Keeping the Ladbroke area special

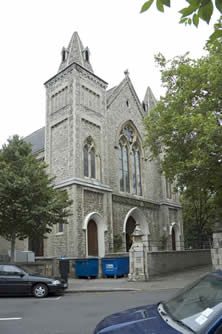

St Peter’s Church, Kensington Park Road. Photo: Thomas Erskine 2006

Religious buildings

The two Church of England churches on the Ladbroke estate can be said to be designer churches specially constructed as an integral part of the estate – St John’s on top of the hill in Ladbroke Grove is the centrepiece of the estate; and St Peter’s in Kensington Park Road completes a stunning view down Stanley Gardens. Kensington Temple (or KT) at the angle of Ladbroke Road and Kensington Park Road, originally the Congregational Horbury Chapel, was built a bit later and is now a very well-frequented Elim Pentecostal Church. Then near the other end of Kensington Park Road is the Peniel Chapel, now the Notting Hill Community Church. In days gone by, however, there were at least four other religious establishments in the area, including a large Catholic convent and a synagogue. The following are notes on some of these establishments, past and present.

St John's Church

The church of St John the Evangelist at the top of Ladbroke Grove was deliberately sited to form the centrepiece of the Ladbroke estate. It was built in 1845, just when the second great wave of building on the estate was beginning, and the developers no doubt hoped that the proximity of this handsome Victorian gothic building would enhance property values in the area.

The first wave of building had taken place in the 1820s, along Holland Park Avenue and neighbouring streets. A financial downturn brought it to an end in around 1830, and the undeveloped area to the north was let to an entrepreneur who used it to build a race-course, the Hippodrome. Where St John’s now stands was the highest point and served as a natural grandstand for the race-goers. But the race-course was not a success, not least because of the heavy clay soil, and by the end of the 1830s the operator of the race-course relinquished his lease on the land round St John’s, just as the demand for new housing was picking up. The Ladbroke family then gave leases of the land to a variety of developers, and building began again in the early 1840s.

The building of the church followed a petition by the Vicar of St Mary Abbots to build another church in his parish as the existing churches were ‘inadequate to accommodate the inhabitants’. There seems to have been quite a lot of competition among the developers to have the church built on their land, with competing sites being proposed on either side of Ladbroke Grove. In the end, a piece of ground on the western side (known as “Hilly Field”) was donated by both Robert Roy, the developer of the area west of Ladbroke Grove. Probably as a quid pro quo, it was agreed that one of the architects should be John Hargrave Stevens (1805/6-1857), who was involved in the development of the eastern side.

The total cost was just over £10,000. About half of this was raised by private subscription, a favourite way of raising funds for buildings of public benefit in the Victorian era. The rest came from the developers, including a loan of £2,000 from Charles Blake, another of the speculators active in the area; and another from the Victorian statesmanViscount Canning, who made loans to the builders of the Ladbroke estate as a form of investment.

The builders chose a 13th century Early English style for their church – rather curiously, as the prevailing style of the Ladbroke estate is classical and the Victorian gothic revival movement was only just beginning. The spire is very similar to that of the Early English St Mary’s church in Witney, Oxfordshire. Pevsner describes the church somewhat severely as “architecturally undistinguished but archaeologically correct”. The east end of the church was designed to close the vista at the end of Kensington Park Gardens, on which construction had just begun. It was built to accommodate a congregation of 1,500 (in the aisles and in galleries above them), of whom 1,100 were to be for worshippers paying pew rent and 400 were to be “free sitting”. Its vicarage was erected next to the church at what is now 63 Ladbroke Grove, also built in a somewhat gothic style. The church was listed Grade II in 1969.

63 Ladbroke Grove, which used to be the Vicarage. ©Thomas Erskine

The timber roof beams of its interior originally had painted symbols of the four Evangelists and scrolls with quotations from the scriptures. No trace of these now remains. Some of the original Victorian stained glass windows survive, including one designed by William Warrington (1796-1869), one of the foremost producers of stained glass for the gothic revival movement. An elaborate carved reredos was added behind the altar in 1890, designed by the well-known late Victorian architect Sir Aston Webb (his works include the main building of the Victoria and Albert Museum, part of Buckingham Palace and Admiralty Arch). So distinguished people were involved in providing the fittings.

There were originally plans to install a specially designed organ. But financial problems led to a decision to purchase a second hand organ, from Holy Trinity Church, Clapham Common. It had been built in 1794, and various alterations were made to bring it in line with Victorian taste, including the replacement of the original classical case by a gothic one (now lost). It still operates today and has just been given a major renovation. It is rare to find an instrument with both Georgian and Victorian features, and the organ has been given a Grade II* listing under the Historic Organ Certificate Scheme.

To begin with, St John’s was still largely surrounded by open country. The only houses nearby were what are now 2-4 Lansdowne Crescent and the terrace at Nos. 37-57 Ladbroke Grove The church was known locally as the Hippodrome Church or St John’s in the hayfields. Within very few years, however, it was largely surrounded by newly built houses.

Over the years a number of changes were made to the church to accommodate changing needs. For instance, in 1883, it was agreed ‘by a large majority of the congregation that a more zealous and religious feeling would be imparted to the services’ if the men and boys of the choir wore surplices. However, the vestry did not have enough space for the clergy and choir to robe together before services, so some seats in one of the galleries were removed, it being argued that they were located so that it was ‘difficult for occupants to see the pulpit or hear’, and a new clergy vestry created. In 1929, more galleries were removed, reducing the seating to 838, which was deemed by then “amply sufficient for the needs of the church.”

In 1942, the top of the steeple was removed by Government order, as it was considered a hazard to low-flying aircraft. The topless steeple became a well-known post-war land-mark until it was rebuilt in 1957.

One of the biggest changes has occurred in more recent years, with the structurally ambitious building of a large undercroft under the church to provide a parish office and activities centre. It now also houses a nursery, the Monkey Puzzle, which has its own entrance. The church is currently (2014) undertaking a big renovation of its interior, including the restoration of many original features and internal decoration.

The activities that take place in the church are now wide-ranging. Apart from daily services, there are regular classical concerts, as well as talks, films, exhibitions and workshops. Like many London churches, St John allows other denominations to celebrate services there. For 10 years it hosted services for the Eritrean community, but the Eritreans have moved elsewhere as they are now too numerous to be accommodated there. St John’s is also home to a Filipino Chaplaincy, the Filipinos having overtaken Arabic speakers as the largest non-English-speaking community in the Borough. Services in Tagalog are celebrated by a Filipino priest belonging of the Philippine Independent Church, part of the Old Catholic Federation (in communion with the Church of England), but the services are ecumenical with all Christian denominations welcome. Filipinos apparently come from all over London to attend. Services are also planned for Korean Christians.

Inside the church, around the organ, an excellent exhibition of the history of Notting Hill has recently been installed, which is well worth inspecting. The church is open from 10 until 1 o’clock every day. Its website is www.stjohnsnottinghill.com. The website includes a detailed scholarly history of the church, from which parts of this article have been drawn.

This is an edited version of an article that appeared in the autumn 2014 edition of the Association’s newsletter News from Ladbroke.

St Peter's Church

Historical notes by Leslie du Cane (1997)

During the rapid development in the 1840s and early 1850s on Ladbroke’s Kensington Park estate, it became clear very soon after St. John’s Church was opened in 1845, that an additional church was needed in the area. The site for the new church was presented by Charles Henry Blake Esquire (1794-1872), the area’s most successful property developer. Blake had spent most of his life in Bengal, initially as an indigo planter in the family business, and later as a rum and sugar manufacturer. By 1843 he had retired and come to England. Blake lived at No. 24 Kensington Park Gardens from 1854-1859.

St Peter’s was designed by the architect Thomas Allom, as an integral part of his design for Kensington Park Gardens, Stanlev Crescent and Stanley Gardens. His Ladbroke Estate housing, designed in 1852-3 and St. Peter’s Church are Allom’s principal architectural work. Christchurch (1847-1848) in Highbury is another Allom church. Today, however, AIlom is better known as an artist than as an architect.

The foundation stone of St. Peter’s Church was laid in November 1855 and it was consecrated on 7 January 1857 by the Bishop of London, Archibald Campbell Tait, who was in 1869 to become Archbishop of Canterbury. At the time of its consecration, the church could accommodate 1,400 worshippers. It is probably the last 19th century Church of England church to be built in London In the classical style. The church b a building of exceptional architectural quality and is deservedly listed Grade II*. The magnificent western façade, with its bold pediment and entablature carried on six engaged Corinthian columns is best appreciated from Stanley Gardens. Within, the elegant gallery fronts each contain three panels ornamented with the keys of St. Peter, floral swags and winged putti.

In 1879 the church was enlarged by the addition of an apsidal chancel, which has double arches supported on Corinthian columns of Torquay red marble – these columns cost a mere £48 each! The spandrels of the western arch are ornamented with a beautiful pair of angels bearing gilded trumpets and garlands.

Between 1990 and 1994 a programme of restoration works was carried out restoring the interior at the church. Further restoration and renovation was undertaken in 2010.

Architects:

Church (1857): Thomas Allom (1804-1872)

Chancel (1879): James Edmeston FRIBA FS& (1824-1898) (father) and James Stannlng Edmeston ARIBA (1844-1887) (son).

Chancel/pulpit(1879): Charles Barry FSA FRIBA (1823-1900).

In 1870-1 the Edmestons had been the architects for the “‘Rhineland Romanesque'” St. Michael’s church In Ladbroke Grove. Charles Barry junior was the eldest son of Sir Charles Barry, the architect with Pugin of the Houses of Parliament. Charles Barry Junior was a distinguished architect in his own right. He was President of the RIBA from 1876-1879 and his architectural work included both Dulwlch College (1866-70) and New Burlington House (1869-73) In Piccadilly.

Internal features

SCULPTURE: PULPIT (1879): Thomas Maclean 11845-1894) (The ‘Call of St. Peter’, the ‘Trial of Faith’ and the ‘Charge’).

MONUMENT: SOUTH AISLE: Frances Susanna Addams (1829-1860), sculptor Matthew Noble.

Frances Susanna was the first wife of the first incumbent at St. Peter’s, the Rev Francis Holland Addams (1826 1891). Between January 1860 and January 1862 Addam’s wife and four of his five children died; in February 1862 he resigned his incumbency.

MONUMENT: NORTH AISLE: Louisa Mary Forsyth (1859-1876) & Emily Vesey Dawson HIre Forsyth (1859-1816)

The SS Strathclyde was sailing from London to Bombay, when on 17 February 1876 she was involved in a ‘dreadful collision’ with the SS Franconia about a mile outside Dover harbour, as a result of which she sank within about 10 minutes. 15 of the passengers were drowned, one of whom was a 16 year old girl, Louisa Mary Forsyth.

MONUMENT: NORTH STAIRCASE: Dr John Robbins MS DD FSA (1832-1906) (sculptors: Darsie Rawlins ARCA FRBS & Joan Hassall OBE (1906-1988)

MONUMENT: CHANCEL STEPS: Horatia Nelson Cox (1845-1925) (1st cousin twice removed of Admiral Lord Nelson).

MOSAIC: The wall of the apse is decorated with an important work in Venetian mosaic. The subject is Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Last Supper’ and the work was executed in 1880 by Messrs Burke & Salviati. The copy for the mosaicists was made from the Royal Academy’s copy of da Vinci’s work that made by his pupil, Oggione. The treatment differs from the original in the arrangement of the background, which was designed by CharIes Barry junior to harmonise with the architecture in this part at the church.

STAINED GLASSin the NAVE (c.1860-1880): Artists: John Richard Clayton (1827-1913) & Alfred Bell (1832-1895).

SOUTH CHAPEL/NORTH WAll (1906) & BAPTISTRY (1905): Artist: Arthur J Dix.

The west window (1857) by Henry Fanner was the original east window of the church; it was moved to its present position in 1879 when the apse was constructed. This window’s design is a copy of Raphael’s ‘Feed my Sheep’ cartoon; note that when viewed from the nave, the image is seen back to front!

The Addams memorial windows In the south aisle are important examples of Clayton & Bell’s early work.

The easternmost nave aisle and gallery windows, probably also the work of Clayton and Bell, are memorials to the wives of Thomas Eykyn (1825-1892). The reason that both the gallery windows display the same coat of arms is that his wives were sisters. Jane (1829-1856) and Anne Sarah (1827-1869), daughters of John Gilbert. The Eykyn motto ‘ESSE QUAM VlDERI’ may be translated as ‘To be rather than seem to be’.

ORGAN: Installation (1905-13) J.W. Walter &. Sons (London). Although erected in 1905, it was not until June 1913 that, with the addition of the last nine stops, it was completed according to the original specificatIon. The organ pipes are divided between two organ chambers, sited north and south of the chancel; the action is tubular-pneumatic. The organ was entirely renovated to Its originaI state in 2010 by Andrew Fearn, Organbuilder.

Convent of the Poor Clares

The Monastery of the Poor Clares occupied the block between Westbourne Park Road and Blenheim Crescent to the north and south; and between Kensington Park Road and Ladbroke Grove to the east and west. The convent was established in 1847 at the request of the future Cardinal Manning. At the time that it was built, the site was described in The Building News as a ‘dreary waste of mud and stunted trees’, the sole interest being a melancholy half-built church (All Saints in Talbot Road) and a lonely public house (the Elgin). According to the paper, a number of ‘low Irish’ had settled nearby and there had been ‘a plentiful crop of Romish conversions there’. The buildings were said to have been modelled on the Poor Clares Convent in Bruges, which Manning had visited. They were austere and were grouped round a cloistered central courtyard and flanked by walled gardens. The Bruges convent also supplied the first nuns.

The Poor Clares are a closed or contemplative order of nuns, associated with the Franciscans (they were founded by St Clare of Assisi, a follower of St Francis, in 1253; the first Poor Clares convent in England was established in Newcastle in 1286). The nuns (of which there are still some 20,000 in the world today) spend much of the day in prayer and in silence, avoiding contact with the outside world. In order to serve the local Catholic population, therefore, the convent had two chapels, one for the nuns and another for outsiders coming to Mass. The altars of the chapels were built back to back, so that the movements of the celebrant’s hands during Mass were visible to both the nuns and the visitors (a bit like an old two-sided bar in a pub).

The convent remained there until 1970 until the nuns moved to a modern convent in Barnet, where they still are. The buildings were demolished, along with a terrace of Victorian houses beside the convent in Blenheim Crescent, and the whole block was transformed into the Council flats and community facilities that are there today, one of the great 1970s building projects of the Royal Borough.

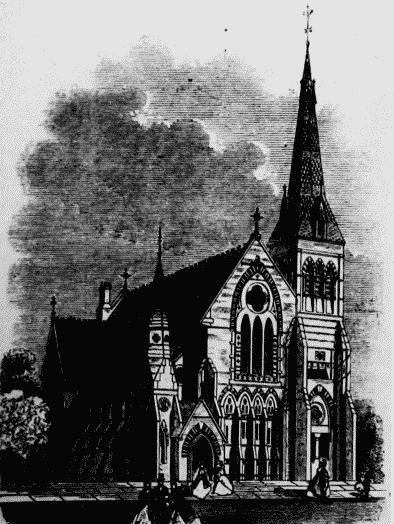

St Mark’s Church

Design for St Mark’s Church

Another ecclesiastical building that was demolished at around the same time was St Mark’s Church in St Mark’s Road. In the 1860s, the speculator Charles Blake, who was responsible for the development of a large part of the northern section of the Ladbroke estate, felt flush enough to donate a site in what is now St Mark’s Road to the Church Commissioners. They commissioned the building of a large church in highest Victorian gothic style, designed by E. Bassett Keeling, the architect of St George’s Church on Campden Hill. The Building News described it in 1869 as ‘an atrocious specimen of coxcombry in architecture’. According to the Survey of London, this verdict appears to have had some effect on subsequent opinion, for by the turn of the century Bassett Keeling’s design had already suffered considerable modification, and the church was by the time of its demolition only a fragment of the strange and original building which it once was. Now, its former site is occupied by Piper House, a hostel for people with learning disabilities.

Notting Hill Synagogue

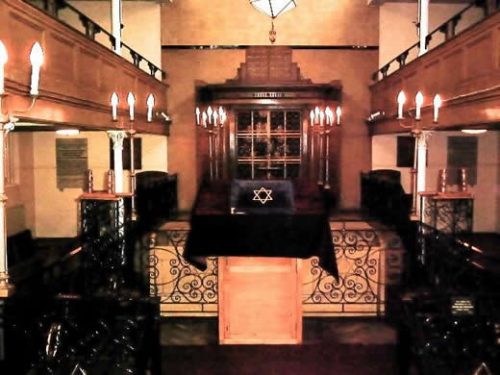

The interior of the Synagogue before it closed.

The last two decades of the 19th and the early years of the 20th centuries saw Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe on a considerable scale. Most immigrants settled in the East End, but North Kensington attracted its share, many of whom were artisans – tailors, shoemakers and stallholders.

In 1900 a Jewish congregation purchased an old church hall at Nos. 206-208 Kensington Park Road and consecrated it as a synagogue. Its raison d’ȇtre was the establishment of a less formal place of worship for the Jewish population of North Kensington than the artchitecturally – and socially – more imposing New West End Synagogue in St Petersburgh Place, Baywater. In 1905 it had a congregation of nearly 300.

So unassuming was the building in the street terrace that few Kensington residents were aware of its existence. However, as can be seen from the photograph below, the interior was beautifully proportioned, restrained and elegant in its religious detail and possessed an exceptionally calm and welcoming atmosphere.

The synagogue lived through some bad times. The building was damaged by a German bomb during the Second World War and had to be restored and reconstructed. At the time of the Notting Hill race riots, when the fascist Oswald Mosley stood for election in North Kensington, his Union Movement provocatively set up its office close to the synagogue and on 31 January 1959 one of his more rabid followers daubed three large swastikas on the building, together with the words “Juden raus” (the Nazi “Jews out” sign). The synagogue survived, however, and continued operating until the beginning of the 21st century, when a falling congregation meant that it was no longer viable. It was hoped that an organisation or group would emerge who would be able to use this important local building for a wider community use. But sadly it was not to be. The building was acquired by a commercial developer and turned over to business use.

With thanks to Peter Mishcon. This account is based on articles that appeared in our newsletter, Ladbroke News, in 2001, 2003 and 2013.

The synagogue before its closure.

The synagogue building in 2013 with the stars of David in the windows blanked out

Photographs of other churches

The synagogue building in 2013 with the stars of David in the windows blanked out

The synagogue building in 2013 with the stars of David in the windows blanked out

Page last updated 25.3.2019