that in 1865, when work was still being done on the interior of the houses at the Lansdowne Road end, a young boy living at 97 Lansdowne Road died when he fell into a temporary well built by the workmen under the pavement. There were also early problems with flooding. In 1888, a deputation from Arundel Gardens pressed the Metropolitan Board of Works to enquire into the flooding of over-charged main sewers.

A Metropolitan Board of Works plan showing how the houses were renumbered in 1863. The new numbers are in red.

As often on the Ladbroke estate, the ends of both the south and north terraces turn the corner into the neighbouring streets, thus making a tidy end to the terrace. So numbers 1 and 3; and 2, 4 and 6 are in Kensington Park Road and No. 50 (Cambridge House) and now also No. 52 (Arundel House) are in Ladbroke Grove.

From the beginning, the houses came with access to the communal “pleasure gardens”. In 1862, according to a deed in the London Metropolitan Archives, Richard Roy granted a 2,000 year lease of the land on the south side “to be used or enjoyed thenceforth during the said term as a pleasure garden in proper ornamental cultivation and condition for the exclusive use and benefit of the several freeholders and leaseholders and their several tenants and occupiers for the time being of the messsuages or tenements forming or being part of Ladbroke Gardens and Lansdowne Road Terrace and the respective families and servants of such owners and occupiers and their respective friends in their company”. The householders paid a guinea (£1.10) a year towards the cost of the garden.

The houses were built for single occupation. By the time of the 1871 census, all were occupied, almost all by families with two or three servants. The heads of household included lawyers, merchants, Indian Army officers and other typical middle class professionals, along with a fair number of widows living on annuities. There were quite a few foreigners: for instance a German bank director at No. 3; a Polish merchant at No. 7; a Panamanian merchant at No. 27; and a Major on the Imperial Prussian Staff at No. 32. The arts were represented by a professor of music at No. 36 and a painter, Anthony Montalba (1813-1884) at No. 19 . Montalba had five children living with him. Four daughters became successful artists in their own right – the best known being the sculptor Henrietta Montalba, who merits an entry in the Dictonay of National Biography. A distinguished naval medical officer who was honorary physician to the Queen, Sir Edward Hilditch (1805-1876), lived with his family at No. 18. There was a small boarding school at No. 14. Slightly later, another famous inhabitant was the scientist Sir William Ramsay (1852-1916), who discovered the noble gases and lived at 12 Arundel Gardens. A blue plaque has been put up on the house to commemorate his residence there. Charles Samuel Myers (1873-1946), the psychologist who coined the term “shell-shock” lived at No 27 Arundel Gardens as a boy.

Most residents were tenants, paying rents to the builders of the houses. The Local Studies Library has a document dating back to 1863 for No. 18 Arundel Gardens. Frederick Farrar and others (who under complicated financial arrangements had between them the beneficial interest in the land on which the house was built) leased the land and the newly built house on it to Edwin Ware, the builder who had just erected it, for a term of 97 years. The rent was £4.15s in the first year and thereafter £10.10 a year. They also paid him £95 towards the cost of the house. He was required to complete the work on the house in such a way that it had a value of £1,000, and there were also detailed clauses on how often it needed to be painted inside and out, etc., during the term of the lease. This lease was a fairly usual arrangement for the time. The freeholders got an annual income for a very small outlay; and the builder made his profit by letting the completed house for a lot more than the ground rent.

Some of the properties were sold on fairly quickly by their original owners as the builders needed money for new works or to pay off mortgages. An 1870s estate agent’s prospectus in the London Metropolitan Archives describes Nos. 31, 33 and 35 Arundel Gardens as “four well-built freehold residences to be sold for investment, all let to first class tenants at rents of £120, £110, and £115 respectively”. No. 29 was being sold at the same time for “occupation or investment”. The price asked was £2,100 each. The seller was probably the builder William Wheeler, who built 21 of the 24 houses on the south side. There are deeds relating to the sale of No. 35 in the Archives; it seems ultimately to have been sold in 1778 by Wheeler’s estate for £1,900 to its then occupant, Charles Edward McKenna.

An early annoyance for residents seems to have been organ-grinders. According to a report in the Times, an Italian organ-grinder was arrested in 1864 because of complaints by local residents, including Mr B.C. Jones of 9 Arundel Gardens who was engaged on writing an historical work, that they were being regularly disturbed by his playing.

According to the Kensington and Chelsea Community History Group’s website historytalk.org, at the beginning of the First World War, Arundel Gardens was hit by a bomb from a Zeppelin. The locals believed that the German manager of the Electric Cinema was signalling to the Zeppelins from the roof, and the cinema was attacked by an angry mob.

There were still prosperous families living in Arundel Gardens in the first part of the 20th century, judging by an advertisement in the Times in 1914 by Mrs Brock Hunt of 5 Arundel Gardens: “Wanted immediately: good plain COOK, wages £24. 2 in family, 3 servants. Must be Church of England”. But prices were lower than in the 19th century: The Times reported that in that year Mssrs John Barker bought No 41 for £1,500.

As the 20th century advanced the street went gradually down hill, with the houses increasingly entering into multi-occupation. By the 1950s, pretty well all the houses were in multi-occupation – mostly slummy bed-sits. Most were in pretty poor condition, and at least one was uninhabitable – a report in 1952 recorded that No. 4, which had been requisitioned by the Council during the War and only released in 1950, was vacant and unfit for habitation as it had no electricity, no plumbing and no sanitation. During this period, sadly, some of the stucco detailing was lost. Unfortunately, a lot of the fine cornices within the buildings have also disappeared, although many remain.

Since the 1950s, the street has gradually come up in the world. During the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, the houses were gradually converted into self-contained flats and maisonettes, and some houses are now back in single occupation. Happily, some of the lost detailing is being restored. Most buildings have had extra mansard stories added. As the houses were built with four storeys plus a basement, this means that six floors is now the norm. All the houses have good ironwork on the first floor balconies and handsome uniform railings. The ironwork on the first floor balconies is reproduced as banisters inside the houses.

The Greater London Council’s Survey of London is less than complimentary about the architecture of Arundel Gardens, which it sees as representing a marked decline from the elegance of earlier parts of the Ladbroke Estate. The street is described as consisting of “dull four-story ranges, that on the north side being faced with stucco and that on the south side being of stock brick with coarse flamboyant stucco enrichments”. Nevertheless, the uniformity of the terraces gives the street a certain grandeur; as does its alignment on a vista of the handsome central houses of Kensington Park Terrace North.

South side (odd numbers): architecture

The houses on the southern side all have stucco on the ground floor and London stock brick with stucco detailing on the upper floors (including a string course and a cornice supported by brackets) and pillared porches. The terrace was originally buttressed at the eastern end by two houses with their entrances in Kensington Park Road, and at the western end by two with entrances in Ladbroke Grove. Those at the Kensington Park Road end (Nos. 1 and 3) remain. Those at the Ladbroke Grove end (Nos. 45 and 47) along with the first house on Arundel Gardens proper, No. 43, were a particularly notorious example of multi-occupation and fell into such a state of disrepair that they were demolished in the 1960s and replaced by a modern block of flats, Arundel Court.

The terrace was built to a strictly symmetrical pattern. The houses buttressing the terrace at either end had extra decorative worming in the stucco at ground floor level and big three-light windows on the upper floors. This pattern was replicated in the first two houses at either end of the terrace in Arundel Gardens proper (Nos. 5-7 odds at the eastern end but now only No 41 at the western end). The four houses in the centre of the terrace (Nos. 21-27 odds) also have the same pattern.

The intervening houses (nos. 9-19 and 29-39) are simpler and have two single light windows on the upper floors. These houses largely maintain their original appearance. Unfortunately, however, the symmetry has been spoilt by the fact that four of the houses have had their brickwork painted over, and several of the cornices are missing.

Nos. 1 and 3, in Kensington Park Road, have bow windows (as probably did their fellows at the now demolished Nos. 45 and 47). They also have a curious and rather ugly two storey extension over their porches. This extension does not appear on the 1863 Ordnance Survey map, but seems to be there by the time of the 1890s map, so it was presumably added fairly shortly after the houses were built (this is borne out by the way the cornices extend within the building). The second half of the 20th century unfortunately saw the painting of the brickwork on No.1 and the acquisition of an unsympathetic and obtrusive extra top floor over both houses. Many of the other houses in the street also now have extra storeys, but they tend to be fairly discreet mansard additions.

Two of the four houses at the centre of the southern terrace with three light windows. To the left and right the houses have two single light windows (photo 2007)

The backs of the houses look onto the communal Arundel and Ladbroke Garden, and are of relatively unadorned brick, with stucco at ground floor level. Most of the windows and doors on the backs have been substantially altered. Judging by the remains on some of the houses, at ground floor level there were a large window, a door and next to the door a small window with a semi-circular moulding. At first floor, the same semi-circular pattern was repeated in a slightly larger two-light window. The houses have happily almost all retained their cornices at roof level.

A few of the houses have gained rear extensions, mainly small single floor ones, although two at the western end have rather unfortunate two-floor extensions, and in one case (No. 33) the brickwork has been painted. The houses have their own gardens, separated from the communal garden and each other by low iron railings. This gives the whole complex an attractive open look, with private gardens melding into the communal gardens. In some cases, wooden stockades have been built, to the detriment of the open aspect.

Two of the four houses at the centre of the southern terrace with three light windows. To the left and right the houses have two single light windows (photo 2007)

There are a number of early deeds relating to No. 35 in the London Metropolitan Archives.

South side: Article 4 Directions and listings None of the buildings in the street is listed, although the communal gardens on both sides are Grade II listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.. There are Article 4 directions on the fronts of the houses:

|

SOUTH SIDE d(odd numbers): recommendations to planners and householders on features that should be retained, protected, restored, encouraged or discouraged. To preserve and enhance the character of the street and the communal garden, the Ladbroke Association would urge all householders to consider following the guidelines below.

South side rear elevations

Original windows on a rear elevation

Original railing and gate

|

This terrace is entirely stuccoed and the houses are separated by rustication. There is not the same systematic symmetry as on the south aside. No.8 has three bays; all the rest have two. Nos. 8 and 10 at the east end; 22-30 odds in the middle; and 44, 46, 48 at the west end are set very slightly forward of the others, but so little as hardly to be more than an echo of the bookends and central palace front block common in Labroke estate terraces.

Nos. 2, 4 and 6, around the corner in Kensington Park Gardens, form a handsome symmetrical group of their own, the two outer three-bay houses framing a two-bay house with slightly differing detailing. No. 6 has a largely blank side wall on its Arundel Gardens side, but with interesting stucco decoration.

Nos. 2,4 and 6 in Kensington Park Road (copyright Thomas Erskine 2006)

No. 8, the first house in Arundel Gardens proper, also has three bays. Unfortunately, its original pillared porch has been replaced by an ugly box-like one (as also on No. 18). Nos. 10-48 all have two bays. The decoration on these houses is not unattractive and includes a string course above the second floor and cornices with brackets matching those on the southern side (at any rate on Nos. 24-48; it is not clear whether the lighter grooved cornicing on the eastern end of the terrace is original, but it may well be). As on the other side, the terrace is marred by the loss of cornices on many of the houses. There was also worming decoration around the windows and on the porches; unfortunately much of this has also been lost.

Nos. 2, 4 and 6 in Kensington Park Road (copyright Thomas Erskine 2006)

At the western end, there are two houses round the corner in Ladbroke Grove belonging to Arundel Gardens, Nos. 50 and 52. No. 50 (Cambridge House) was built around 1863 and acquired a rather over-elaborate porch with floors above, the 1867 plans for which are in the RBKC Public Library (MBW/1867/6). Before then, there was a gap where the porch now is and the front door of Cambridge House was in the middle of the Ladbroke Grove elevation where there is now a projecting window. The plans for the new porch show only one floor above it; so they were either amended before construction or the second floor was added later.

No. 52 (Arundel House) was probably built a few years later (it is shown on the 1867 plan for No. 50’s new porch). It rather awkwardly blocks the light from the backs of Nos. 48 and 50 and is in a different style and altogether somewhat mysterious.

Both have at various times been treated as part of Ladbroke Grove. In 1875, Cambridge House was known as “70 ½ Ladbroke Grove”, and there is an order in that year by the parish authorities that it should thenceforth be numbered 50 Arundel Gardens. Arundel House was for a long time “No. 70A Ladbroke Grove”; it was only in 1997 that it became 52 Arundel Gardens.

Arundel House (left) and Cambridge house, both facing onto Ladbroke Grove (copyright Thomas Erskine 2006)

The backs of the houses look onto the Arundel and Elgin communal garden, each house having its own private garden opening onto the communal garden. Originally all would have had railings between the private gardens and the communal garden, and some of the original railings are still there. The backs are plain London stock brick, none of which has been painted over. The old maps indicate that Nos. 10-22 were probably built with closet wings (although probably not beyond first or second floor level) and most of the other houses have acquired them since (the 1893 map shows the others as having flat backs – as is still the case for No. 44 – or small privy-type extensions). The general effect is not unpleasant, although some have been somewhat oddly designed and that on No. 16 is obtrusively large and detracts from the look of these backs. Where extensions have been extended over the whole width of the building (as is the case for No. 38) and are constructed of non-matching materials, it also detracts from the look of the terrace.

Rear elevations of the north side of Arundel Gardens

North side: Existing Article 4 Directions and listings None of the buildings in the street is listed, although the communal gardens on both sides are Grade II listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.. There are Article 4 directions on the fronts of the houses:

In addition, there are a number of restrictions on what can be done to the rear of the houses without planning permission. Planning permission is needed for:

We are concerned that the present Article 4 directions may not give sufficient protection to the sides of some of the end buildings, or to features such as ironwork, string courses and cornices. We would recommend that Directions be considered for the following:

|

North side: recommendations to planners and householders on features that should be retained, protected, restored, encouraged or discouraged. To preserve and enhance the character of the street, the Ladbroke Association would urge all householders to consider following the guidelines below.

Rear elevations

|

As the houses have no front gardens, their coal-cellars were built under the pavement. Many of the original coal-plates covering the holes through which the coal was delivered have survived. There are 11 in the pavement on the south side and 14 on the north side. Coal-plates were made by a variety of small foundries, each of which had its own patterns, and a variety of patterns are represented in Arundel Gardens.

|  |

|  |

Vista: The street’s greatest asset is arguably its vista towards the central houses of “Kensington Park Terrace North”. This vista should be preserved. Recently the Council planted magnolia grandiflora along the street. As they grow, it will be important to keep them sufficiently pruned to stop the view being blocked.

There is more on the history of the street and the communal gardens on the Arundel and Ladbroke Gardens website www.arundelladbrokegardens.co.uk.

All photographs (except where otherwise stated) are the copyright of Thomas Erskine and were taken between 2004 and 2007.

Sources include the Survey of London; census returns; The Times digital archive; documents in the RBKC Local Studies Library and the London Metropolitan Archives; RBKC planning archives; stories by local residents.

Page last updated 30.6.2023